Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Only one who knows the disastrous effects of a long war can realize the supreme importance of rapidity in bringing it to a close.

Sun Tzu

A SIMPLE GOLDEN CROWN lay in a glass case on the marble mantelpiece in the inner office of the Afghan president, next to a gold medallion. President Ashraf Ghani gestured to these relics of a ruler of Afghanistans past, one of the successors of Alexander. Ghani saw himself in a line with the ancient kings and borrowed these symbols of power from the national museum. It was part of his vision of destiny. On his way to file his nomination papers when running for president in 2014, he had sought a blessing from Sibghatullah Mojaddedi, the last representative of a clan who were the kingmakers in Afghanistans past.

In 1996, when I first entered the Arg, the presidential palace and seat of Afghan power, I had come in with the Taliban. A Taliban tank, festooned with garish plastic decorations from the shops on Wedding Street nearby, smashed through the gates. Fighters wandered in and out of the Arg buildings through broken windows and sat in groups on the large lawns eating pomegranates, littering the ground with red-juiced rind. When the Taliban took the capital, two years after emerging out of the desert near Kandahar, my TV crew were the only foreign journalists reporting from their front line. The ruthless speed of the assault surprised their enemies, and when they broke through the defenses of the Sarobi Gorge to the east, thought to be impregnable, the city lay at their feet. These singular fundamentalists were opposed to any depictions of men or animals, and by dawn, they had cut the heads off stone statues of dogs on either side of the staircase in the palace and shot out the faces of men in paintings on the wall.

On one side of the staircase, the walls of a bathroom were covered in blood, where the Taliban had killed the former president Najibullah and his brother overnight. Their castrated bodies hung from a nearby traffic control point on a roundabout, with cigarettes and dollar bills shoved into their hands and mouthssymbols of depravity. Hundreds of Taliban fighters stood around, watching quietly in the dawn.

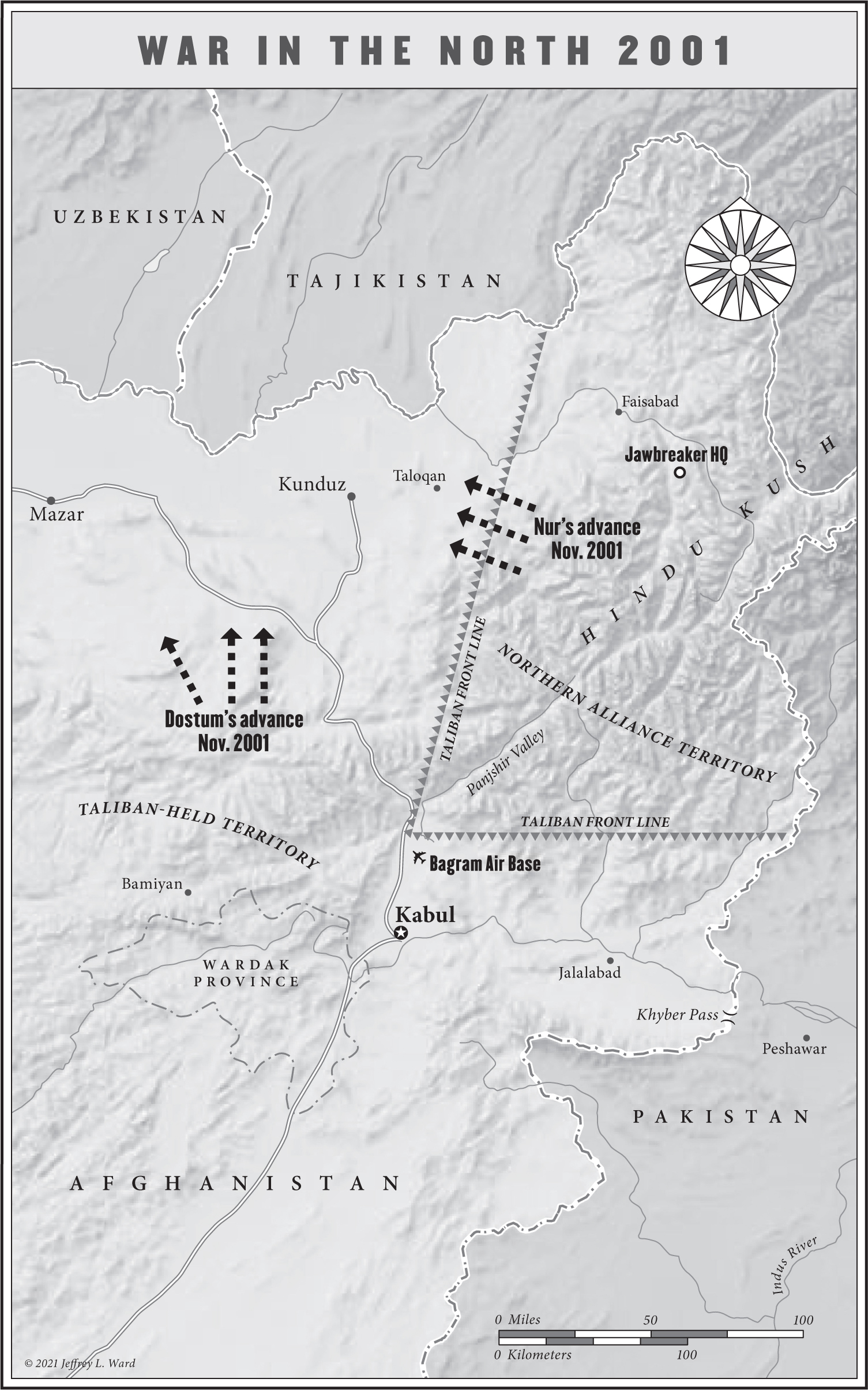

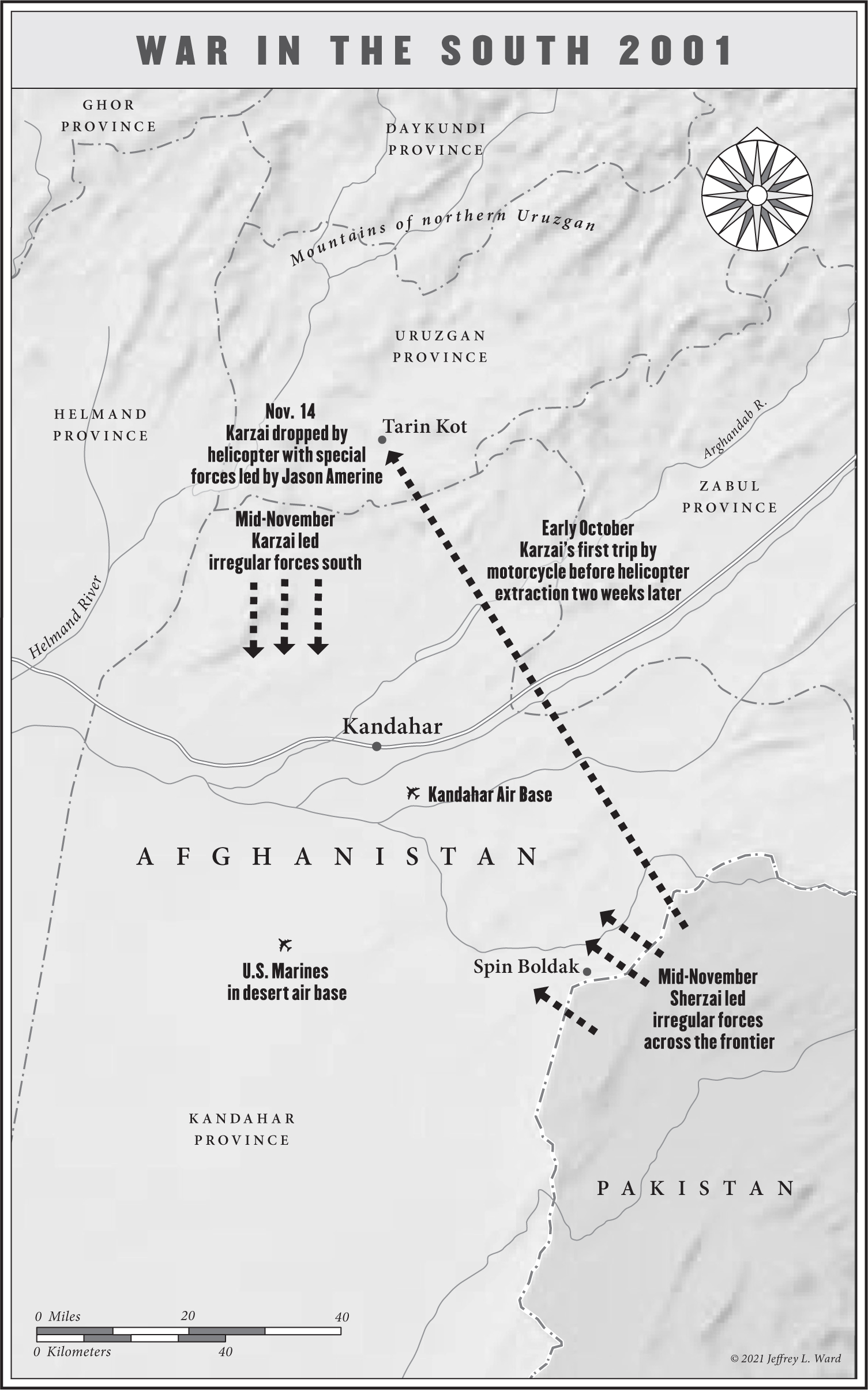

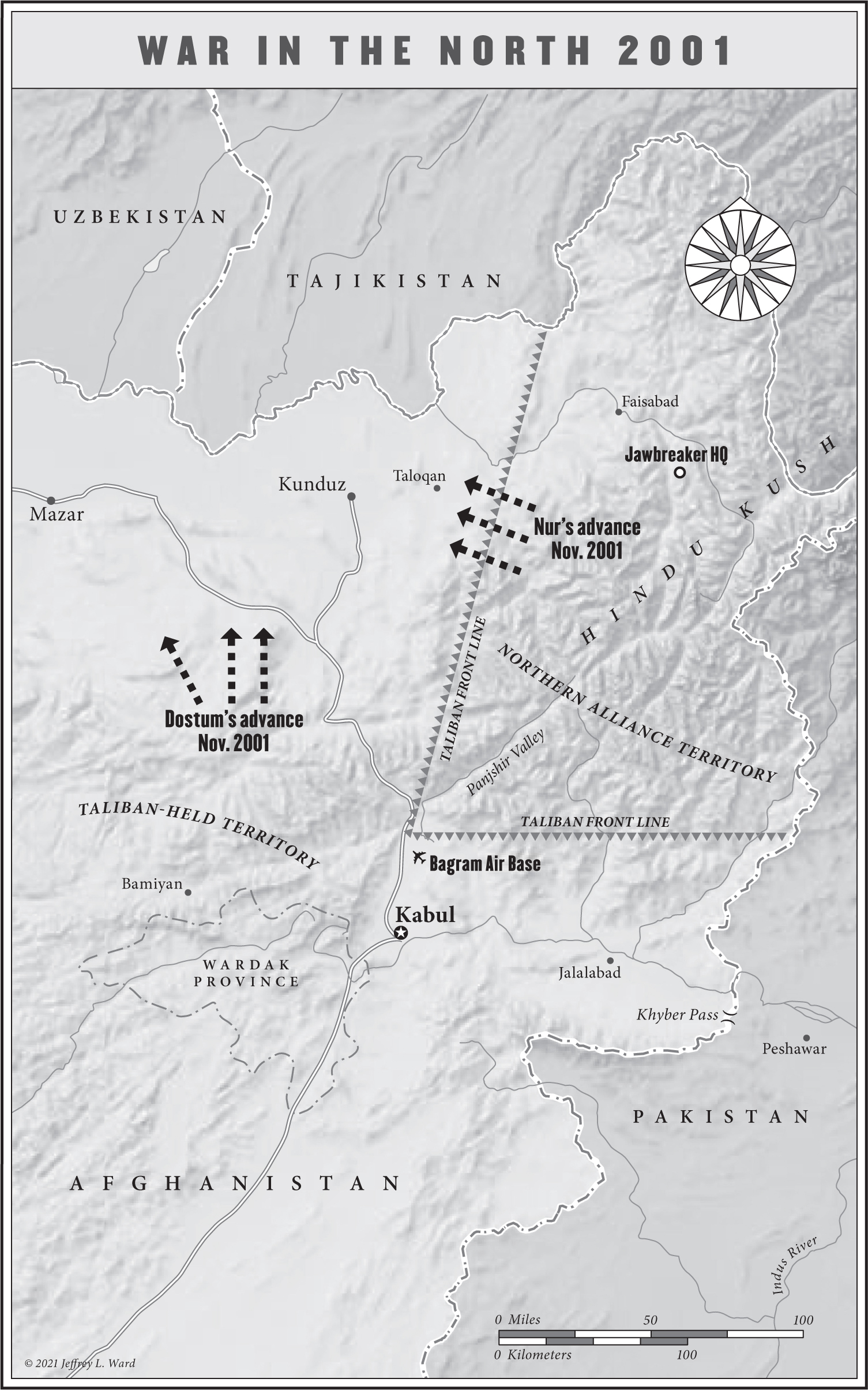

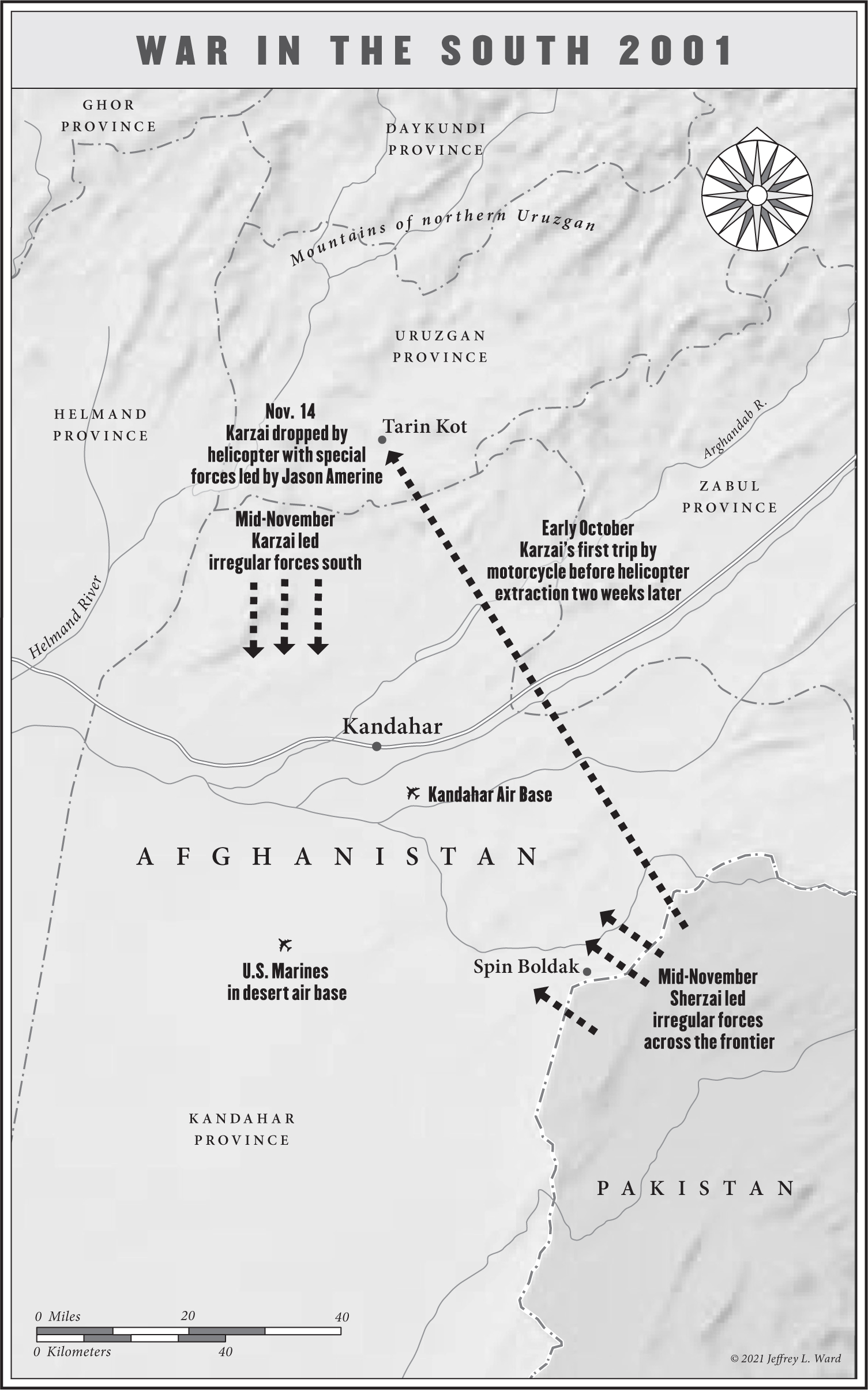

In 2001, the Taliban were in their turn quickly swept aside in a war from the air with just a handful of mostly American special operators on the ground standing up local militias. What began as an act of righteous revenge for harboring the 9/11 planners turned into Americas longest war. Twenty years on, more than a trillion dollars spent, and many lives lost, this book asks why it was so hard.

At the peak, there were 150,000 troops from more than fifty nations under the umbrella of NATO. Those who commanded this first out of area campaign for an alliance originally conceived to keep the peace in Europe had a unique task, because of the nature of the conflict and the challenges of alliance warfare. Keeping the coalition together when the predicted peacekeeping and reconstruction mission turned out to be something very different called on unusual skill. The lessons in leadership they learned have an importance beyond the military.

Commanding in Afghanistan raised questions about the ideal division between politicians and the military envisaged by Samuel Huntington in The Soldier and Statewhere politicians decide policy and the military execute it as independently as possible. The demands of the job made this difficult, wrote General Stanley A. McChrystal. The process of formulating, negotiating, articulating, and then prosecuting even a largely military campaign involved politics at multiple levels that were impossible to ignore. They had to deal with a fractious and unpredictable host, an ill-equipped coalition, nervous of the worsening conflict, and in Pakistan, a neighbor who proved a duplicitous and dangerous ally. And they were making up a new way of fighting counterinsurgency warfare in the glare of the media. McChrystal and his predecessor as commander, General David McKiernan, would be replaced by President Obamathe first field commanders to be fired since MacArthur in Korea in 1951.

Under Ghani, the traffic control point where Najibullahs body had been displayed was no longer needed. No traffic was allowed near the Arg. A bustling street market had gone, and that roundabout was well inside a new high-security zone behind blast walls. Since 2001, millions of dollars were spent renovating the eighty-acre Arg compound. Scent from a rose garden fills the air where Taliban fighters once sprawled in the dust. But the security threats meant that Ghani lived in isolation, with little contact to the country beyond the manicured lawns of his huge compound. I worked in his office in 2017 and 2018 as a communications adviser and suggested he see a daily news digest, with polling showing his popularity, but did not succeed. He had to fight isolation from reality, living and traveling in a security bubble, the only media in attendance coming from his team in the Arg.

I knew Ghani well before coming to work in his office. He was the countrys first finance minister after the Taliban, but soon fell out with the first president, Hamid Karzai, and as a BBC reporter, I interviewed him several times in the years that followed, when he was a strong critic of the international aid effort, and worked as a consultant for several other governments, putting his thinking into a bookFixing Failed States. In office, he consciously saw his administration as completing the reforms begun by King Amanullah, cut short in a coup in 1929 in which rural tribes rose up to oppose their Westernizing progressive king. As part of the renovations Ghani ordered when he took over, he found the desk made for Amanullah, had it restored, and worked at it daily. To him, it was as important a symbol as the Resolute desk in the White House.

Amanullah was lucky to escape with his life. All but one of his successors in the twentieth century were murdered in the Arg. Ghanis election saw the first democratic handover in Afghan history. Facing formidable challenges, he found it hard to fix his own failed state. He trusted very few people, and some he did trust exploited their access in their own interests. Far too much government effort was absorbed in bitter infighting over influence and resources, in a country where control of personnel brings power through patronage networks. Senior government roles come with