Table of Contents

THE LEDGER

DAVID KILCULLEN

GREG MILLS

Foreword by Rory Stewart

The Ledger

Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA

David Kilcullen and Greg Mills, 2021

Foreword Rory Stewart, 2021

All rights reserved.

Printed in Scotland

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

The right of David Kilcullen, Greg Mills and Rory Stewart to be identified as the authors of this publication is asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787386952

www.hurstpublishers.com

Every age has its follies; perhaps the folly of our age could be defined as an unmatched ambition to change the world, without even bothering to study it in detail and understand it first.

Antonio Giustozzi, Decoding the New Taliban:

Insights from the Afghan Field

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Rory Stewart

In July 2021, with the US troops almost entirely withdrawn and the Taliban beginning their advance on Kabul, Greg Mills was in the presidential palace with President Ashraf Ghani. His presence thereat a time when few other internationals were prepared to even visit the countryis a powerful illustration of the character of this man and the nature of this book, which reflects, on his partand on the part of the equally remarkable David Kilcullentheir direct and intimate engagement with Afghanistan over sixteen years.

Kilcullen and Mills are pragmatic optimists. They refuse to accept easy solutions, but they also reject easy pessimism. They are unrelenting in their criticisms. But they remain convinced that nothing was preordained, that Afghanistan was never condemnedby its history, or structures or context to failure. And this refusal to patronise, or dismiss Afghans or Afghanistan, reflects both the authors hard-won arguments, deep experience and reflection, and their direct involvement in a prodigious range of levels of this intervention. Kilcullen and Mills were at the heart of the policy machine, serving as the closest advisors to the most senior generals on the ground (and in Kilcullens case, as senior counterterrorism advisor to US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice). But they also developed friendships with police officers at border posts, with security teams in the capital, and with business people struggling in industrial parks on the edge of Kandahar. Their irrepressible curiosity drove them to ride in Pakistani trucks at six miles an hour along some of the most dangerous roads in Afghanistan simply to try to understand the way the road taxation system functions, and focus on the electricity supply for cold storage systems.

What makes the book unique, however, is the experience they bring from outside Afghanistanwhether that is David Kilcullen starting as a young Australian infantry captain in a village in west Java or his distinguished service in the Middle East, and Latin America, or Greg Millss work as an advisor to the heads of state in Nigeria, Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. And they have a fine eye for historical detail (whether it is LBJ saying I feel like a jackass caught in a Texas hailstorm. I cant run, I cant hide and I cant make it stop, or French President Charles de Gaulle warning Kennedy in 1962 that I predict you will, step by step, be sucked into a bottomless military and political quagmire).

So this is a book not only about Afghanistan but also about Vietnam, Mali and Somaliland. And this range of lessons gives them a uniquely confident and broad sense of the failures of international development projects, and an argument for what workswhat can be done effectively in places like Somaliland if there is genuine local ownership and leadership, even in the most impossibly testing conditions. These arguments reflect experience, scepticism and faith.

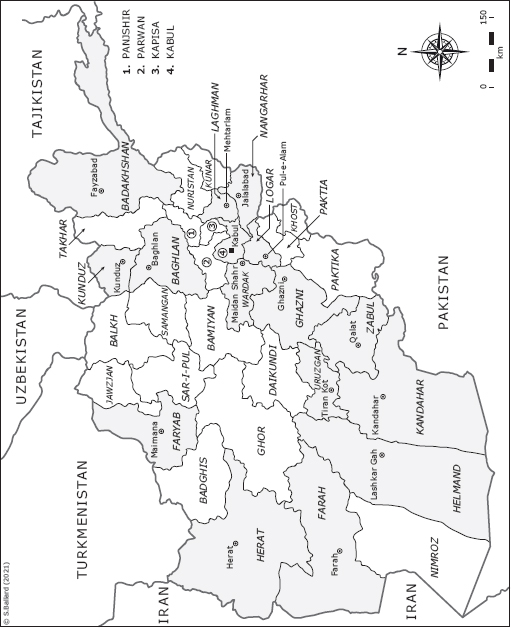

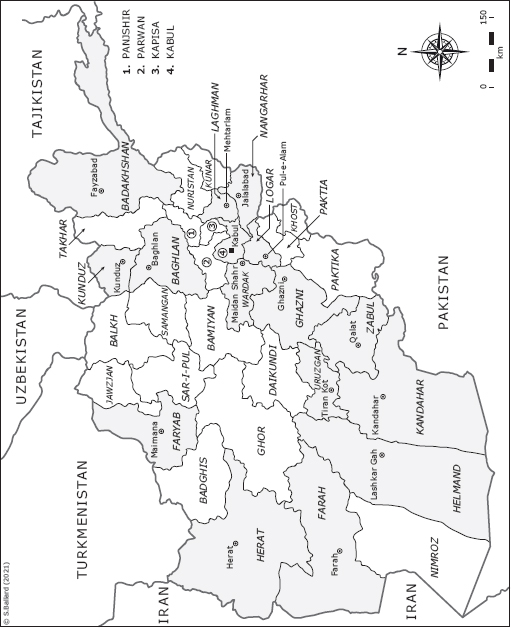

Nothing shows their strengths better than their superbly detailed reporting on the last phase of Afghanistan, and the way in which the Taliban took over the country. No one has written as well about how each Taliban campaign over the final five yearsincluding paradoxically their apparent lossesput them in a stronger position. Kilcullen and Mills are able to explain (and in painful detail) how the increasing focus on special forces undermined the capacity of the Afghan national army and removed some of the most capable soldiers; how as the helicopters were grounded, it became impossible to supply ammunition, food or water to Afghan forward operating bases; how those basesstarved, unpaid in the midst of a population that had lost the faith to cooperatefound themselves encircled, and ultimately saw no alternative other than to walk out. And how the fall of each base, encouraged the fall of its neighbour. They illustrate how the final deployments in Kandahar and Lashkar Gah undermined the capacity to fight in Kabul; and how Ashraf Ghanis relationship with the former Jihadi commanders fundamentally crippled the ability to supplement the army with a militia response.

All of this is told with immense elegance, empathy, respect for Afghans, and deep understanding of the local terrain and context. Kilcullen and Mills explain something that is otherwise very difficult to understand: how a comparatively small Taliban force was able to achieve such a stunning and rapid victory over a large conventional army. And in doing so, they suggest much broader lessons. (They suggest for example the dynamics which might explain how comparatively small attacking forces along the Danube in the late fourth century and early fifth century were able to ultimately undermine and destroy the far larger, and apparently far better resourced, Roman Empire.)

The central question, however, which this book poses again and again, is why highly intelligent and highly experienced people were able to make such catastrophic errors. Mills and Kilcullen observe that any visitor to Afghanistan during the war, and anyone (including both of us) who served as a military or civilian adviser in the field during the conflict, could not fail to be struck by the extraordinary commitment and competence of military commanders. The civilian leadership was also frequently far better informed, far more thoughtful, and intelligent, than critics acknowledge. And yet, as Mills and Kilcullen point out, they got so much wrong. They did not try to reach a political settlement with the Taliban in 2001and had they done so then at a time of maximum leverage, the current debacle might have been avoided. International strategy and policies lurched in hectic inconsistency between the narrowest objectives of counter-terrorism, to the grandest dreams of national transformation. NATO built a grotesquely unsustainable Afghan military, which patently could not survive without foreign support, despite knowing that they would withdraw their support. US generals insisted on the importance of local ownership, while deploying 130,000 foreign troops, and side-lining Afghan presidents and firing Afghan governors. Above all the international community consistently and repeatedly tried to do things which they could not do. The very mission statements around which the military and civilian strategies for state-building and counter-insurgency were every organised (the idea of nation-building under fire) were aspirations to do what was almost certainly impossible. And this should have been obvious even at the time.