Contents

Page-list

Guide

ALSO BY JOSEPH J. ELLIS

American Dialogue: The Founders and Us

The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 17831789

Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence

First Family: Abigail and John Adams

American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic

His Excellency: George Washington

Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation

American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson

Passionate Sage: The Character and Legacy of John Adams

After the Revolution: Profiles of Early American Culture

School for Soldiers: West Point and the Profession of Arms (with Robert Moore)

The New England Mind in Transition

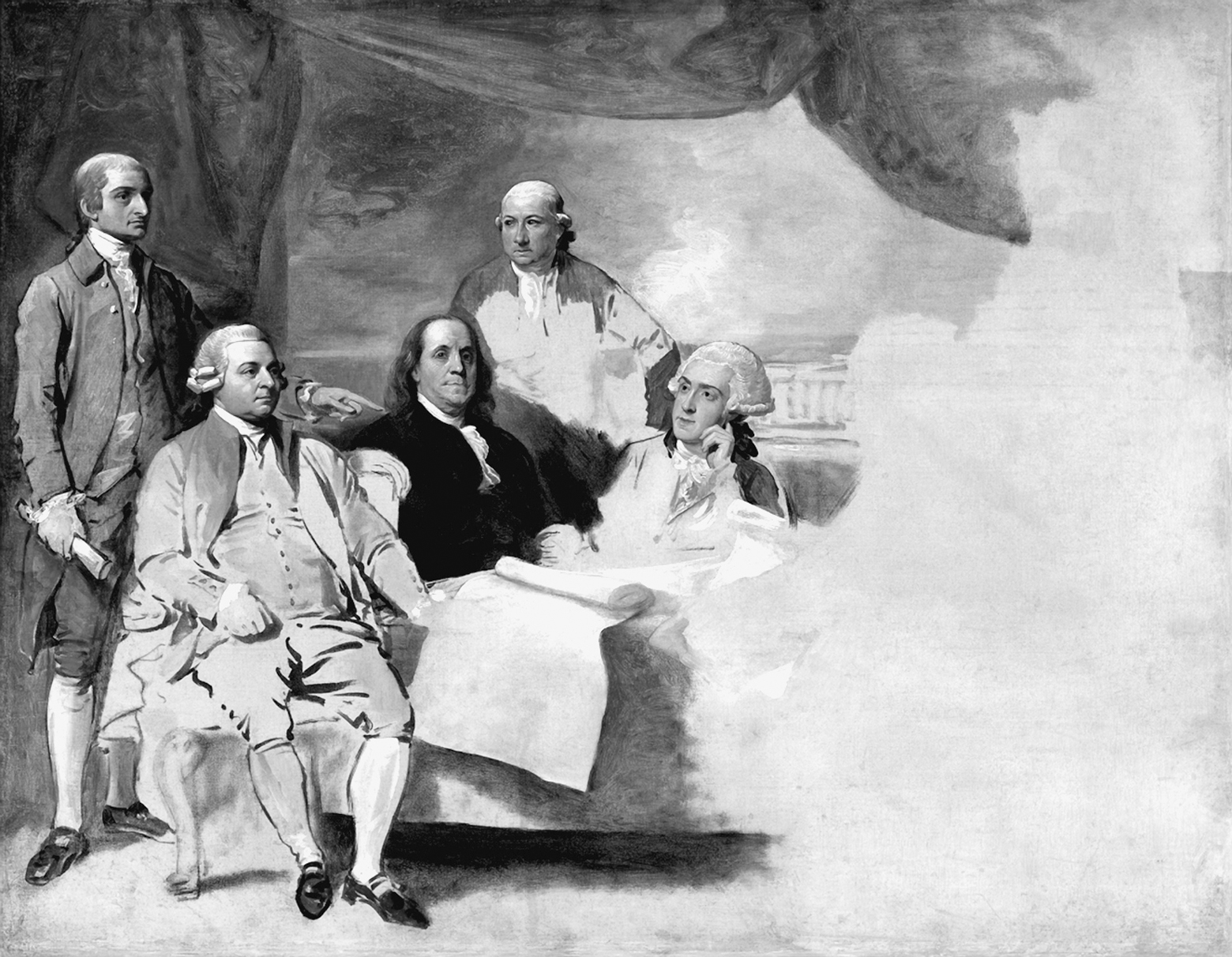

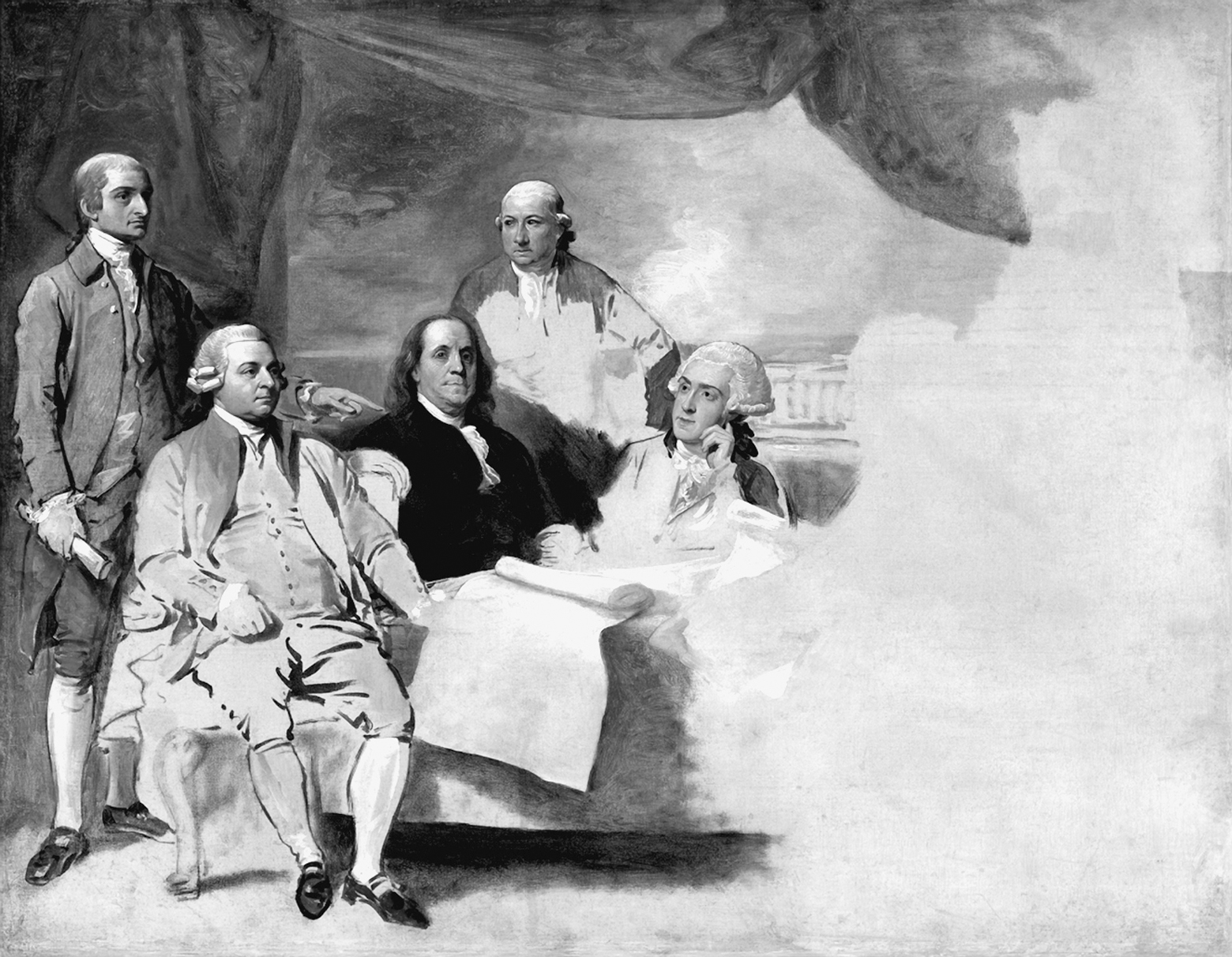

This Benjamin West portrait of the men who negotiated the Treaty of Paris remains unfinished because the British diplomatic team refused to pose. Left to right, they are John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin, Bens grandson.

THE CAUSE

The American Revolution

and Its Discontents,

17731783

JOSEPH J. ELLIS

Copyright 2021 by Joseph J. Ellis

All rights reserved

First Edition

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design by David Gee

Front jackt art: (rifles) Everett Collection / Shutterstock; Stocksnapper /

Shutterstock; (lithograph) Washington at Princeton, Jan. 3, 1777, by D. McLellan,

1853, National Archives (148-GW-331); (Great Fire of New York, 1776) Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Back jacket art: pavelmidi / Depositphotos Inc.

Book design by Ellen Cipriano

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Ellis, Joseph J., author.

Title: The cause : the American Revolution and its discontents, 17731783 / Joseph J. Ellis.

Other titles: American Revolution and its discontents, 17731783

Description: First edition. | New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021028335 | ISBN 9781631498985 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781631498992 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783. | United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Causes. | Great BritainColoniesAmericaHistory18th century. | United StatesPolitics and governmentTo 1775. | United StatesPolitics and government17751783.

Classification: LCC E210 .E45 2021 | DDC 973.3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021028335

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

In memory of William S. McFeely, who lived a full life, sharing with readers and students his contagious enthusiasm for the promises and pitfalls of American history.

CONTENTS

I do not mean to say, that the scenes of the revolution are now or ever will be entirely forgotten; but that like every thing else, they must fade upon the memory of the world, and grow more and more dim by the lapse of time.

Abraham Lincoln, Lyceum Address, January 27, 1838

Real historical understanding is not achieved by the subordination of the past to the present, but rather by... attempting to see life with the eyes of another century than our own.

Herbert Butterfield, The Whig Interpretation of History (1931)

T he pages that follow represent my attempt to tell the story of a highly compressed historical moment that subsequent generations called the American Revolution. No one called it that at the time. The British called it the American rebellion, an accurate description of the eight-year war fought by former British colonists who sought to secede from the British Empire. These former colonists did not regard themselves as Americans, but rather as New Englanders, Virginians, or Pennsylvanians. No such thing as an American national identity yet existed. The term they used to describe their war for independence was The Cause, a conveniently ambiguous label that provided a verbal canopy under which a diverse variety of political and regional persuasions could coexist, then change shape or coloration when history threw choices at them for which they were unprepared. Thus my title.

Whether The Cause was truly a revolution remains, over two hundred years later, a controversial question. My former mentor, Edmund S. Morgan, liked to resolve the debate with a wink, defining a revolution as a sudden change in human affairs so traumatic that no one understood it, either at the time of its happening or thereafter. No less an authority than George Washington observed at the end that any historian who managed to write an accurate account of the war for independence would be accused of writing fiction.

The earliest and most articulate advocates of The Cause insisted that they were not proposing a revolution. Quite the contrary, it was the British government that was attempting to impose a revolutionary change in the structure of the British Empire by insisting that Parliament was empowered to tax and legislate for the colonies without their consent. They opposed that change because it violated their historic rights as Englishmen, hardly a revolutionary agenda. Moreover, when some of the most ardent champions of The Cause embraced the radical implications of its meaningthe end of the property qualification to vote, the expansion of womens rights, a gradual emancipation program to end slaverya chorus of voices, led by John Adams, insisted that such drastic changes must be deferred.

We can, and should, argue about the wisdom of that deferral strategy. There will be those who embrace the conviction that justice delayed is justice denied. But they must contend with the inconvenient truth that any attempt to implement the full meaning of The Cause would have undermined the unity necessary to win the war and thereby rendered American independence impossible. In her On Revolution, Hannah Arendt has called attention to the irony of it all. The French Revolution is admired for attempting to implement its radical agenda all at once and failing. The war for American independence is criticized for deferring its full promise and succeeding.

Wherever one chooses to take a stand, there can be no question that we must come to terms with an unusual kind of political animal, the prudent revolutionary. In several senses, their prudence proved wise, in fact brilliant. But, as we shall see, when it came to slavery, the outcome was tragic, and we are still living with the residue of that failure.