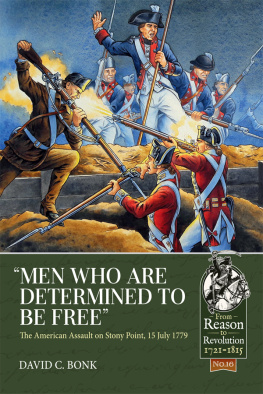

Men who are Determined to be Free

The American Assault on Stony Point, 15 July 1779

David C. Bonk

Helion & Company Limited

Unit 8 Amherst Business Centre

Budbrooke Road

Warwick

CV34 5WE

England

Tel. 01926 499 619

Fax 0121 711 4075

Email:

Website: www.helion.co.uk

Twitter: @helionbooks

Visit our blog at http://blog.helion.co.uk/

Published by Helion & Company 2018

Designed and typeset by Farr Out Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Cover designed by Paul Hewitt, Battlefield Design (www.battlefield-design.co.uk)

Text David C. Bonk 2018

Original artwork by Ed Dovey, Helion & Company 2018; other images as credited

Maps drawn by George Anderson Helion & Company 2018

Cover: The Assault on the Upper Works at Stony Point by Ed Dovey, Helion & Company 2018

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The author and publisher apologise for any errors or omissions in this work, and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

ISBN 978-1-912174-84-3

eISBN 978-1-912174-84-3

Mobi ISBN 978-1-913118-08-2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of Helion & Company Limited.

For details of other military history titles published by Helion & Company Limited, contact the above address, or visit our website: http://www.helion.co.uk

We always welcome receiving book proposals from prospective authors.

Contents

Introduction

The Hudson Highlands loom large in the history of the American Revolution. Both American commander George Washington and British commander Sir Henry Clinton recognized early in the struggle that the Hudson River and the surrounding hills and valleys represented a natural barrier to movement between New England and the Middle Colonies. The rugged landscape and limited crossings of the Hudson River made campaigning in the region challenging. For the Americans, control of the Hudson River crossings would ensure the uninterrupted flow of men and supplies from New England into the seat of war in Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey. For the British, isolating the New England colonies from the rest of the lower colonies would have significant strategic benefits, denying the Continental Army critical resources. In addition, control of the Hudson Highlands would expedite communication with British forces in Canada and threaten the strategic center of Albany.

The clash at Stony Point in 1779 was the last episode in struggle for supremacy in the Hudson Highlands, and its capture by Waynes light infantry represented a signal victory for Washington and the Continental cause in a year characterized by frustrating maneuvering for strategic advantage by both sides.

The assault on Stony Point reflected the personalities and experiences of the principle antagonists: Sir Henry Clinton; George Washington; and Brigadier General Anthony Wayne. Clinton returned to the Hudson Highlands in May 1779 out of a state of exasperation with the overall stalemate which had characterized the war since the British had evacuated Philadelphia in June 1778. Despite assurances given by the British government that he would have freedom of action upon replacing Sir William Howe as Commander-in-Chief of the British armies in American in June 1778, Clinton continued to be burdened with interference by Lord George Germain, Secretary of State for America, and others in the British government. Attempting to manage a war over 3,500 miles of ocean through directives written three to four months earlier was an open invitation for misunderstandings and missed opportunities. Promised British reinforcements, intended to support these strategic directives, were either delayed or redirected to other theaters at the same time as portions of Clintons command were ordered away from New York. Faced with dwindling resources and orders to shift the locus of the war to the southern Colonies, Clinton was anxious to bring Washington and the Continental Army into a decisive showdown.

Understanding the importance of the Hudson Highlands to the American cause, Clinton gambled that Washington could not allow the British to threaten the complex of fortifications at West Point and disrupt the flow of supplies and reinforcements from New England. Clinton was no stranger to the Highlands, having successfully advanced north towards Albany in October 1777, capturing Forts Montgomery and Clinton along the way in a failed attempt to reach Lieutenant General John Burgoynes doomed column.

Clinton was correct in his assessment that Washington feared the loss of the West Point forts and the Highlands. Yet as much as West Point meant to the American cause, Washington also had a clearheaded understanding that the survival of the Continental Army trumped all other considerations. Throughout the war Washington exhibited a reticence to commit his army on terms he found to his disadvantage but at times exhibited flashes of a more aggressive spirit. This aggressive trait revealed itself throughout the course of the war and was typically tempered by the more cautious attitudes of members of his general staff. Washingtons decision to attack Stony Point, in the face of widespread skepticism from his staff, was born of that spirit.

Washington found in Brigadier General Anthony Wayne a kindred spirit. Although Wayne had at times fallen into line with his fellow generals to support a more conservative approach, more often Washington had Waynes support for more aggressive actions. Like Clinton, Wayne, in command of the American assault on Stony Point, would craft plans reflecting his own experience. Only two years earlier in September, 1777 Wayne had watched helplessly as his Pennsylvania division suffered through the trauma of a British night assault on his camp at Paoli. From that night at Paoli Wayne understood risks and rewards associated with the plan to attack Stony Point. Washington, Clinton, and Wayne would carry these experiences with them into the Hudson Highlands in 1779.

Stalemate, 1779

1779 began with high expectations for both American and British armies, which stood like two bloodied boxers responding to the bell to begin the next round, well into their fight, warily eyeing their opponents, both staggered from previous blows, both circling their opponents, waiting for an opportunity to strike.

General George Washington, Detroit Publishing Co., 1900 (Library of Congress).

In late December, 1778 American commander-in-chief George Washington was called to Philadelphia to discuss strategy for the coming year with members of a special Committee of Conference appointed from the Continental Congress. Although he entered the city on 22 December, Washingtons arrival was formally announced to the general public on Christmas Eve when the Pennsylvania Packet published the announcement;

On Tuesday last arrived here, George Washington, esquire, Commander in Chief of the Armies of the United States. Too great for pomp and as if fond of the plain and respectable rank of a free and independent Citizen, His Excellency came in so late in the day as to prevent the Philadelphia Troop of Militia Light-Horse, Gentlemen, Officers of the Militia, and others of this city from shewing those marks of unfeigned regard for this GOOD and GREAT MAN.