THE ACCIDENT OF COLOR

A STORY OF RACE IN RECONSTRUCTION

DANIEL BROOK

Copyright 2019 by Daniel Brook

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Beth Steidle

ISBN 978-0-393-24744-2

ISBN 978-0-393-24745-9 (ebk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

FOR OUR REPUBLIC

CONTENTS

A Note on Language: This work contains quotations from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources. Spelling, italics, underlining, punctuation, and capitalization have been rendered in the original, even when they do not conform to contemporary norms of written American English. Offensive language in quotations has also been rendered in the original.

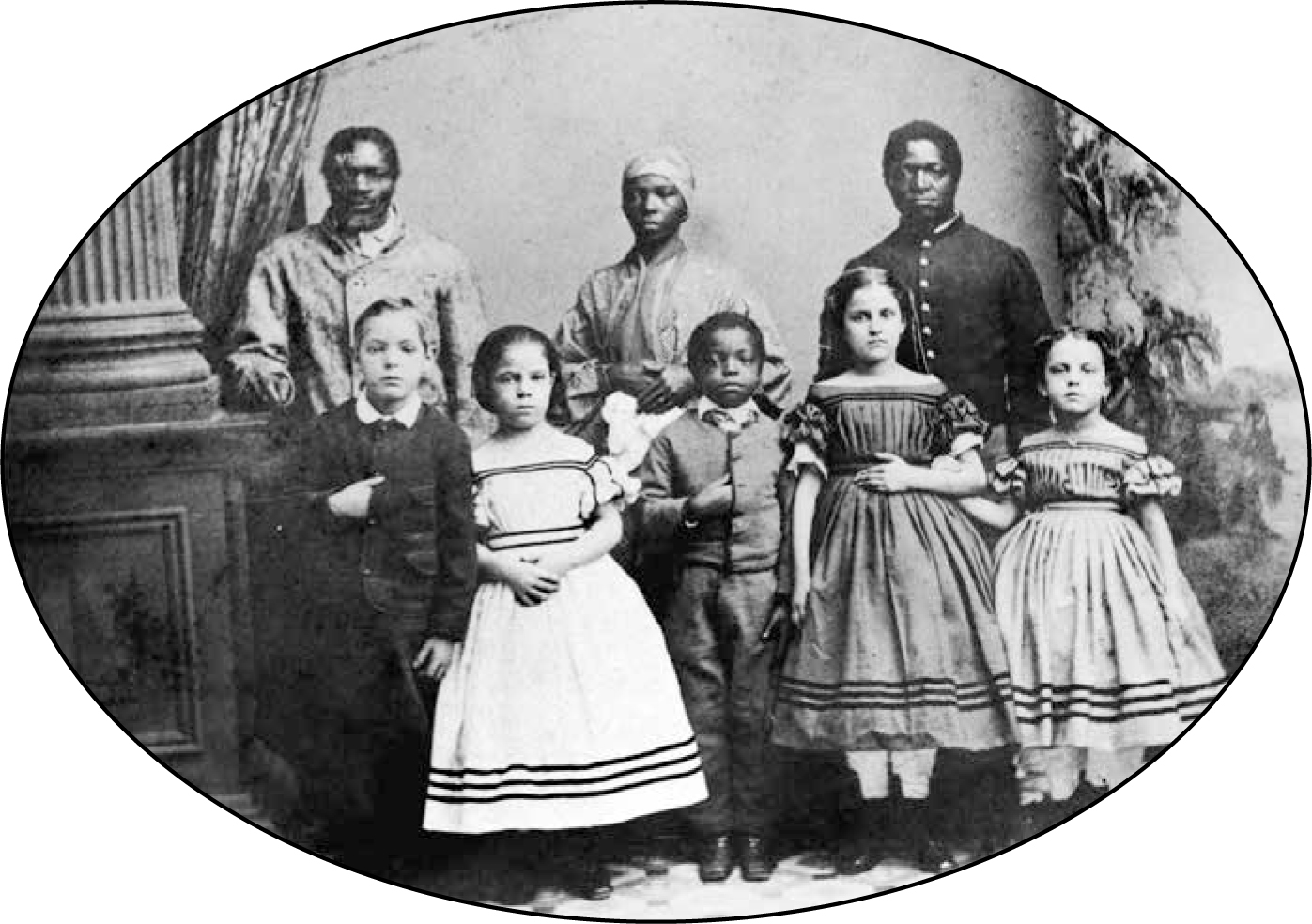

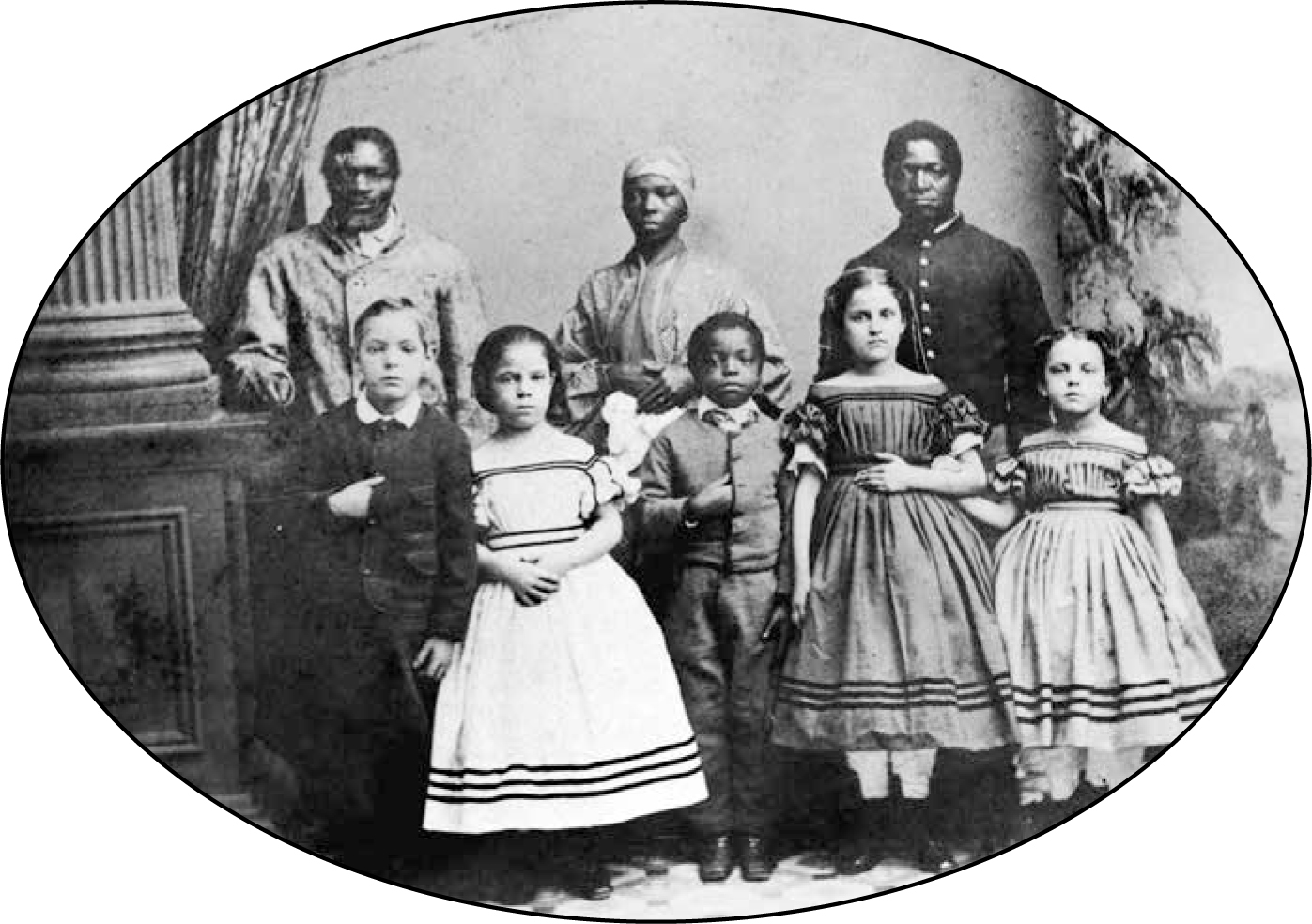

Emancipated Americans in New Orleans during the Civil War.

(Courtesy of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA)

W hen Williston Henry Lofton, a history major at Howard University, decided to earn a masters degree in tandem with his bachelors, he had all he needed except a thesis topic. Fishing around, Lofton became captivated by an odd subject: the history of the civil rights movement.

It was an unfashionable, even anachronistic, choice. The civil rights struggle of five decades past was not something most anyone was interested in. Its victories had faded and the landscape for African-Americans was bleak. In official Washington, just beyond the gates of the Howard campus, hostile forces held sway in the White House, in Congress, and on the Supreme Court. Voter suppression was rampant and police shootings of African-American youth commonplace. But as young Williston dove into the archives, he discovered remarkable material. He went on to write a fine survey of the protests, boycotts, sit-ins, test cases, and legislation of the civil rights era.

Lofton submitted his thesis in the spring of 1930 and entitled it Civil Rights of the Negro in the United States, 18651883. The monograph opened with these words: A study of the civil rights of the Negroes in the United States in the two decades following the Civil War reveals surprising information to the investigator. The surprise exists not so much in the denial of civil rights to the Negro, for that is expected, but rather in the great degree to which civil rights were accorded the Negro by both the State and the Federal governments.

In unearthing the achievements of this forgotten civil rights movement, Lofton faced twin challenges. First, he was at odds with the view of leading historians who saw the granting of civil rights to African-Americans during Reconstruction as a tragic mistake and Klan terrorism as a necessary evil in revoking those rights. Pioneered by white supremacist historians besotted with the latest racial pseudosciencemen like William A. Dunning of Columbia Universitythis view had been popularized through Thomas Dixon Jr.s pulp fiction and D. W. Griffiths subsequent blockbuster screen adaptation of it, The Birth of a Nation .

Williston Henry Lofton was also up against rampant historical document destruction; white reactionaries had covered up the most stunning achievements of the postwar integrationists. Even if the undergraduate Lofton had had the time, the funds, and the freedom to scour Southern archives for original documentationmany were held by whites-only institutions that barred researchers of colorhe would have hit numerous walls. In New Orleans, the school board records for the districts integrated period from 1870 to 1877 had long ago been expunged from the archives. At the University of South Carolina, the records of the student debating society from the schools integrated era, from 1873 to 1877, had been defaced page by page with black-ink tombstone pictographs inscribed Negro Regime. To try to fill these gaps in the primary source records, Lofton was forced to reconstruct Americas first attempt at interracial democracy as best he could through newspaper coverage of civil rights activism and court records of civil rights cases.

Facing these obstacles, even when W. E. B. Du Bois tried his hand at a history of Reconstruction, which he published in 1935, the nations preeminent African-American scholar lamented that the material today... is unfortunately difficult to find. Little effort has been made to preserve the records of Negro effort and speeches [and] actions.... The loss today is irreparable, and this present study limps and gropes in darkness.

In the depths of segregation, even with complete information, it would have been hard to properly process the antiracist activism of the Reconstruction era. Under the system known as Jim Crow, named for a minstrel shows blackface stereotype of a slave, Americans were pressed into legal categories of white and colored with rights and restrictions allocated accordingly. Jim Crows widening of whiteness, the one-drop rule of blackness, and retroactive complete conflation of blackness with servitude made it difficult to comprehend the leading Reconstruction activists on their own terms. These were men and women who defied binary racial categorizations and, indeed, fought against them. That such a disproportionate number of pioneering Reconstruction-era civil rights activists sprang from the distinctive, long free, openly biracial communities of New Orleans and Charleston is no coincidence. For generations, New Orleanss Creoles of color and Charlestons Browns had been resisting the imposition of race-based rights and challenging Americas black-or-white notion of race itself. Only in light of these communities unique histories and self-conceptions can their cities outsized civil rights achievements be understood.

Just as an historian of medieval France must keep in the front of her mind that in the Middle Ages there was no France, only a smattering of feudal lands that would one day become France, so a student of Reconstruction must be cognizant that the firm racial binary Americans accept to this day is a result of Jim Crow, not a cause of it. The one-drop rulethe concept that any trace of African ancestry at all makes an American a negrowas not even conjured until the 1850s and was not widely accepted until the early twentieth century. It is only because mixed-race activists were defeated in their valiant effort to stop a regime of race-based rights that contemporary Americans view society through the racial blinders that we do. Today, decades after the dismantling of Jim Crow, Americans still see our society and ourselves in binary terms of white and colored. That our racial system is second nature to us but incomprehensible to the rest of the worldeven to people from other New World societies that once practiced slavery but never instituted Jim Crowshould highlight for us how peculiar it is.