When America First Met China: An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail

Rebels

at Sea

PRIVATEERING

IN THE

AMERICAN

REVOLUTION

Eric Jay

Dolin

To librarians everywhere who, through hard

work and dedication, support writers, researchers,

learners, and book lovers alike. This writer

couldnt have done it without you.

CONTENTS

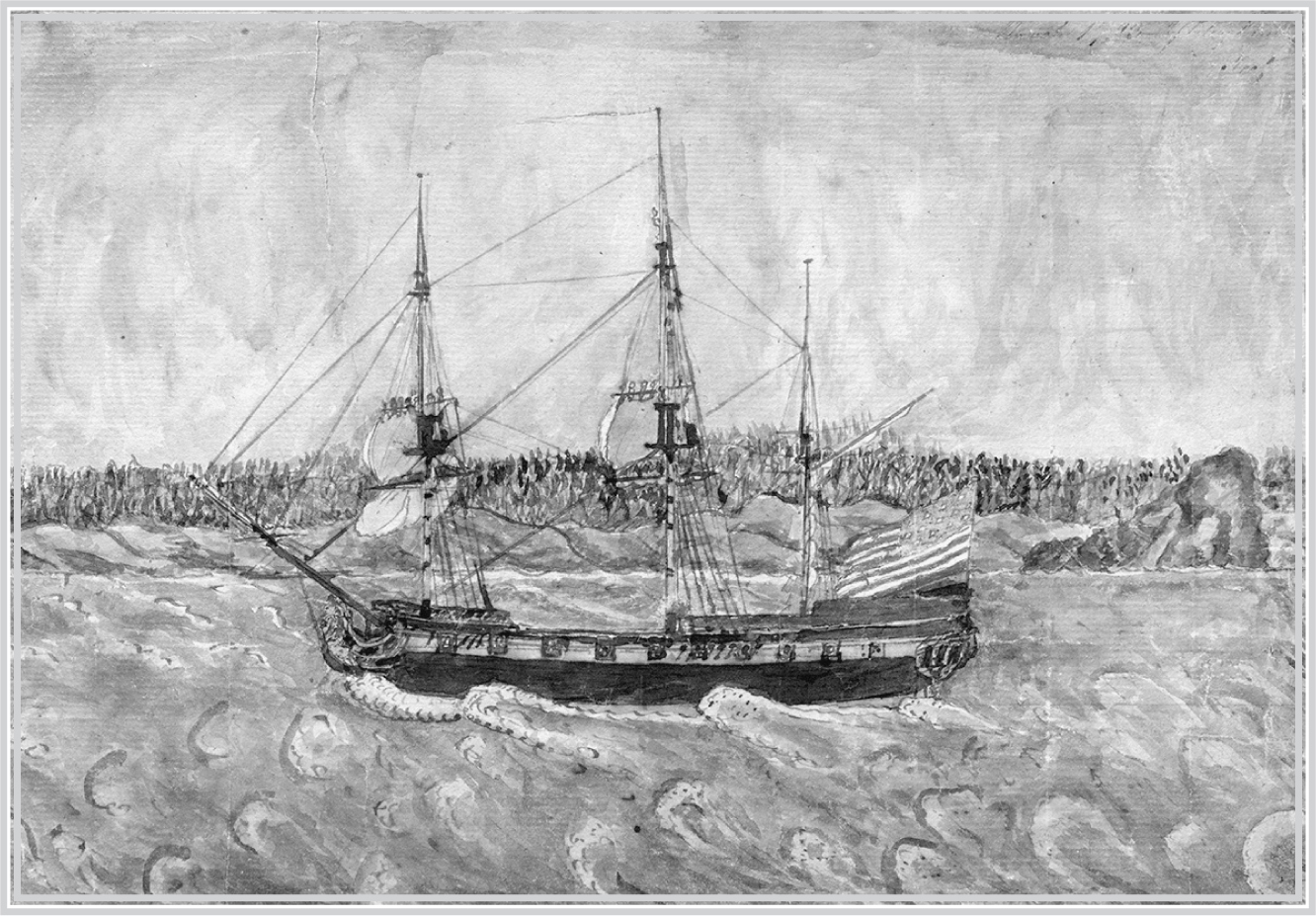

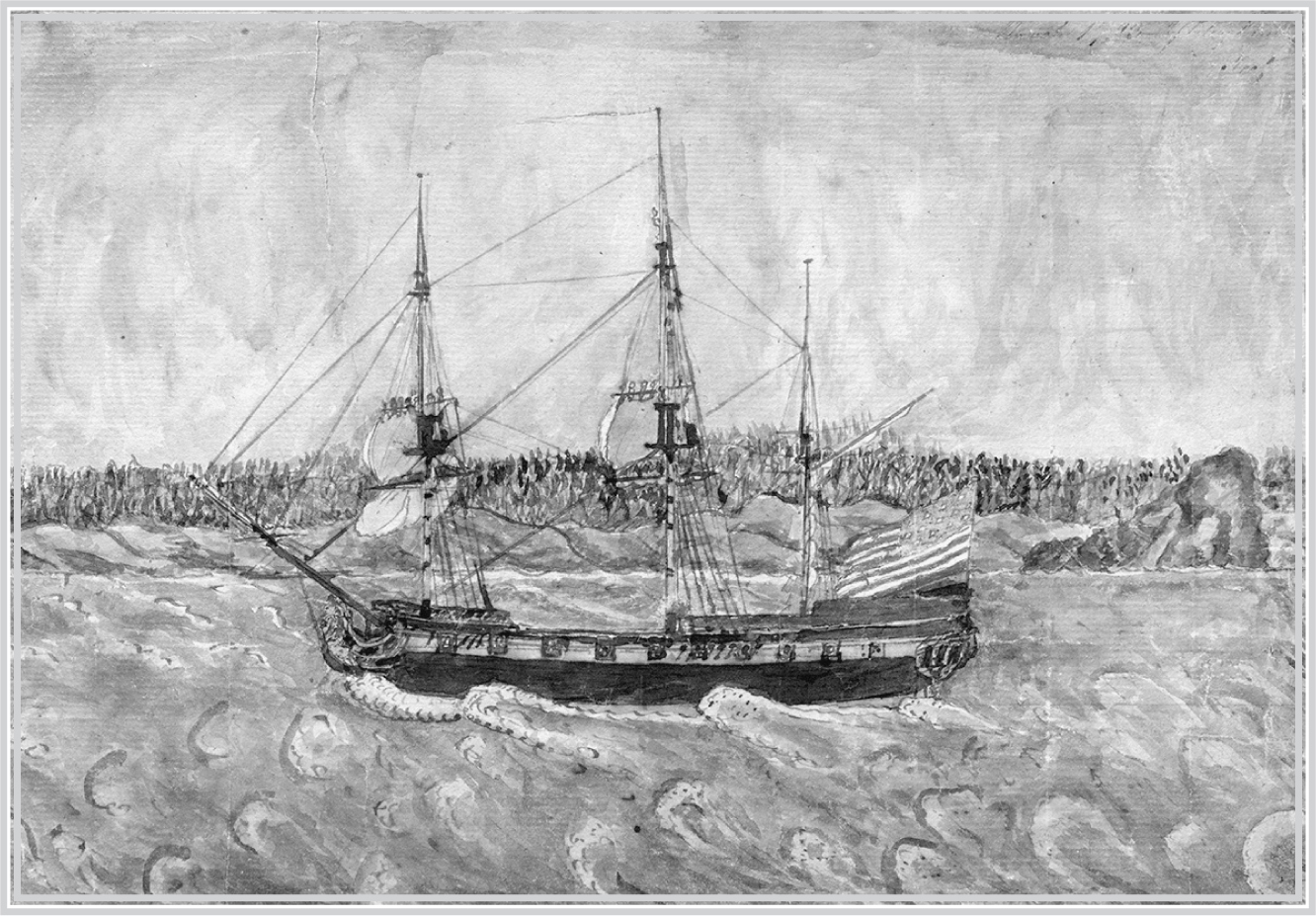

Marblehead privateer Argo , painted by Ashley Bowen, 1783.

As with many men of the time who were not from wealthy or prominent families, we know little about Haradens early life. Born in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1745, he was sent to Salem as a boy to apprentice as a cooper in the employ of Joseph Cabot, a successful merchant. Haraden must have gained some experience at sea in the years leading up to the American Revolution, because in June 1776 he was commissioned as first lieutenant on the aptly named sloop Tyrannicide , which Massachusetts sent out as part of its colonial (soon to be state) navy. The idea was to protect its merchantmen and seize British ones. As first lieutenant and later captain of the Tyrannicide , Haraden did just that, earning the respect of the Massachusetts Board of War, which called him a who always acquitted himself with spirit and honor. Disagreements over pay, however, led him to leave the Massachusetts navy and become a privateersman. On September 30, 1778, he took command of the Pickering .

The Pickering was one of more than a thousand American privateers, and Haraden was one of tens of thousands of privateersmen who served during the American Revolution. (Often both the vessels and the men who served on them are called privateers. Because that can lead to confusion, here the vessels will be referred to as privateers and the men sailing them privateersmen.) Privateers were armed vessels owned and outfitted by private individuals who had government permission to capture enemy ships in times of war. That permission came in the form of a letter of marque, a formal legal document issued by the government that gave the bearer the right to seize vessels belonging to belligerent nations and to claim those vessels and their cargoes, or prizes, as spoils of war. The proceeds from the auction of these prizes were in turn split between the men who crewed the privateers and the owners of the ship. Typically, governments used privateers to amplify their power on the seas, most notably when their navies were not large enough to effectively wage war. More specifically, by attacking the enemys maritime commerce and, when possible, its naval forces, privateers could inflict significant economic and military pain at no expense to the government that commissioned them. Privateers were like a cost-free navy. One late nineteenth-century historian dubbed them

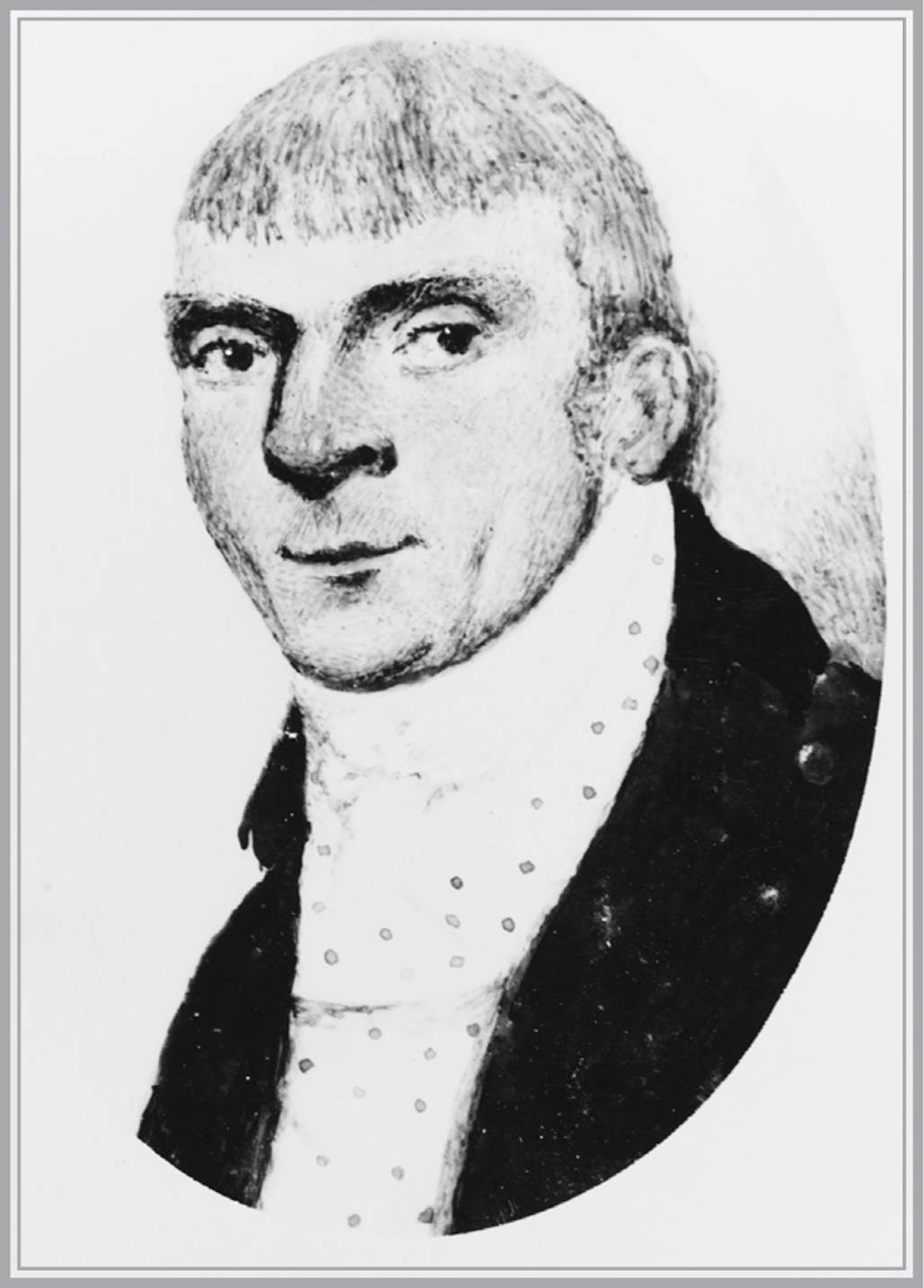

Photograph of a miniature painting of Jonathan Haraden by an unknown artist, circa late 1700searly 1800s.

There were two types of privateers. Some were heavily armed with large crews, their sole purpose to seek out and capture enemy ships. The large crew was needed to work the cannons and fight enemy sailors and marines with muskets and swords but also to man the newly acquired prizes and sail them back to portwhile allowing the privateer to continue on, now with a smaller but still sufficient crew, searching for the next prey. Other privateers were primarily merchant vessels intent on trade; these traveled between ports to buy and sell goods but also had permission to attack enemy shipping, and would do so when the opportunity arose. This latter type of privateer was often referred to as a letter of marquenot to be confused with the authority described abovewhereas the first type of privateer was called just that, a privateer. Because the letter of marques main purpose was trade, it generally had fewer cannons and a smaller crew than a conventional privateer, although it usually took along enough crewmen to man a few prizes. One other crucial difference concerned pay. While the crews of privateers earned money only if they took prizes, those on letters of marque were paid a base salary, which was supplemented by any prize money they earned. in the vast majority of the prizes during the Revolution, as compared to letters of marque. Some vessels alternated between the two statuses. The Pickering sailed variously as a privateer and a letter of marque; and it was a letter of marque on its trading voyage between Salem and Bilbao when it sighted the Achilles . (This book uses the term privateer to cover both types of vessels, except where differentiating between the two is necessary.)

As captain of the Pickering from the fall of 1778 to early 1780, Haraden took numerous prizes. , and do what was to be done in a short time.

Haradens encounter with the Achilles came at the end of a voyage that began in the spring of 1780 when the Pickering , loaded with West Indian sugar, sailed for Bilbao. Upon entering the Bay of Biscay on June 1, Haraden spied a British privateer named the Golden Eagle , which had a crew of fifty-seven and twenty-two cannons, fourteen of which were nine-pounders. A furious battle ensued, with the Pickering emerging victorious. Haraden put first mate Jonathan Carnes on the Golden Eagle , as prize master, along with nine other crewmen from the Pickering . While some of the Golden Eagle s crew were imprisoned on the lower decks of their own ship, the captain, Robert Scott, along with the balance of his men, were brought onto the Pickering .

Two days later, as the Pickering made its final approach to Bilbao, Haraden saw a large lugger of its kind that had ever been fitted out from Great Britain, he assumed the American would try to escape. Instead, Haraden decided to stand and fight.

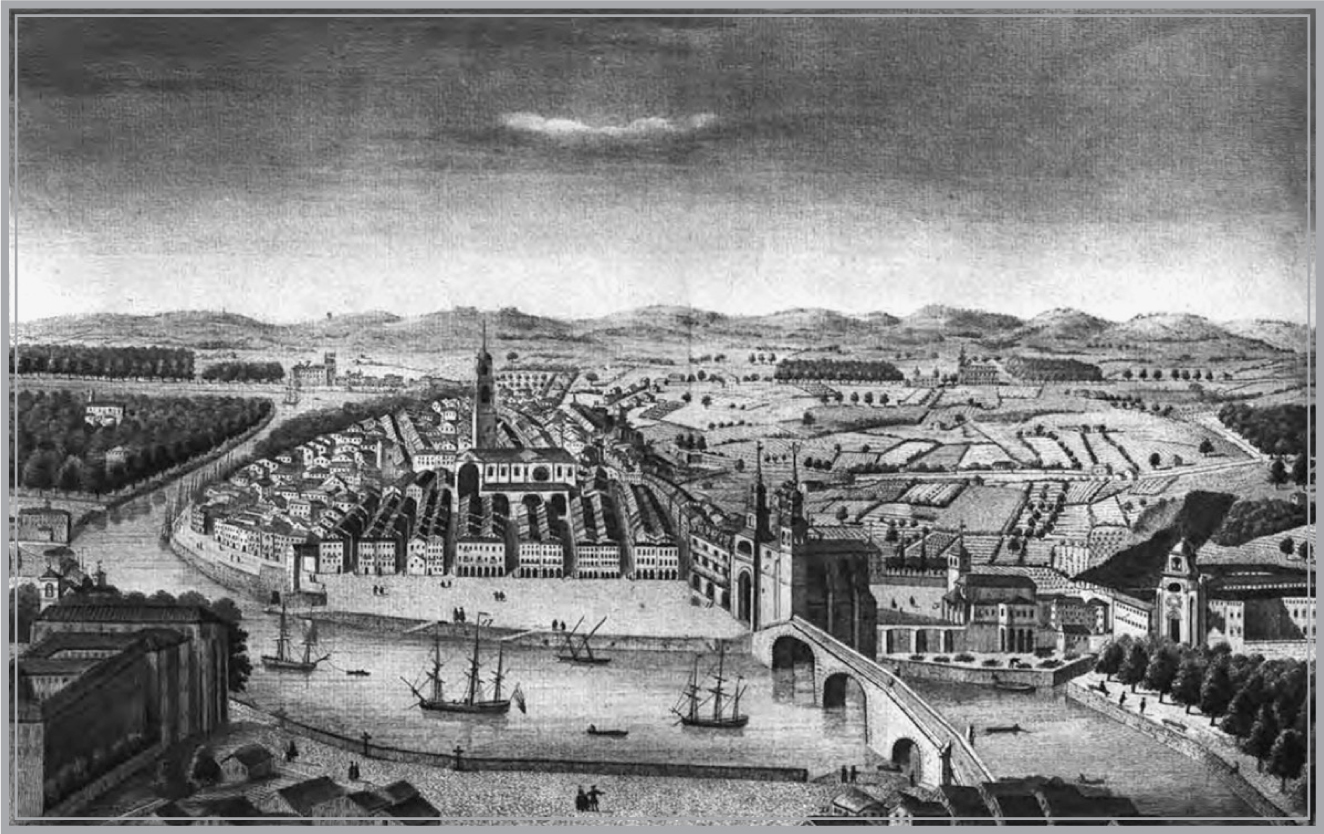

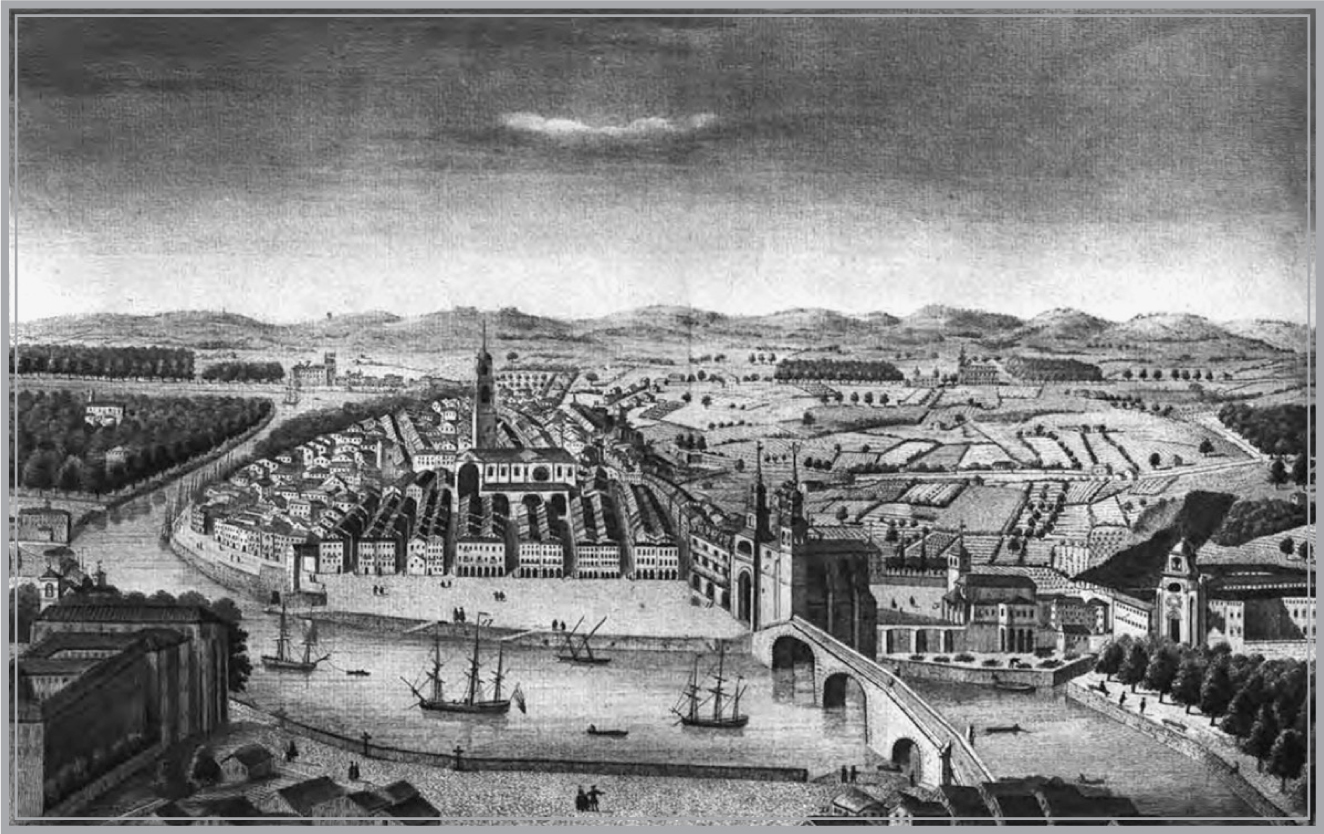

A West View of the Town of Bilbao in Vizcaya , circa 1756.

On its way toward the Pickering , the Achilles easily recaptured the Golden Eagle and placed a prize crew of its own on board. As the sky turned overcast and the night grew darker, Haraden surmised that the Achilles would put off its attack until morning. He retired to his cabin, ordering the watch to keep a sharp eye on the enemy ship and wake him should it approach.

As dawn broke, the Achilles began its advance, and a crewman rushed to alert Haraden. He and went up on deck, as if it had been some ordinary occasion, and surveyed his ship to make sure his men were prepared for the confrontation. Concerned about his diminished ranks, he offered a healthy reward to any of the British prisoners who would fight alongside him. Ten stepped forward.