Acknowledgments

Many people have made this book a pleasure to write. At the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, I thank especially John Hench, Nancy Burkett, and the extraordinary services rendered by Joanne D. Chaison and her staff. In particular I express my gratitude to Laura E. Wasowicz, Curator of Childrens Literature, and to Georgia (Gigi) Brady Barnhill, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts. Gigi went the extra mile, offering me her unparalleled knowledge of the nineteenth-century memorial lithography and sharing with me many slides of the work that she has collected over the years. That the visual arts play such an important role in this project is due in large part to her unfailing helpfulness and energy. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, too, I found ready and enthusiastic assistance. Special plaudits go to Jennifer Ambrose, James Green, Cornelia S. King, Phillip S. Lapsansky, and Erika Piola for enriching my work in numerous ways. Jim Green did a great service in introducing me to Dr. Carol Soltis, whose work on Rembrandt Peale and his painting The Court ofDeath has deeply informed my thinking. Along the way I also received expert help from reference librarians at the New York Public Library, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Historical Society, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Library of Congress, the University of Mississippi, and the Arkansas History Commission. Closer to home, I acknowledge the exceptional reference staff at the Bailey Library of Hendrix College. Peggy Morrison worked wonders with her interlibrary loan skills, collecting pamphlets and photocopies that I would not have dreamed were accessible.

Outside of my research nexus, I received encouragement, support, and wise counsel from numerous quarters. I benefited greatly from attending a 1998 Summer Institute on the history of death in America sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Held at Columbia University under the enthusiastic and able leadership of David and Sheila Rothman, this institute laid the groundwork for many of the ideas and issues explored in this book. I thank all of my fellow participants for stimulating my thought, for suggesting possible source materials, and for being great scholarly pals. Presenting an early formulation of the outline for this book at the Southern Historical Associations annual meeting also galvanized my efforts. Drew Gilpin Faust, Charles Reagan Wilson, and Bertram Wyatt-Brown all offered supportive words as well as cogent critiques. A sabbatical leave and faculty project grant offered to me by Hendrix College allowed me the blessing of time and space in which I could finish my research and complete a draft of my manuscript. I must also point to my students at Hendrix College, who over the past years have taken my courses on the American Civil War and Reconstruction and on the history of death in America. I have learned more than I can say from them. And while I cannot identify each individual student who has contributed an insight that shifted my thinking on a particular topic, I can acknowledge them collectively for their dedication, intelligence, and good cheer. Dear friends and colleagues have also sustained this project by listening to me spin out ideas, by reading snippets of prose, by suggesting sources, and by reminding me that this was a book worthy of writing. Jay Barth, Lloyd Benson, Steve and Martha Goodson, Steven Hornsby, Ian King, Rebecca Resinski, John Rodrigue, Sylvia Frank Rodrigue, Allison Shutt, Martha Sledge, and Mart Stewart have all, in different ways, made this a better book.

I could not have asked for more from my colleagues at Cornell University Press. This book project has lived through three excellent editors, Peter Agree, Sheri Englund, and now Alison A. Kalett. Alison has been a steadfast supporter of this project, offering me thoughtful readings of chapters and helping me to stay focused on its broad interpretive significance. Special credit also goes to those outside readers who read my manuscript for Cornell, Susan Juster and David Waldstreicher. Both of them lavished me with amazingly detailed reports that have made this a much stronger book. I also want to acknowledge Cameron Cooper, Susan Specter, Karen Hwa, my copyeditor, Cathi Reinfelder, and others at the Press for their work on the book.

My wife, Nancy, and my daughter, Mary-Candler, have kept me firmly grounded in the joys of the present even as I have explored the shades of the past. For that great gift, and for more to come, I dedicate this book with love to them.

Introduction

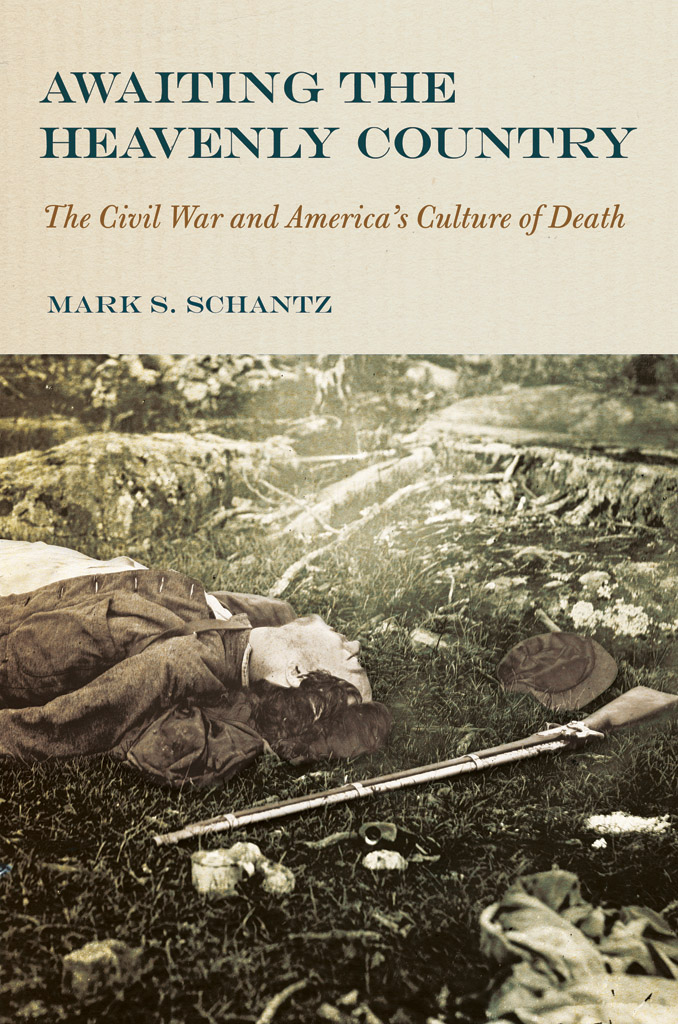

Living under the shadow of postmodernity, where all historical facts are dimly perceived, at least one reality appears horribly luminous: that 620,000 men lost their lives in the American Civil War. Whether we think of the American Civil War as a total war, a destructive war, or simply as a hard war, students of it agree on its singularly bloody impact.

Answers to the question of why so many men perished in the war have typically been mapped on terrain occupied by military and political historians. This is both meet and salutary. Surely developments such as the rifled musket and trench warfare contributed to the stunning level of carnage. Thus, for reasons they only barely understood, such as the sinister effects of microbes, and for reasons they grasped with clarity, such as the causes for which they fought, Americans made a war of catastrophic proportions.

While these military and political explanations of the enormous cost of the Civil War are clearly of great importance, they do not consider the wider cultural matrix in which the war was fought. They ignore what, in my view, must be a paramount consideration in helping us to understand the Civil War: the ideas and attitudes Americans held about death in the middle of the nineteenth century. For if we assume that the ways in which a culture comprehends death shapes the behavior of its members, then we need to understand how antebellum Americans thought of death if we are to gain greater insight into what they did in the Civil War. If soldiers recited the phrase death before dishonor as a common mantra, then we need to know not only what they thought about the ideas of honor and dishonor (subjects about which we know quite a bit) but also what they thought of death itself.

The argument of this book is that Americans came to fight the Civil War in the midst of a wider cultural world that sent them messages about death that made it easier to kill and to be killed. They understood that death awaited all who were born and prized the ability to face death with a spirit of calm resignation. They believed that a heavenly eternity of transcendent beauty awaited them beyond the grave. They knew that their heroic achievements would be cherished forever by posterity. They grasped that death itself might be seen as artistically fascinating and even beautiful. They saw how notions of full citizenship were predicated on the willingness of men to lay down their lives. And they produced works of art that captured the moment of death in highly idealistic ways. Americans thus approached the Civil War carrying a cluster of assumptions about death that, I will suggest, facilitated its unprecedented destructiveness.