Table of Contents

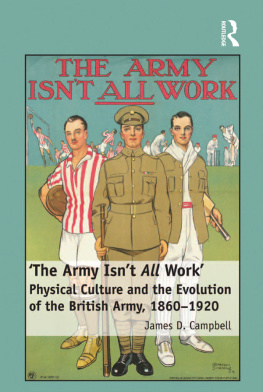

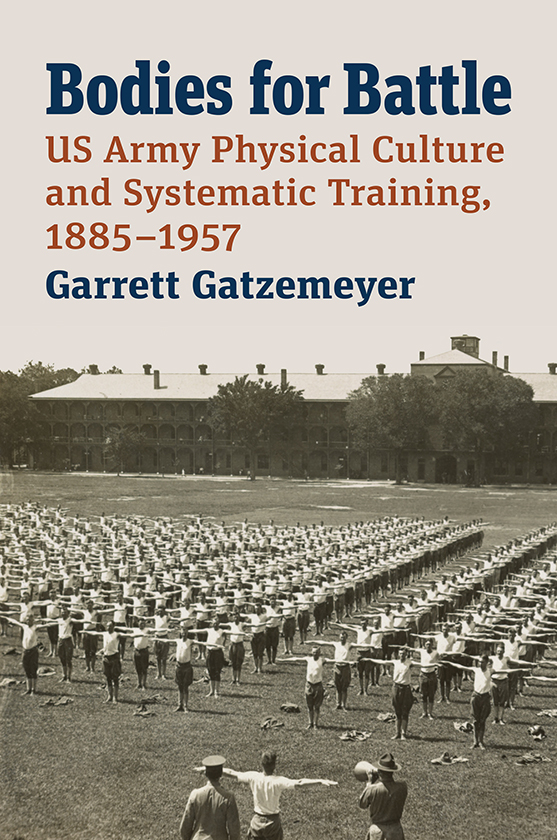

Bodies for Battle

MODERN WAR STUDIES

William Thomas Allison

General Editor

Raymond Callahan

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

David R. Stone

Jacqueline E. Whitt

James H. Willbanks

Series Editors

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor Emeritus

Bodies for Battle

US Army Physical Culture and

Systematic Training, 18851957

GARRETT GATZEMEYER

university press of kansas

university press of kansas

2021 by the University Press of Kansas

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gatzemeyer, Garrett, author.

Title: Bodies for battle : US Army physical culture and systematic training, 18851957 / Garrett Gatzemeyer.

Other titles: US Army physical culture and systematic training, 18851957

Description: Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of

Kansas, 2021. | Series: Modern war studies |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021018726

ISBN 9780700632589 (cloth)

ISBN 9780700632596 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United States. ArmyPhysical trainingHistory19th century. | Physical education and training, MilitaryUnited StatesHistory19th century. | United States. ArmyPhysical trainingHistory20th century. | Physical education and training, MilitaryUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Physical fitnessUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC U323 .G38 2021 | DDC 355.5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021018726.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in the print publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

contents

acknowledgments

This book is the product of time, sweat, and tears, not all of which were mine. Much of the research and writing was shoehorned into late nights, lunch breaks, weekends, and family vacations over the past six years. Many people sacrificed their time, shared their talents, and lent encouragement during these odds hours and over the long haul. Without them I could not have completed this project.

Some of my supporters may not even know that their names are going into print. I am indebted to the librarians and archivists who helped me access obscure documents and offered insights from their own areas of expertise. I think especially of Benjamin Gross from the Linda Hall Library, Mary Brutzloff from the Eisenhower Presidential Library, and Alicia Mauldin and Mark Danley from the United States Military Academys Special Collections and Library. Bethany Davis and David McCartney of the University of Iowa libraries graciously packaged and sent digitized copies of the Charles McCloy papers, saving me thousands of dollars and days of leave. Rebekka Bernotat of the Donovan Research Library found Fort Benning physical training conference reports, the existence of which I only suspected, and then located even more and digitized the whole lot.

A corps of readers and commentators provided a circle of support. Cliff Rogers and Sam Watson, brilliant historians with whom I have had the honor to work, both read and commented on multiple drafts. My manuscript benefited from their insights, and I found their friendship and mentorship to be invaluable. I am also indebted to members of the USMA History Departments informal junior faculty dissertation working group. I thank especially Ben Brands, Jim Villanueva, Mark Askew, John Fahey, and Brendan Griswold for their feedback and for sharing their projects with me. I would be remiss if I did not thank my former division chief, Col. Bryan Gibby, whose encouragement and advice were vital. I doubt that I would have been able to sustain this project had I not belonged to the culture of respect, excellence, and care he cultivated in our division. I am also deeply grateful to readers outside of USMA, especially John Dzwonczyk, Brett Beneke, and Trent Gatzemeyer. Finally, I thank my advisers at the University of Kansas: Adrian Lewis, Jennifer Weber, Sheyda Jahanbani, and Beth Bailey. Professor Lewis asked hard questions and kept me on track. Professor Weber challenged me to be a better writer and more critical thinker. Professor Jahanbani offered her wisdom in this projects earliest stages, probably without even realizing it. Professor Baileys insightful feedback, curiosity, and expertise helped me take this project to a new level.

I am most obliged to my immediate family. My father, Steve Gatzemeyer, listened to me when I was at a low point and encouraged me to drive on. He is a model of dependability and solid character. Amy, my incredible wife, deserves an entire book to detail her contributions. Amy believed in my work from the beginning, sacrificed our time together, accepted periods in which I was mentally or physically distant during the writing process, and actively labored to keep me energized and balanced. She also read every draft, which is a remarkable accomplishment. Finally, I thank my children: Quenby Anne and Theodore Rex. They did not always understand why I had to hide somewhere to write, or why we went on family vacations to archives, but they were always ready with a hug or word of encouragement. Like Amy, they sacrificed our time together to bring this project to completion. It is to them that I dedicate this manuscript and a lesson I learned while writingnearly anything is possible given planning, determination, dedication, and the support of those whom you love.

introduction

modern war, modern fitness

The US government selected Ely J. Kahn for service in the US Army in 1941, relabeled him Private Kahn, and dispatched him to training. Before long, Kahn found himself sweating in a field in South Carolina, sharing in an early morning combat-preparation ritual common to the experiences of millions of American soldiers that began with a brisk dose of calisthenics. During those physical drill sessions, Kahn remembered his officers exclaiming that every exercise would develop some especially useful muscle, warning their charges not to bend those knees as we strove earnestly to touch our toes, and urging the troops on by announcing that every uncomfortable position we got ourselves into was for our own good. That was one of Kahns great lessons: You dont have to be in the Army long to learn, from some superior or other, that everything you do, or that is done to you, is for your own good. What Kahn and his peers may not have realized is that their officers had more in mind than muscular strength and cardiovascular endurance when they spoke of exercises doing soldiers good. In truth, the workouts were part of an uplift project intended to produce better men in a holistic sense: more disciplined, more resilient in the face of adversity, and more morally upstanding. While some elements of that uplift project could claim a general heritage from warrior cultures stretching back through millennia, the particulars of Kahns exercise ritual were less than a century old.

Kahns enforced early morning routines were grounded in an eternal fact: war is physical. In combat, fortune favors the soldier in better condition. Superior conditioning enables troops to fight longer and harder, to move farther and faster, to carry heavier loads and endure greater hardship. These relative advantages can be the difference between life and death, victory and defeat. The Prussian philosopher of war Carl von Clausewitz once observed that War is the realm of physical exertion and suffering. These will destroy us unless we can make ourselves indifferent to them, and for this birth or training must provide us with a certain strength of body and soul.

university press of kansas

university press of kansas