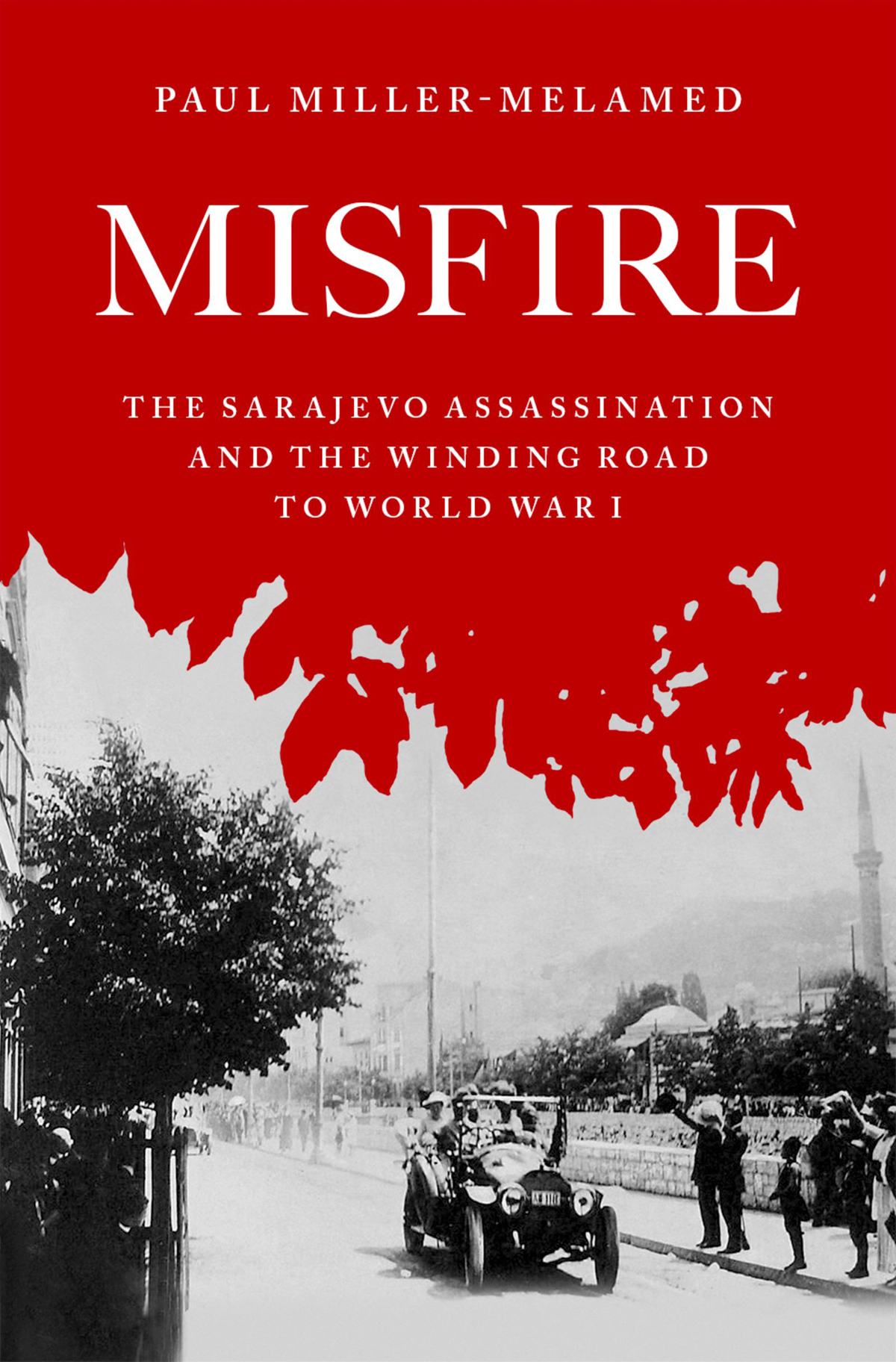

Misfire

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780195331042

eISBN 9780197620014

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780195331042.001.0001

For my parents

again, and always

But is not the pastness of the past that much more profound, complete, and fabulous the closer it is to the present? And it may well be that our history, by its very nature, shares some other things with fables as well.

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain (1924)

Contents

when i signed a contract to do a book on the Sarajevo assassination for its 100th anniversary in 2014, I expected it to be a fairly straightforward project. After all, I was already writing about remembrance and representations of Archduke Franz Ferdinands political murder. A short narrative history of this well-known event seemed like a welcome break from the theoretical torments of memory studies, not to mention the tangible sensitivities of Serbs and Austrians to what I was saying about how they constructed their pasts. Moreover, there were already so many books on the Sarajevo assassination that I hardly expected any hard archival work would be necessary. I thus held off writing until a year before the manuscript due date. That was my first mistake.

The second was in assuming that this singular deed was well understood. The deeper I dug into the past of the political murder as opposed to its ever-changing present, the more I became aware that there was no consensus whatsoever about the origins and motives of the plot to kill the Habsburg successor. Indeed, about the only thing authors generally agreed on was that it was a great, earthshaking event organized by fanatic Serb nationalists in an ultra-secret conspiratorial society ominously named Unification or Death (and colloquially, though no less menacingly, called the Black Hand). The intrigue, in short, was necessarily intriguingafter all, as everyone knows, it sparked the First World War. Thus came my third mistake, the one I no longer regret despite its steep toll in lost sleep: I started by drafting an Introductiona professional transgression, since historians are typically taught to save the Intro for lastthat drew attention to how the assassination is commonly depicted even as it assured readers that what followed was merely a concise history of the political murder embedded into a broader account of the origins of World War I. In other words, my scholarly work was infiltrating my straightforward assignment.

Thankfully, Oxford University Press, and in particular my acquisitions editor, Susan Ferber, did not drop me in favor of a more conventional, if timely, version of the archdukes political murder. I very much hope that this book will live up to their expectations, even if does not align with their original intentions for the recent centennial.

Likewise, I am appreciative of those scholars who, in and around 2014, have done pathbreaking work on both the Sarajevo assassination specifically and the origins of World War I writ large. No less than three excellent collections on the political murder have appeared since the centenary, and I have found something useful in almost every chapter. The same goes for the new volumes on the Balkan Wars, the fresh biographies of Franz Ferdinand, and the wave of works on the July Crisis, not to mention Christopher Clark and Margaret MacMillans erudite overviews of the Great Wars origins. Most important, my book has benefited immensely from John Zameticas research and insights in , the first study to surpass Vladimir Dedijers classic account of the road to Sarajevo in over half a century.

Because this book project merged with my ongoing work on how we process the political murder, it gives me great pleasure to finally (and formally) thank the granting agencies to whom I am, quite literally, indebted. In no particular order, these are the Fulbright Program, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Wilson Center, the American Philosophical Society, and the European Unions Marie Skodowska-Curie Actions. Of course, I could not have taken advantage of these generous fellowships if not for the unstinting support of administrators and colleagues at McDaniel College, who let me loose from my teaching duties in order to ramble about Europe or sit tight to write. These fine faculty and devoted educators include Donna Evergates, Bryn Upton, Ted Evergates, Stephen Feeley, Joan Develin Coley, Tom Falkner, Julia Jasken, and the late great Samuel Case.

Of course too, if not for the academic input and unconditional support of colleagues and friends, I could hardly have maintained the momentum to see this book to completion. Foremost, my grad school buddy Talbot Imlay patiently read (and reread) the evolving Introduction, gingerly commenting on its inconsistencies and incoherencies, among other issues. Bosnia expert Robert Donia and my comradely co-editor (for a different book) Claire Morelon gave the entire manuscript a thorough reading and its author an equally comprehensive lesson in scholarly professionalism. All of them set aside their own projects in order to improve mine, as did Oxfords three anonymous peer reviewers. Thanks are not only in order, but also in earnest.

Other academics (and students!) who generously gave of their time and knowledge to my Sarajevo obsession, whether it was writing a reference letter, reading a chapter, translating a document, editing a draft, or simply pointing out a new source, are almost too numerous to list. But heres a go, starting with my talented research assistant and treasured friend Saa Gai: James Abdu, Wladimir Aichelburg, Christopher Brennan, Mark Cornwall, Andreas Danielsen, Duan Gliovi, Emily Greble, Tracee Haupt, Guido van Hengel, Catherine Horel, Enes Kari, Dieter Mahncke, Annika Mombauer, Andy Murphy, Grayson Myers, Pierre Purseigle, Oliver Rathkolb, Erwin Schmidl, Rebecca Sharp, Paula Sutter Fichtner, Danilo arenac, Milo Vojinovi, Andrew Wachtel, Samuel Williamson, and numerous archivists and librarians scattered about the Balkans, sequestered in small offices in Central Europe, and practically living at the Library of Congress. As for the latter, I should like to single out Grant Harris and his staff in the European Reading Room, where much of the writing took place and all the works I ever needed were readily made available.

And now to the longest list of allfriends who never let me forget that I was doing meaningful work, and how much I meant to them. Heartfelt thanks to Stephen Batalden, Michle Bonnet, Anouar Boukhars, Karen Cantor, Tomek and Magda Chudak, Charles Dellheim, Nicole Dombrowski-Risser, John Eglin, Laura Gross, David Herrmann, Paul Kennedy, Stphanie Laithier, Christianna Leahy, Vered Lev Kenaan, Tracey Adelstein and Rick Levine, Jacob Melish, John Merriman, James Najarian, Herlinde Pauer-Studer, Michaela Raggam-Blesch, Heinz Rene Pecina, Dan O. Ripp, Jeff Rosenberg, Joanne Rudof, Herb Smith, Susan Smith, Sue Somers, Vincent and Sigrid Viaene, and my Viennese buddy who died way too early, Tom Mueck.