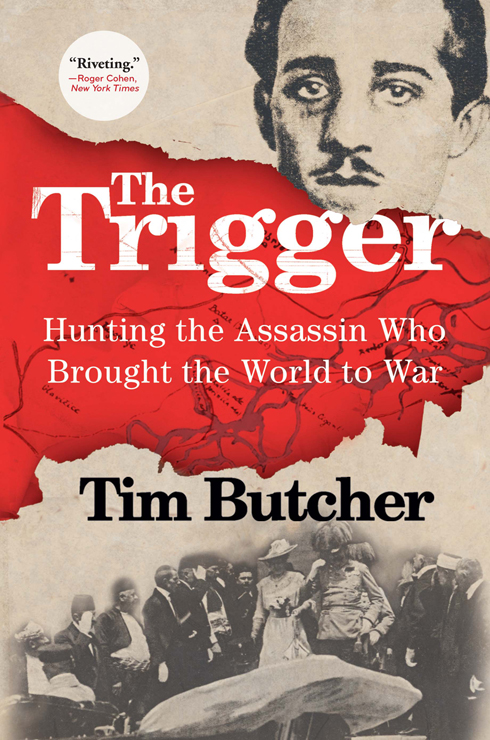

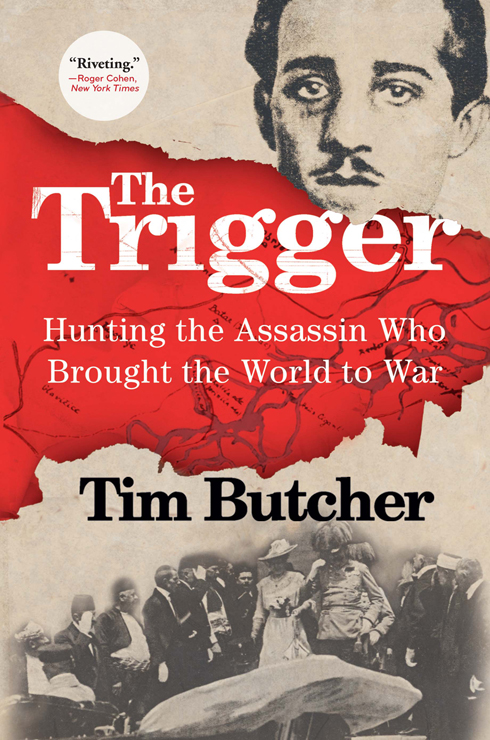

The Trigger

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Blood River: A Journey to Africas Broken Heart

Chasing the Devil: The Search for Africas Fighting Spirit

The Trigger

Hunting the Assassin Who Brought the World to War

Tim Butcher

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2014 by Tim Butcher

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Chatto & Windus an imprint of Random House

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2325-1

eISBN 978-0-8021-9188-5

Jacket front photography: Gavrilo Princip Topfoto;

Background map: the National Archive of Bosnia and Hercegovina;

Bottom photograph: The Illustrated London News Picture Library, London,

UK /The Bridgeman Art Library

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/ Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

14 15 16 17 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my greatest shapers

Stanley and Lisette

CONTENTS

NOTE ON PRONUNCIATION

The anglicised version of Bosnian, Serbian and Croatian spelling has been used in The Trigger . Pronunciation largely follows that of English letters although with the following exceptions:

c is ts as in tsar. Hence the name Princip is pronounced Printsip

j is y as in yam. Hence the town Jajce is pronounced Yaitsay

is ch as in scratch. Hence the town Glamo is pronounced Glamotch

is a softer ch. Hence the name Filipovi is pronounced Filipovich

r can be used as a rolled r vowel sound as in purr. Hence the Vrbas River is pronounced Vurrbas

is sh as in shin. Hence the word for tent, ator, is pronounced shator

d is a hard j as in gin. Hence the name Dile is pronounced Jillay

dj is a soft j as in jack. Hence the name Hadji is pronounced Hajee

is a yet softer j as in pleasure. Hence the name Draa is pronounced Drarjer

The Trigger

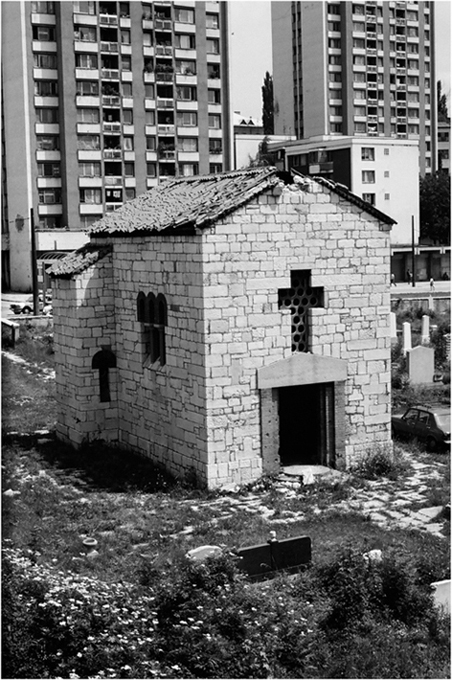

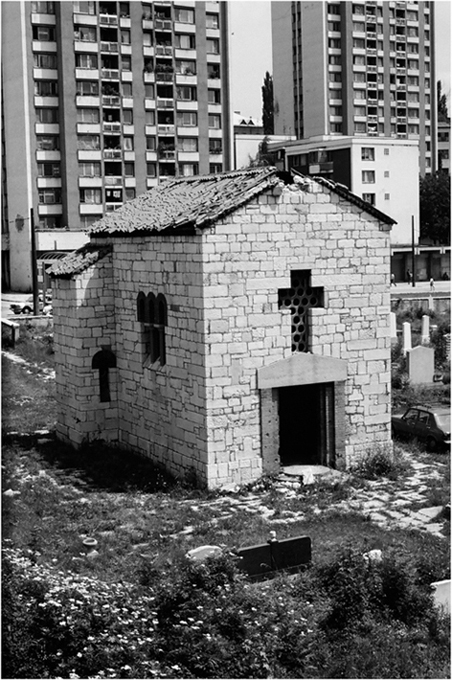

Gavrilo Princips war-damaged tomb

PROLOGUE

T his story springs from many sources, but the most powerful one for me was a discovery I made at a street market in Sarajevo, back when the city was under siege in 1994. I was a young reporter sent by the Daily Telegraph to cover the Bosnian War, which had begun two years earlier in this land of mountain and myth. Shelling had often made it too dangerous for civilians to venture outside in their capital city, but during a lull in the firing I joined locals as they reclaimed the streets. One afternoon I walked into an open area busy with people reduced by the war to selling possessions laid out in piles across unswept pavements. Pickings were meagre: half-worn brake pads from cars that had not run in years, a set of taps unused because of no mains water. I took a photograph of an elderly man sitting under an umbrella, shaded from the July sun, as he sold cigarettes one by one.

And then I noticed people occasionally slipping away from the market to visit a stone building on the edge of a nearby cemetery. I went to explore.

It was about the size of an electricity substation, a modest structure with a box design, easy to overlook. It wore the livery of so many wartime buildings in Sarajevo: a cavity from what appeared to be an artillery strike, terracotta roof tiles rucked out of alignment, the door ripped from its hinges, its frame pockmarked by shrapnel. I followed the market-goers and, in the summer heat, my sense of smell told me from some distance what was going on. They were using it as a makeshift lavatory. My diary recorded it in malodorous detail:

The graveyard was unkempt but I was not prepared for what I found... The floor was just a sea of turds. Amongst the mess were dozens of used sanitary towels, a bra and lots of rubbish. A tombstone lay smashed in two on the floor and the light hung wrecked from the ceiling which had a gaping hole in it.

But what made me curious was that the building was clearly some sort of chapel. A cross was visible above the doorway. Why be so disrespectful of a religious site?

I found the answer on a piece of black marble set into an external wall. It was a commemoration stone bearing the date 1914 and some Cyrillic text, including a list of names. At the top of the list, in the most prominent position, was one that jumped out at me:  , Gavrilo Princip.

, Gavrilo Princip.

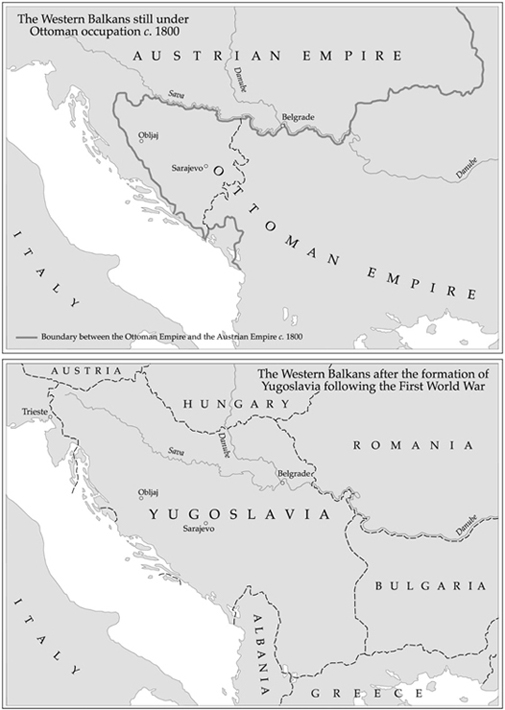

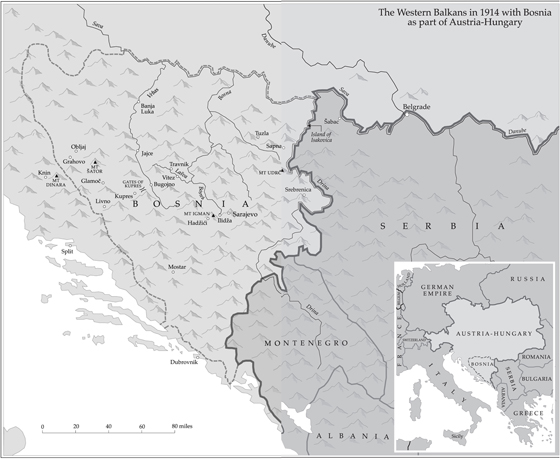

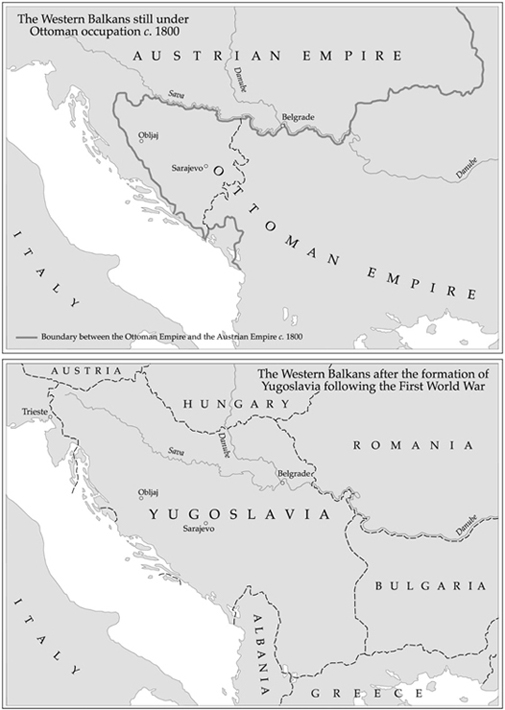

When I went to Sarajevo for the first time as a reporter, a single thought kept coming to me: this was where the event took place that triggered the First World War, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip. As a schoolboy I remember struggling to pronounce the killers name, but as I grew older my understanding of the crisis he precipitated became clearer millions of lives lost in a clash so colossal it reshaped the world. Yet the Bosnian War of the 1990s seemed far removed from the fighting of the Great War, a localised, ethnic conflict in the Balkans, a region synonymous in Western eyes with impenetrability, backwardness and violence. For much of the twentieth century Bosnia had been one of the component parts of Yugoslavia, but when its leaders in Sarajevo sought to create their own separate country they clashed with the Serbian authorities who dominated the Yugoslav nation and who opposed the break-up. Tens of thousands were to die in fighting that, if you took away the helicopters, wire-guided missiles and satellite navigation systems, seemed to belong to an earlier, more brutal age: deliberate attacks on civilians, torching of homes, systematic rape, genocide.

Sarajevo was where many of the Bosnian Wars defining horrors took place. In early exchanges, forces commanded by Bosnian Serb hardliners had been able to secure only a few of Sarajevos peripheral suburbs, so they withdrew to the high ground that presses in on this cupped hand of a city and set about imposing one of the cruellest sieges in modern warfare. The lights went out, taps ran dry and supplies dwindled to a trickle, condemning 400,000 Sarajevans to survive on the collapsing skeleton of their home town. Their tormentors suffered no such supply problems and were able to dictate the nature and pace of their assault.

Next page

, Gavrilo Princip.

, Gavrilo Princip.