Published by

Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

Oxbow Books and the individual authors, 2011

ISBN 978-1-84217-989-5

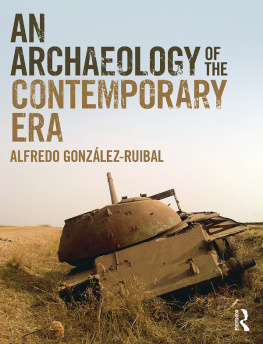

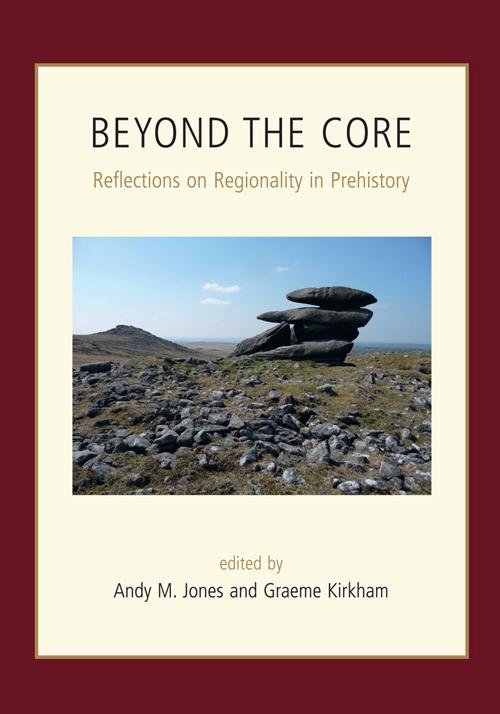

Front cover image. A Bronze Age tor cairn at Showery Tor, Bodmin Moor. (Photograph: Graeme Kirkham.)Back cover image: The Neolithic chambered tomb of Coetan Arthur at St David S Head, Pembrokeshire.

(Photograph: Graeme Kirkham.)

This book is available direct from:

Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

(Phone: 01865-241249; Fax: 01865-794449)

and

The David Brown Book Company

PO Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA

(Phone: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468)

or from our website

www.oxbowbooks.com

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beyond the core : reflections on regionality in prehistory / edited by Andy M. Jones and Graeme Kirkham.

p. cm.

This book arose from a session at the Theoretical Archaeological Group conference, which was held in December 2006 at the University of Exeter.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-84217-989-5

Digital Edition ISBN: 978-1-842-17588-0

1. Archaeology--Great Britain--Congresses. 2. Great Britain--Antiquities--Congresses. I. Jones, Andy M. II. Kirkham, Graeme. III. Theoretical Archaeology Group (England)

DA90.B49 2011

930.14--dc22

2010054179

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Hobbs the Printers Ltd, Totton, Hampshire

Contents

1. Regionality in prehistory: some thoughts from the periphery

Andy M Jones

2. Borders and belonging: exploring the Neolithic of the Anglo-Welsh borderland

David Mullin

3. Moving on in landscape studies: goodbye Wessex; hello German Bight?

David Field

4. Pattern, perception and preconception: recognising regionality in Scottish prehistory

Stratford Halliday

5. Scale and senses of belonging: thinking about regionality in the Neolithic of the Irish sea zone

Vicki Cummings

6. Social and geographical scale: regionality and the Cumbrian stone circles

Helen Evans

7. Islandscapes and standing stones: homogeneity and difference

Joanna Wright

8. The Alien Within: the forgotten sub-cultures of Early Bronze Age Wessex

Andrew Martin

9. The Botrea barrow group: regional identity in Early Bronze Age Cornwall

Andy M Jones

10. Into the west: placing Beakers within their Irish contexts

Neil Carlin

11. Something different at the Lands End

Graeme Kirkham

12. Any questions?

Richard Bradley

List of contributors

R ICHARD B RADLEY

University of Reading

N EIL C ARLIN

University College, Dublin

V ICKI C UMMINGS

University of Central Lancashire

H ELEN E VANS

University of Sheffield

D AVID F IELD

English Heritage

S TRAT H ALIDAY

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland

A NDY M J ONES

Historic Environment, Cornwall Council

G RAEME K IRKHAM

Historic Environment, Cornwall Council

A NDREW M ARTIN

University of Bournemouth

D AVID M ULLIN

University of Reading

J OANNA W RIGHT

University of Manchester

Regionality in prehistory: some thoughts from the periphery

Andy M Jones

Introduction

This book arose from a session at the Theoretical Archaeological Group conference, which was held in December 2006 at the University of Exeter. The idea had developed as a result of discussions with colleagues from both the academic and contractual sphere, who have been undertaking archaeological work in various parts of Britain, and especially those in the south-west peninsula, who felt that the archaeological narratives of their regions were being subsumed by the evidence from a relatively small geographical area, which has dominated the study of prehistory since the latter part of the eighteenth century, namely the chalkland uplands of Wessex.

This situation undoubtedly occurred because Wessex contains a range of iconic monuments such as Stonehenge and Avebury, and its soils permit levels of preservation, which many other areas do not. Furthermore, geography has played its part, as the regions easily accessible location within central southern England, in easy reach of several museum and university departments, has meant that it was much better studied through the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries than any other region in Britain at the time when the idea of prehistory was being formulated. Antiquarians such as Colt Hoare (1821), and Thurnam (1869; 1891) set about excavating and, most importantly, widely publishing the results of their labours to wider audiences; these readers were more easily able to view the Wessex sites, than those on the Yorkshire Wolds, the Highlands of Scotland or the moors of the south-west peninsula.

Subsequently, throughout the twentieth century archaeologists have spent much of their time finding links between identifiable strands of evidence, such as commonly found ceramic forms or widely occurring monument types to create larger synthetic narratives. Again there has been an understandable tendency to work from the familiar, so it is little surprise that the most influential synthetic model in the first half of the twentieth century was Stuart Piggotts 1938 paper on the Wessex Bronze Age, which firmly established the idea of a Wessex culture. Although few people today would follow this model in its entirety, the fact remains that it is the only region in England which has been the focus for frequent updated syntheses (for example, Stone 1963; Grinsell 1957; 1958; Piggott 1971; McOmish et al 2002; Lawson 2007). Similarly, despite the more recent move towards the identification and interpretation of the particular practices of prehistoric communities, all too many studies are still devoted to what are perceived to be the well understood core areas. In fact, even many of the regionally based studies which have appeared in recent years are actually devoted to areas within Wessex (for example, Brck 1999; Peters 2000 and Watson 2001). This imbalance is even greater when one considers the ever increasing collection of books and papers on Wessex sites such as Stonehenge and Avebury (for example, Pollard and Reynolds 2002; Cleal et al 1994; Darvill 2006) far outweighs that of any other area of Britain. This is despite the fact that most recent archaeological fieldwork has occurred away from the iconic chalkland monuments. Indeed, even books which are not wholly focused on prehistoric Wessex often use Stonehenge in the title (Burgess 1980 Gibson 1998; Gibson and Sheridan 2004; Larsson and Parker Pearson 2007).

However, it would be entirely unfair to lay the blame for any disparities in the study of British prehistory solely at the door of archaeologists who work in southern England, as it could also be argued that until comparatively recently, relatively few archaeologists across the British regions have taken very much interest in constructing their own distinctive local narratives or with challenging the dominance of the established Wessex sequence. Indeed, regardless of local differences in the archaeological record, much effort has in the past been given by archaeologists working in the regions into fitting their findings into the bigger picture. Burials and monuments and material culture recovered from archaeological sites around the country were frequently described in terms of Wessex artefact typologies, monument forms and burial rites. In fact, given the dependency on relative dating, and the small-scale nature of most pre-war excavations, this was probably the only way for the discipline to develop the models needed to explain British prehistory to a wider audience in a comprehensible way.