Inside the dimly lit shipwreck galleries of Fremantles Maritime Museum lies the skeleton of one of Australias first European settlers. It cramps in a shallow stone casket hewn from the rock shelf where the young man was hastily buried. His bones are bleached but also damaged, hacked with savage blows from the weapons of the castaways who killed him.

Looming over the remains is another set of bones. These are the splintered timbers of the ship that carried the young man and his murderers across the globe, casting them onto the jagged reefs of the great Southland. These skeletons of bone and woodthe hulking ship and her small sailorare times survivors. Dredged from the sea and its stone islands, these remains of incomprehensible violence are now officially artefacts. They rest within a public museum and are legally protected by lawful acts of government. This gives them historical value that they did not have in the obscure past they inhabited. It was not until they were excavated from their next-to-last resting places by the finders and keepers of archaeological records and registers that they attained their value as memento mori. Now their remains can be preserved, interpreted and displayed for those who enter the purpose-built sepulchre that signifies the worth we accord them in the present. They are officially as well as technologically protected from further harm.

They need to be. The forces and interests that have turned a lost boys bones and the Batavias once mighty timbers into artefacts have also imparted great monetary value. Their mortal remains, what they wore or carried, the spikes and pegs that held their floating world together and, of course, the treasure she carried, are prized by the unofficial plunderers of the past, the looters of lost lives and shattered ships. The demand for sunken relics from the history zoos and galleries of the world is insatiable, fuelling a fierce and almost invulnerable economy of illegal booty hunting and murky global transactions. The irony is that the thousands who sailed here in hundreds of vessels were also raiders as well as traders in skin and bone. Now we revere and commemorate them while we revile those who steal their remains.

Those who came to the unknown shores of the Southland, along with the great sailing craft that bore them, are now here forever. Australia is their home as well as their grave. Their remains and residues will continue to be sought by looters as well as by archaeologists, historians and other researchers. Our need to know about these ghosts and their stories is powerful and deep. Whether we call this heritage, history or tradition, it is a compact we desire with those who have lived and died before us. The eighteenth-century French philosopher, Voltaire, famously said that history is only a pack of tricks we play upon the dead. Less frequently quoted is the rest of his observationif some useful end is served, it does the dead no harm as, in any case, they have tricks of their own.

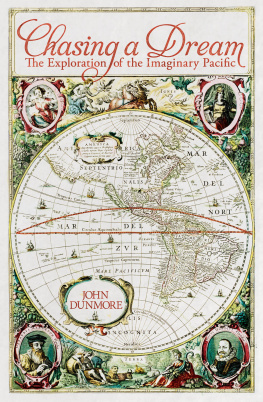

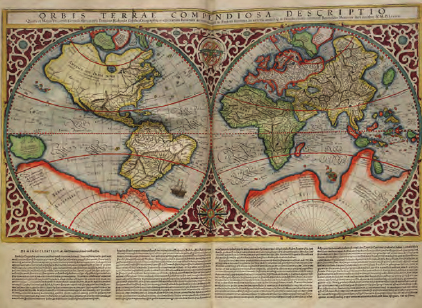

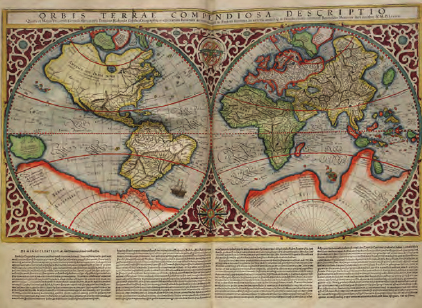

Planisphere made by Rumold Mercator, 1587 from the Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (published 1595). From at least the fifth century BC, the Greeks were aware that the world was a globe and speculated about a large landmass in the extreme south to balance the lands they knew in the northern hemisphere.

The dock of the Dutch East India Company at Amsterdam, 1696, by Ludolf Bakhuizen. Keen to discover a new source of gold, spices and other valuable goods, the Dutch East India Company sent many ships to explore the Southland, and mapped much of the coast between 1606 and 1756.

Source: Amsterdam Museum

Uniform for soldiers of the Dutch East India Company by H. Rolland, 1783.

Source: Nationaal Archief, The Hague

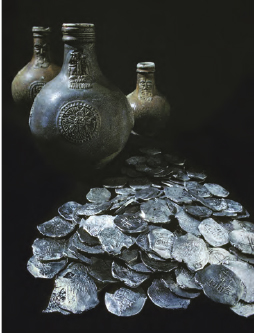

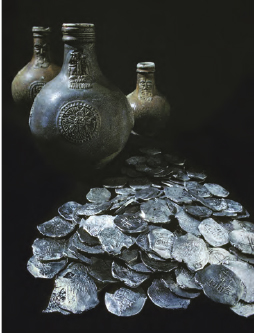

Beardman jugs and pieces of eight from the wreck of the Vergulde Draeck following conservation treatment. On 4 October 1655, the Dutch United East India Company ship set sail from Texel, carrying a cargo of trade goods worth 106,400 florins, together with eight chests of silver coin worth 78,600 florins, and the crew consisted of 193 men. The vessel was lost on 28 April 1656 on a reef off the coast off Western Australia, north of Yanchep near Ledge Point.

Photo: Patrick Baker, courtesy Western Australian Museum

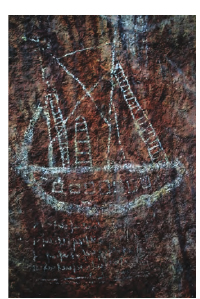

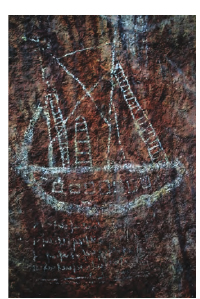

Rock paintings of ships such as this one at Walga Rock, inland Western Australia, clearly indicate both coastal and inland Aboriginal people were well aware of passing European ships.

Courtesy of Tim Bowden

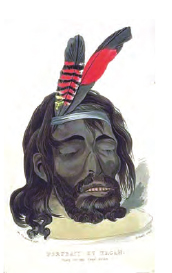

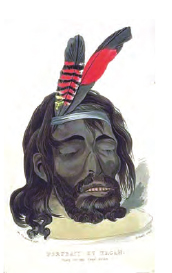

Yagan (b. circa 1795 and d. 1833) was an Aboriginal warrior of the Noongar people, who played a key part in early resistance to British settlement in the area surrounding what is now Perth in Western Australia. This is an illustration of Yagans severed head by George Cruikshank and appeared as the frontispiece of Robert Daless 1834 booklet A descriptive account of the panoramic view &c. of King Georges Sound and the adjacent country.

Camp on the Peron Peninsula, Shark Bay, Western Australia, 1818, by Alphonse Pellion.

Source: National Library of Australia

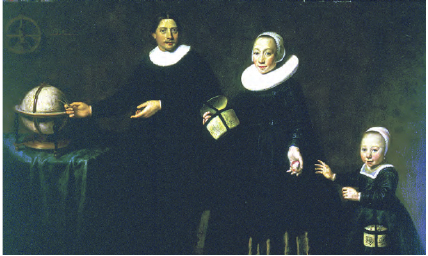

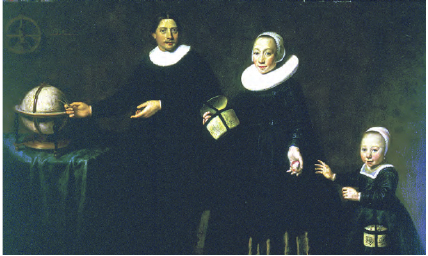

Portrait of the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman with his wife and daughter by Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp. In 164243 Tasman, commanding two ships, reached Tasmania and the east coast of New Zealand.

Source: Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra

Captain James Cooks landing at Botany Bay, 29 April 1770, home of the Gweagal people, where he claimed the east coast of Australia on behalf of the British Crown. Illustration from Town & Country, 1872.

Source: Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra

The secret map Nova Tabula, Insularum Iavae, Sumatrae, by Willem Lodewijcksz, 1598, created to illustrate the achievements of the voyage of the Dutch fleet to the East Indies under Cornelius de Houtman from 1595 to 1597. It covers southern Malaya, Sumatra, Java, southern Borneo and the islands east of Java. It was withdrawn from the book in which it was to be published, as the Dutch authorities wanted to restrict access to information which could be used by rival trading companies.

Next page