Copyright 2013 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used

for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hashim, Ahmed.

When counterinsurgency wins : Sri Lankas defeat of the Tamil Tigers / Ahmed S. Hashim. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4452-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Tamilila Viutalaippulikl (Association)History.

2. CounterinsurgencySri Lanka. 3. InsurgencySri Lanka.

4. Tamil (Indic people)Sri LankaPolitics and government.

5. Sri LankaHistoryCivil War, 19832009. I. Title

DS489.84 .H375 2013

954.93032 2012045106

For SharaIntroduction

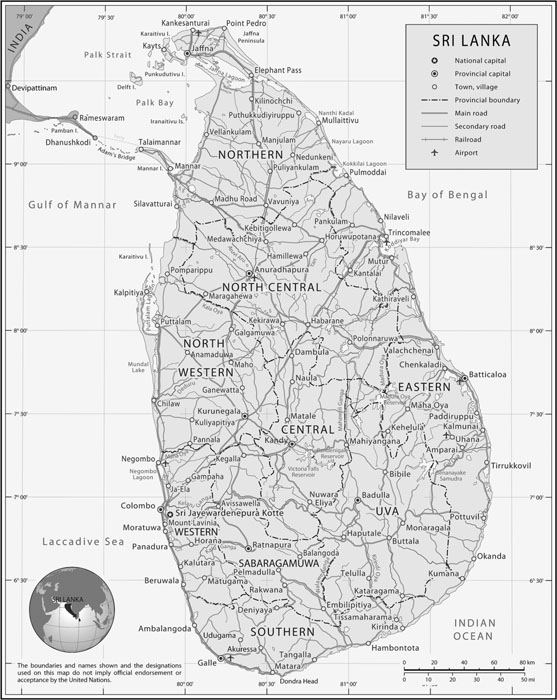

A few hours ago our troops recovered the body of the worlds most ruthless terrorist. Thus came the announcement by General Sarath Fonseka, commander of the Sri Lankan army (SLA), on May 19, 2009, heralding the death of Vellupillai Prabhakaran, founder and leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. VP, as Prabhakaran was known, along with his family and much of the senior leadership of the movement, had been killed at or near Karayanmullivaikal, a village on a thin strip of coastal land sandwiched between the Nandi Kadal lagoon to the east and the Indian Ocean to the west. This was not far from Puthukkudiyiruppu village, VPs traditional headquarters and an area that had witnessed intense and bloody fighting between the SLA and the once formidable Liberation Tigers during the final phases of the war in April and May 2009.

The circumstances of VPs death and those of his family and the top leadership of the movement in the space of twenty-four hours remain unclear. Were they shot in the heat of battle? Were they killed as they tried to surrender? Were they executed after they surrendered as a result of orders from above? The facts remain classified by the government, but numerous speculative theories have made the rounds. Nonetheless, the decapitation of almost the entire leadership of a movement remains without precedent in the struggle between a government and an irregular entity. It is quite possible that the top government political and military leadership decided to prevent the escape of the Liberation Tigers (LTTE) leadership. If VP and his closest subordinates had escaped, they might have rallied the struggle from overseas. Capturing them alive would have presented Sri Lankan authorities with considerable headaches and calls for release to move overseas or for a free and fair trial that might have gained the movement more traction.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, or LTTE, were crushed and annihilated, marking a signal and unprecedented victory for the governments counterinsurgency (COIN) campaign. This was reflected in the speech Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa gave on May 19, 2009, in which he

It has been rare in contemporary war for one side to declare victory unequivocally and the other to concede defeat so readily. The magnitude and decisiveness of the victory is compelling reason enough to study this case of insurgency and counterinsurgency. It is, without a doubt, the first counterinsurgency victory of the twenty-first century. But it is not without controversy, as the accusation of human rights abuses by the government that began in the closing weeks of the war have continued to be heard, and magnified.

The Roots of Conflict

When Ceylonas Sri Lanka was then knownbecame independent in 1948, it was a fortunate country (to paraphrase a term often applied to Australia, the lucky country). Ceylon had one of the highest human development indices of any Asian country at the time. It had a vibrant economy and a seemingly stable parliamentary system bequeathed by the founders of parliamentary rule, the British. Everyone thought it was a country set up for success. Yet this early assessment turned out to be hopelessly optimistic. There were simmering tensions below the surface between the two major ethnic groups in the country, the Sinhalese and the Tamils, over distribution of resources and goods, and the ideological direction of the country. As tensions deepened, each side became wedded to an exclusivist communitarian nationalism; moreover, each felt itself to be the genuinely aggrieved party. The delicate political system proved incapable of reconciling the irreconcilable. The inevitable result was violence, and the eruption of political conflict and then war has proved enormously costly. Violence has hindered sustained economic development, prevented the country from devoting resources to modern infrastructure, promoted mass emigration, and lost the beautiful island nation lucrative revenue from tourism.

The active military phase of war in Sri Lanka began on July 23, 1983, when a group of militants from the newly formed LTTE ambushed and killed thirteen Sri Lankan soldiers on patrol in the area of Thirunelveli, near the city of Jaffna. The soldiers were from the majority Sinhalese community; the insurgents were Tamil. The soldiers funerals became emotionally charged, setting off the worst intercommunal violence the country had experienced. Groups of Sinhalese civilians went on a rampage in the south; Tamil businesses and houses were torched, and hundreds of Tamil civilians, including women and children, were killed. Although the exact number of dead is disputed, estimates range from 400 to 3,000.

The authorities turned a blind eye toward and at times even actively encouraged the violence. Security forces often stood by as Tamils were slaughtered. Tamil youths, already weary of their elders failure to achieve redress of grievances by peaceful means, were traumatized by harrowing stories brought back to the north by survivors. Violence and vengeance were on their minds, and they responded accordingly. Naturally, the Sinhalese retaliated, and because they had the material resources of and paramilitary groups associated with the state, their response in the early days was more extensive, and more brutal.

A yawning chasm opened between the two communities, which was exploited by the LTTE and right-wing anti-Tamil Sinhalese politicians. The civil war was on. It lasted twenty-seven costly years. Not surprisingly, most observers, both inside and outside Sri Lanka, came to view the conflict as an intractable and protracted war that appeared to defeat all efforts at either military resolution or peaceful settlement. When the war erupted again in spring 2006 after a four-year lull, the consensus was that the hapless country was in for yet another episode of bloodletting that would settle nothing. The international community would have to step in yet again and try to mediate between the warring parties. Imagine the collective global surprise when the Sri Lankan armed forces wiped out the LTTE in May 2009: it was as sudden as it was unexpected. Sri Lanka remains at peace, much to the relief of the population. Although terrorist cells have been uncovered and arms caches secured, not one successful terrorist incident has taken place since the wars end.