Editors

Niro Kandasamy

School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Nirukshi Perera

Prehospital, Resuscitation and Emergency Care Research Unit, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

Charishma Ratnam

Monash Migration and Inclusion Centre, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

ISBN 978-981-15-1368-8 e-ISBN 978-981-15-1369-5

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1369-5

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This Palgrave Pivot imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

The registered company address is: 152 Beach Road, #21-01/04 Gateway East, Singapore 189721, Singapore

Foreword

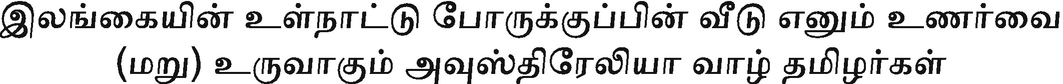

In the everyday Jaffna Tamil idiom with which I grew up, the wordviidu(more phonetically,vuudu), was often paired with another term,vaasal. Usually translated as house and home or house and property, the alliterative phraseviidu-vaasalperhaps more closely evokes household: the tangible and intangible attributes, belongings and relations that make up a home. On its own, however,vaasaldenotes a spatial feature such as a door-step, entry-way or threshold, an intermediate space between the world outside a house and its interior.Vaasalis that which distinguishes outer from inner, demarcates the familiar and domestic and orders the space between home and not-home. To lackviidu-vaasalis not only to lack a roof over ones head, but to be more deeply disoriented, to have ones boundaries displaced; it is to be profoundly unhomed in the world.

In the context of Sri Lankan Tamil diasporic communities and individuals in Australia, the editors of this collection pose the question:

What are the different ways in which dislocation has shaped expressions of home?As they discuss, experiences of dislocation and expressions of home are intimately bound up, the dimensions of the one defining the shapes and meanings of the other.

The Incomplete Thombuby the artist T. Shanaathanan is an unbearably poignant, uncategorisable work that seeks to explore precisely these relational contours of loss and home. Remembered ground plans of their homes drawn by people displaced from the Jaffna region during the war are superimposed on to architectural plans of those same sites and are further layered with the respondents brief recollections of home and the artists own drawings in response to their stories. In this interplay of words and imagesthe embodied forms of the respondents own words and hand-drawings, the spare precision of the architectural ground plans and Shanaathanans own visual commentarieslost homes (including temples, orphanages, bunkers and farms) unfold in both their complex spatiality and their immateriality. They emerge as spaces that are at once deeply embodied and constitutively intersubjective. Trees, plants, household deities, animals and everyday objects , as much as family and neighbours, give shape and meaning to that which is lost and orient the speaker in space and time:

My grandfathers house is the house I always long for There was a medicine room in his house filled with all kinds of bottles and jars in unusual shapes with images of gods. In one of the rooms my grandpa used to keep popular magazines and books. I used to spend most of my time in that room. The room was also occupied by a hatching hen. People stayed at the house till late. At the time of their departure, looking over the palmyrah grove, I could see numerous stars dotted around the sky. (Shannathanan 2011, p. 62)

Bringing together multiple subject positions and approaches, this volume seeks to explore the ways in which diasporic Tamils who are refugees and migrants from the war shape their homes in Australia. As Ratnamohan, Krishna, Mares and Silove point out in their chapter, home encompasses both inner psychic space and anthropological place. The contributions explore both senses of home through lenses ranging from memoir and fiction to ethnography, cultural analysis and trauma studies, exploring specific diasporic formations (the Tamil weekend) and groupings (Tamil-Australian activists, women displaced by the war). As the editors recognise, diasporic Tamils are not a unified or singular category. Dislocations over three decades of the war compounded and ramified to produce their own exclusions as well as new political and affective communities. Tamil-speaking Muslims expelled from the Jaffna peninsula in the early years of the war by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam constitute a distinct category of those displaced by the war. In Australia, Tamil asylum seekers and refugees caught in indefinite offshore detention test the limits of diaspora as an analytic term. New configurations like the latter in turn produce their own forms of cultural expression. Shaminda Kanapathi, effectively imprisoned by the Australian state on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, for more than six years, is a frequent voice for

Manus Alert, an irregular form of digital telegram by which the men held on Manus reach out to the wider world. Marking the sixth anniversary of offshore detention in July 2019, Kanapathi, who was in his early twenties when he sought refuge in Australia, made an impassioned plea in the national press calling for his long deferred future to be finally allowed to begin:

We are hoping against hope that this new government can finally recognise and admit this appalling waste of human life and offer us hope with positive action towards providing us with a future, a safe home to build our dreams. (Kanapathi 2019)