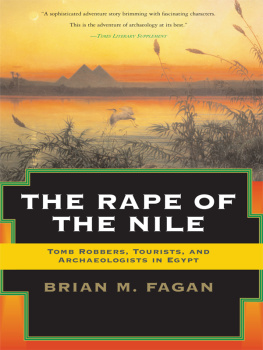

Archaeologists, Tourists, Interpreters

Bloomsbury Egyptology

Series Editor

Nicholas Reeves

Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation , Ian Shaw

Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt , Wolfram Grajetzki

Court Officials of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom , Wolfram Grajetzki

The Egyptian Oracle Project , Robyn Gillam and Jeffrey Jacobson

Hidden Hands , Stephen Quirke

The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt , Wolfram Grajetzki

Performance and Drama in Ancient Egypt , Robyn Gillam

To invisible interpreters.

In Memoriam, Steven Seymour, an interpreter.

Archaeologists, Tourists, Interpreters

Exploring Egypt and the Near East

in the Late 19thEarly 20th Centuries

Rachel Mairs and Maya Muratov

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

This book is an offshoot of a project-in-progress on multilingualism and the complex roles of interpreters in antiquity, based on epigraphic and literary sources of the Hellenistic and Roman periods from the Northern Black Sea, Rome, Western Roman Provinces and Egypt. It began in the spring of 2008 with a series of conversations about interpreters ancient and modern that took place on the third floor of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), New York University, where we both were Visiting Research Scholars. We are grateful to the director of ISAW, Roger Bagnall, for the opportunities provided and for creating a stimulating environment where the seeds of this venture were first sown.

This book has been a collaborative venture throughout, but each author has taken special responsibility for particular sections. Rachel Mairs prepared the introductory chapters, material on Petrie and Lawrence and the section on Solomon Negima. Maya Muratov prepared the conclusion, material on Finati and DAthanasi, Woolley, Mallowan and Christie, American expeditions and the section on Daniel Z. Noorian. Any first person references within the text should be understood in this light, but the books broader arguments are the product of joint research and discussion.

Among many people who have contributed to the making of this book, we would like to thank the following: Nicholas Reeves, for his encouragement of this project; Charlotte Loveridge, formerly of Bloomsbury, and Alice Reid and Anna MacDiarmid, of Bloomsbury, for their constant help with the manuscript; the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments; James Moske and Barbara File, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, for allowing access to the Noorian files and for permission to use them in our book; Dan and Patty Baumgartner, of Rogue River Books, for information on the testimonial book of Solomon N. Negima; and the many book and antique dealers who have helped us gather dragoman ephemera, such as the postcards illustrated in this book. More such pieces are discussed on the Hermeneis blog (http://hermeneis.wordpress.com/).

Our colleagues, friends and family members provided moral, intellectual or other kinds of support along the way: Arietta Papaconstantinou, our parents, Raymond and Carol Mairs and Boris and Adelaida Potapov; Cyrill Muratov; Roberta Casagrande-Kim; Tiziana dAngelo.

This book is dedicated to the many invisible interpreters whose stories are buried in the accounts of others.

Rachel Mairs and Maya Muratov

Oxford and New York, October 2014

A brief aside in the Palestinian-American literary critic Edward W. Saids memoir Out of Place offers an insight into what it has meant to interpret the Middle East to Western consumrs, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Saids paternal grandfather, he tells us, at some point in his life was a dragoman who because he knew German had, it was said, shown Palestine to Kaiser Wilhelm (Said 1999: 6). for travellers whose lack of Arabic or Turkish would otherwise have made it impossible for them to interact with and understand their surroundings. On the other, his role was to protect his clients from the more inconvenient or uncomfortable aspects of travel. The employment of a dragoman enabled a foreign visitor to insulate him- or her-self from the Orient in a way which offered an illusion of engaging with it. What they came to know about the Orient was mediated through the filters of their own observations and preconceptions, and their dragomans explanations and interpretations.

European and American travellers in Egypt and the Middle East in the second part of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, the period covered by this book, were consumers in several senses. The act of travelling was in itself an act of conspicuous consumption, a new luxury for well-off members of the upper and middle classes. With the advent of the first Thomas Cooks package tours to the Orient in the 1860s70s, travel in the region was, to an extent, rendered a commodity, which one might show off to ones friends and contemporaries. So many tourists of the period wrote and published accounts of their travels some of them without either literary merit or intrinsic interest that the genre became worthy of satire. Travellers were consumers of culture, ancient and modern, and they were a market for everything from genuine antiquities to tourist tat. But they were also representatives of colonial powers, of foreign mechanisms of control which consumed the resources of the Middle East.

We have used the term Orient because this is the way in which contemporary European and American travellers conceived of the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, as a region whose history and culture stood as an antithesis to their own. By the 1970s, the historical project of interpreting the Orient to the Occident had been recognized as inseparable from the history of Western colonial domination. Edward Saids Orientalism showed how Western cultural representations of the East including the accounts of travellers without expressly political motives for their presence in the region reproduced romanticized, exoticized images which served to justify Western colonial dominance. An example to which we shall return is that of the French novelist Gustave Flauberts notes on his stay in Egypt (184950), and more specifically his account of a night spent in the company of the dancer and courtesan Kuchuk Hanem. As Said notes, Kuchuk Hanem:

never spoke of herself, she never represented her emotions, presence, or history. He spoke for and represented her. He was foreign, comparatively wealthy, male, and these were historical facts of domination that allowed him not only to possess Kuchuk Hanem physically but to speak for her and tell his readers in what way she was typically Oriental. (Said 1978: 6)

We are not in a position to give Kuchuk Hanem back her voice, but there are ways in which Western historical accounts of the Orient and Orientals can be made to yield information on the lives of their subjects from different perspectives. Recent projects such as Stephen Quirkes study of the archaeologist Sir W. M. Flinders Petries Egyptian workforce show how archival materials, in particular, provide wonderful opportunities to explore the lives, professional expertise and even personalities of the apparently faceless and voiceless Oriental masses (Quirke 2010). In this book, we endeavour to do the same for the dragomans who worked for Western travellers and sojourners in Egypt and the Near East, including archaeologists. Dragomans are doubly handicapped in terms of their historical visibility: as Orientals, and as interpreters, whose role in a transaction is usually regarded by the client as solely one of transparent mediation, without regard for the myriad social and cultural cues which the interpreter must also translate, or choose not to (Venuti 2008). The stories which we tell in the following chapters come from different sides of the linguistic and cultural transaction between East and West. The published accounts of Western travellers and archaeologists offer a client-driven perspective on dragomans the writers own, and other peoples. In these, for the most part, the Oriental man, in the form of the dragoman, no more speaks for himself than does the Oriental woman Kuchuk Hanem. Archival documents and photographs allow us a slightly different perspective. Sometimes, we are fortunate enough to have a dragomans own words, or a more impartial account of his activities than that of a (sometimes disgruntled) client.