The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

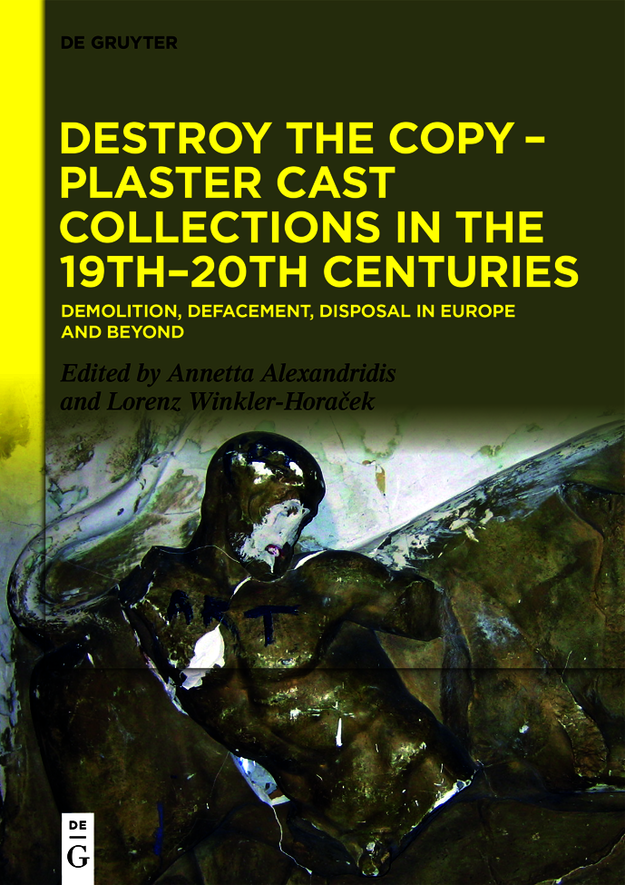

Casts and Their Discontents

Cornell universitys plaster cast of the Olympia metope depicting Heracles and the Cretan bull this books cover image is beyond repair (). Numerous cracks run through the heros neck and the area where the bodies of man and animal overlap. Smaller pieces have broken off, leaving a deep scar in Heracles chest and a hole in the bulls flank. The fresh white breaks stick out from the rest of the surface, which is covered with a brown-greenish varnish to evoke the color of patinated, ancient stone. The coating has been abraded in the upper part of the relief, exposing the white plaster. Very fine scratches attest to the attempt to rid the cast of its varnish with wire brushes. The relief has suffered heavily from this vigorous intervention, which ultimately did not yield the desired result. At some point, white paint was brushed over the bulls back and splashed into Heracles face. Earlier, the hero had been given blue eyes and bright red lips. Im Art was written in dynamic dark blue brush strokes on the heros head and chest. All in all, the cast presents physical traces of various layers of destructive gestures, some of them curatorial in intent such as the removing of the varnish, others more explicitly iconoclastic such as the added lipstick or graffito.

Fig. 1: Heracles and the Cretan Bull, cast of metope from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia with various traces of manipulation, Cornell University.

If it was non-canonical in aesthetic terms, it soon became part of the canon for historic reasons, as material testament to the famous site of the Olympic games and the comprehensive German excavations which, instead of removing the original sculptures, were only allowed to take molds of them and distribute the casts. Read against this background, the Im art could emphasize or ironize the status of the relief as a work of art as opposed to a teaching tool or archaeological document. One could spin this further and further, as the interplay between various interpretations of prototype and replica allows for numerous twists.

The call, however, is for historically situating such moments if we want to understand destruction as a form of reception. This does not always prove to be easy. Instances of damage done to objects in custody of an institution are often clouded in uncertainty or rumor. Events during which casts were thrown from windows or into elevator shafts in the 1960s are attributed to various art academies. As spectacular as they are, these reports do not always turn out to be true. restored, or completely discarded.

Fig. 2: Casts of the statues from the west pediment of the Temple of Athena Aphaia at Aegina; Black Athena-Display at the exhibition Firing the Canon: The Cornell Cast and Their Discontents; Weinhold Chilled Water Plant, Cornell University, 2014.

Original, Copy, Multiple Casts in Time and Space

Why should we care? This volume hopes to provide some answers. It is the first collection of articles explicitly devoted to the theme of the destruction of plaster casts. Plaster cast collections of European, especially Renaissance, but most of all Greco-Roman sculpture have had and in part still have a major impact on art/artistic production, the development of taste, aesthetic norms, and specific ideas about the human body. While this is primarily true for Europe, colonialism and imperialist power constellations facilitated the spread and influence of such collections all over the globe. As plaster cast collections played a fundamental role, not only in fine arts training, but in establishing art history and especially classical archaeology as academic disciplines and their methods, their fate is intimately linked to the position Western art and its related institutions held and hold within higher education, scholarship, and the broader public. Plaster casts were also instrumental in globalizing knowledge of Western art, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Their destruction or discarding therefore poses several questions. What triggered it? Was it a reaction against aesthetic hegemony of the Western canon and/or the institutions that embodied and promoted it? A more symbolic act of resistance against authoritarianism in politics and society? A coup against capitalism and consumerism? A big clean-up to rid oneself of petrified traditions or simply of dusty trash cluttering museum spaces? New aesthetic and artistic agendas? Who orchestrated it, how, and when? And first and foremost: What, actually, was the target? The individual cast, its prototype, the multitude of replicas, plaster as material that can be smashed so spectacularly, or all of the above?

Such questions have so far not been addressed in depth,

All that does not exclude a general timeline. On a global level, for example, the history of cast collections can be seen as marked by a spectacular boom in the late 19th century, deliberate and violent destruction in the 1950s and 1960s and their aftermath, followed by eventual resurrection in the later 20th century. Both the enormous success and the equally dramatic demise of casts is generally attributed to their status as copies, as mechanically produced replicas. Yet, while this apparently neat timeline suggests a narrative entirely driven by politico-economic and/or aesthetic agendas, things are unsurprisingly much more complicated and unclear. Casts, again, are multiples and thus connect multiple nodes in time and space.

Each of the contributions in this volume investigates such nodes in the form of a case study. The papers present various strands of scholarship, most importantly a traditional art-or socio-historical and archival one, namely the reception of classical antiquity with cast collections as one of its special fields, and the material side of postcolonial theory as exemplified in studies on the museum and the object. Whereas the former usually leave out the hegemonic mission of cast collections,

Targets of Destruction Iconoclasm, Iconoclash?

The individual papers in this volume discuss different historical scenarios of destruction, defacement, or discarding of casts. Besides war bombings, the majority exemplifies indirect, hidden, casual, mundane (unprofessional handling or storage, recycling), subversive, While this might partly be due to the lack of explicit documentation much of what we know of such events is based on anecdotal evidence or rumor it also seems a function of the historical and conceptual complexity of plaster casts (as in part outlined above).

Even though the papers assembled here do not share a particular theoretical approach, Igor Kopytoffs concept of object biography offers a helpful framework to group them together, for it captures the changing status and trajectories of casts depending on their (cultural) value. It is especially apt for understanding why plaster casts were seldom completely taken out of circulation. Constantly moving between the ideal polar types of singularization and commoditization, their life never ended with destruction, disfigurement, or other forms of manipulation, such as paint, scratches, restorations, breaks etc. or changing contexts of display. Casts always had or regained value and meaning for somebody.