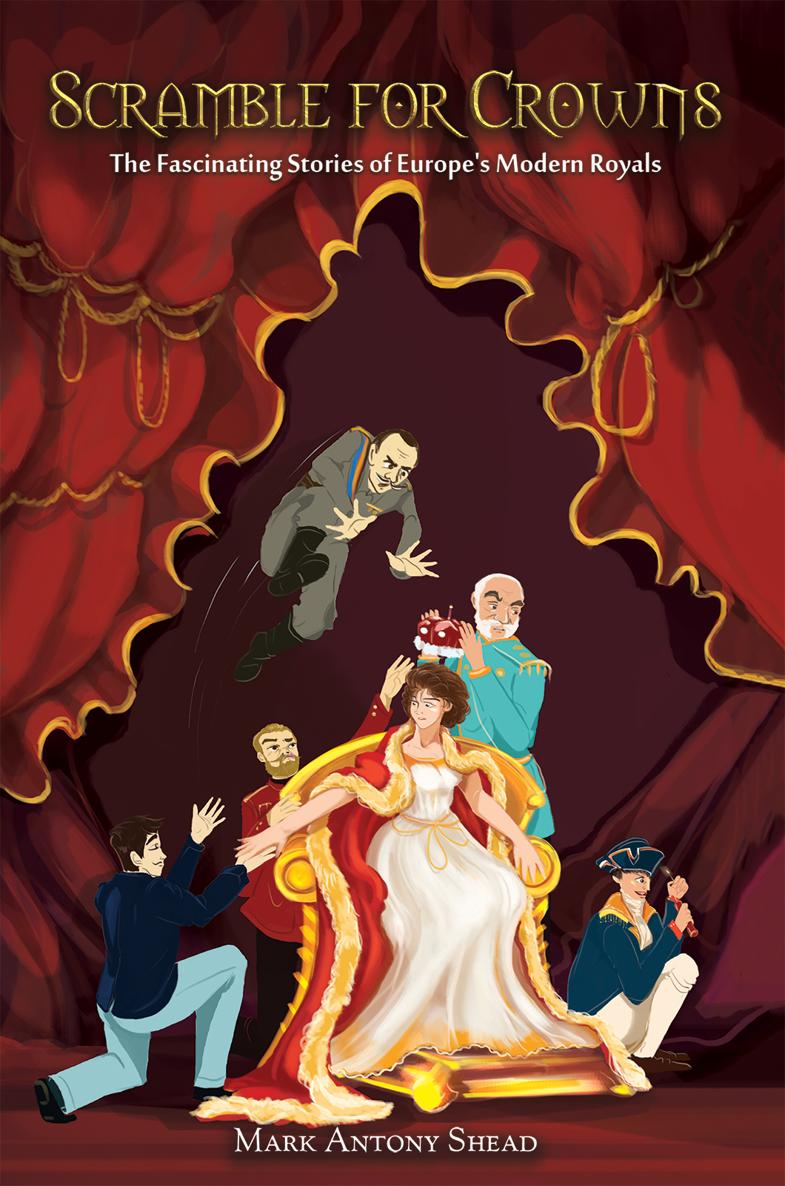

S cramble for C rowns

The Fascinating Stories of Europes

Modern Royals

Mark Antony Shead

Austin Macauley Publishers

2021-09-30

Scramble for Crowns

About the Author

Mark Antony Shead was born in 1990 in the London Borough of Bexley, where he has lived much of his life to date. He graduated from the University of East Anglia in 2012 in modern history, before starting his career as an account manager in Japanese reinsurance business at Aon.

Dedication

With thanks for the support of my Aon colleagues, friends and family, and special thanks to Jerad for the chat over a few beers in Canada that made this book happen.

Copyright Information

Mark Antony Shead (2021)

The right of Mark Antony Shead to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with section 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781528990905 (Paperback)

ISBN 9781528990912 (ePub e-book)

www.austinmacauley.com

First Published (2021)

Austin Macauley Publishers Ltd

25 Canada Square

Canary Wharf

London

E14 5LQ

Preface

One of the much-cited assets of the institution of monarchy is that it is associated with continuity, which in turn is associated with stability. And on the face of it, you can see why. With a republic, it is difficult to predict who the head of state will be in five to ten years, let alone twenty to fifty years. But with a monarchy, it should be a very different story. After all, when a Briton looks at a photograph of their royal family today, one that includes Queen Elizabeth II and princes Charles, William and George, it would not be unreasonable for that Briton to expect to be looking upon their present and future national leaders for the rest of their lives. But, if modern history is anything to go by, no European can take the institution of monarchy for granted. Just over one hundred years ago (increasingly the length of an average human lifespan), an overwhelming majority of Europeans had a royal as their head of state. And yet, today, Europes reigning kings and queens, princes and grand dukes are now clearly in a minority, as their numbers have been whittled down for a variety of reasons, whether brought down by the barricades of revolution, the bayonets of war or the ballot boxes of modern democracy. Thus, if we look at the experiences of Europes modern royals as a whole, whilst we can sometimes see an orderly succession, in recent times there has also clearly been a scramble for crowns, a scramble to take or to keep the thrones of Europe, with mixed results.

This book recounts the fascinating stories of twenty-six royals from across Europe who have shaped, and been shaped, by the modern era. Although each chapter focuses on an individual, all of their stories are in some way interwoven and overlap and, collectively, they outline the experiences of royal houses, of countries, and of Europe generally. Moreover, the extensive intermarriages between European royals and dynasties over the generations expand the relationships we are about to see from normal international relations to family ties as well. Monarchys reliance on the accident of birth rather than elections also ironically means that, despite the narrow gene pool, in some ways we get the opportunity to see a greater range of people than is generally the case with politicians: more of a balance between leaders who are male and female, old and young, good and bad, wise and foolish.

Monarchys heyday appears to have passed, but royals still reign in 10 European countries (12 if you include non-hereditary monarchies as well) and, as you will see, just because a monarchy comes to an end does not mean that the corresponding royal families suddenly disappear without a trace. Of course, to cover every monarch (or head of a royal family) in every European country would be an epic task, and an epic read. That is why, to ease you in, what follows is a selection of stories that combine the drama and variety that modern European monarchy has to offer. The chapters are in a chronological order, based on when the individual concerned either inherited their respective crown or claim to a crown, occurring at any time from the French Revolution of 1789 until the present day. To anticipate potential confusion, when referring to claims to a throne or crown, this means someone who is regarded by their supporters as the monarch of a country that has been reformed into a republic. At the end of this book are the Gallery, which puts faces to the names of those covered by a chapter, and the Appendices: the first providing an overview of the reigning royal houses featured in this book, and the second an illustration of the closest descendants of Queen Victoria of Great Britain, to demonstrate how tightly linked many of Europes leaders really were.

Napoleon

Coat of Arms of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French

Only 10 years earlier it would have been impossible to predict not only that, after centuries as a kingdom, France would be reformed as an empire, but that the well-established monarchical principle of hereditary succession would be disregarded to allow a commoner (i.e., someone of non-royal blood), Napoleon Bonaparte, to become its first emperor in 1804. Napoleon proved to be not just any commoner though.

By the end of the early modern era, the Kingdom of France ranked amongst Europes Great Powers (and was arguably its foremost) which also included the Kingdom of Great Britain (soon to become the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland), the Holy Roman Empire (shortly to be reformed as the Austrian Empire), the Russian Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia, the latter covering the north of present day Germany and beyond into the east. However, exasperation with Frances ruling elite amongst certain elements of French society culminated in the French Revolution of 1789, which brought the early modern age to an end, and marked the beginning of the period often characterised as modernity. Though the Revolution was not initially directed at the monarchy, the attempt by King Louis XVI to flee the country in disguise, out of fear of the Revolutions continued escalation, made the French royal family enemies of the state. Thus, France was declared a republic, while the guillotine, the efficient alternative means of execution whereby a blade was dropped onto the victims neck within a wooden frame (as opposed to the more haphazard technique of an axe-wielding executioner), was used to end the lives of the King and Queen of France. The number of targets for further executions spread like wildfire, and the guillotines victims would soon include the revolutionary leaders themselves that had advocated using it in the first place.

The repercussions of the Revolution would soon be felt elsewhere, as European leaders rushed to condemn the execution of King Louis and his wife, Queen Marie Antoinette. This was in solidarity not only with the French monarchs as fellow royals but also as family members; this deeper relationship resulting from the historic interbreeding of European royalty that had been encouraged as a means to securing alliances. Queen Marie Antoinette herself was a classic case of this, as she was born an Austrian Archduchess and therefore a member of the House of Habsburg. Tensions between revolutionary France and royal Europe soon culminated in war. However, war abroad with the combined forces of Europes other Great Powers, and escalating unrest at home, soon exhausted France and she burnt herself out. Out of Frances ultimate defeat in the Revolutionary Wars however emerged a figure who had been repeatedly associated with French victories overseas: Napoleon Bonaparte. The man who had risen through Frances military ranks would now do the same in politics until, in 1804, Napoleon had himself duly crowned Emperor of the French.