The Capture of the USS Pueblo

The Incident, the Aftermath and the Motives of North Korea

James Duermeyer

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3555-2

2019 James Duermeyer. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

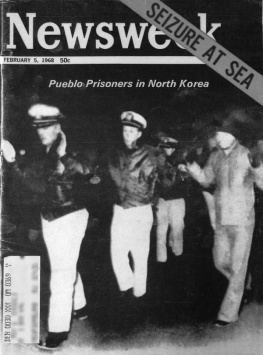

Front cover images from top: Crewmen of USS Pueblo (AGER-2) leave a U.S. Army bus at the United Nations Advance Camp, following their release by the North Korean government at the Korean Demilitarized Zone on 23 December 1968 Representatives of the United States and North Korean governments meet at Panmunjom, Korea, to sign the agreement for the release of the Pueblo crew, 22 December 1968. Major General Gilbert H. Woodward, U.S. Army, Senior Member, United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission, is in the left foreground, with his back to the camera USS Pueblo (AGER-2), off San Diego, California, 19 October 1967 (official U.S. Navy photographs)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the brave officers and enlisted men of the USS Pueblo who suffered months of cruel torture and mistreatment at the hands of their North Korean captors. In spite of the physical and psychological damage inflicted on the crew, their faith and hope sustained them in their darkest hours. I salute them all.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to my wife, Janet, who encouraged me in my goal to take a different and fresh look at the fate of the USS Pueblo and its crew.

I also wish to thank Dr. Joyce Goldberg, professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington, who kindly encouraged me, and offered sage advice while I wrote the book.

Abbreviations

AGTRAuxiliary General Technical Research

AKLAuxiliary Cargo, Light

CandCCommand and Control

CIACentral Intelligence Agency

CINCPACCommander in Chief Pacific

CINCPACFLTCommander in Chief Pacific Fleet

AGERAuxiliary General Environmental Research

CDRCommander

COMINTCommunications Intelligence

CNOChief of Naval Operations

CNFJCommander Naval Forces Japan

COCommanding Officer

COMSEVENTHFLTCommander Seventh Fleet

CTCommunications Technician

DIADefense Intelligence Agency

DMZDemilitarized Zone

DPRKDemocratic Peoples Republic of Korea (North Korea)

DTGDate Time Group

ELINTElectronic Intelligence

HUMINTHuman Intelligence

IFFIdentification Friend or Foe

JCSJoint Chiefs of Staff

JRCJoint Reconnaissance Center

KORCOMKorean Communist

KPAKorean Peoples Army (North Korea)

KWPKorean Workers Party (North Korea)

KGBCommittee for State Security in the Soviet Union

LBJLLyndon Baines Johnson Library

LCDRLieutenant Commander

LTLieutenant

LTJGLieutenant Junior Grade

MACMilitary Armistice Commission

MIGMikoyan-Gurevich (Former Russian Aircraft Builder)

MNDMinistry of National Defense (North Korea)

NAVSECGRUNaval Security Group

NKNNorth Korean Navy

NMCCNational Military Command Center

NSANational Security Agency

NSCNational Security Council

ROKRepublic of Korea (South Korea)

ROKJCSRepublic of Korea Joint Chiefs of Staff

ONIOffice of Naval Intelligence

ONIPOffice of Naval Intelligence Publications

PFIABPresidents Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board

SDSStudents for a Democratic Society

SECDEFSecretary of Defense

SIGINTSignal Intelligence

SITREPSituation Report

U.N.United Nations

UNCUnited Nations Command

USSUnited States Ship

USSRUnion of Soviet Socialist Republics

Preface

The attack and seizure of the USS Pueblo by the North Korean Navy on a frigid day in January 1968 captured world attention and angered the American public during one of the most tumultuous decades in U.S. history. Further fanning national furor was the death of one crew member and the imprisonment of the Pueblos crew of eighty-three American sailors. The Pueblo incident was another of many distracting issues that sidetracked the presidency of Lyndon Johnson. Historians Warren Cohen and Nancy Bernkopf Tucker opined that, In many ways the Pueblo affair proved a fitting capstone for a troubled presidency. Of course, the Pueblo incident assumed a low priority in comparison to the Vietnam War, the overarching geopolitical obsession of the Johnson presidency.

Within the command structure of the U.S. Navy, which I was part of for twenty years, never-ending debates swirled about where to place the blame for the loss of the ship and crew. Historical, hide-bound Navy tradition dictates that the commanding officer of a U.S. Navy ship is ultimately responsible for whatever happens to a ship under his/her command. This tenet serves well, unless the Navy has overloaded the command with numerous restrictive directives. Questionable leadership within the National Security Agency (NSA) and the Navy placed the Pueblo in an indefensible situation. Using the ultimate responsibility axiom, myopic Navy leadership took steps to punish Commander Lloyd Bucher and other crew members for what the Navy perceived as their lack of action against the North Korean attackers. In its narrow focus, the Navy fell short of identifying other points of failed responsibility within the Naval chain of command. The Navys quick-to-judge tactic of blaming Commander Lloyd Bucher resulted in overwhelming public support for Bucher and his crew, and an embarrassment for the Navy. The action of the Navys assigning Commander Bucher to be its stalking horse fooled no one. The American public learned that a series of blunders on the part of the Navy and the Johnson administration had placed the Pueblo in a perilous situation, which was not Buchers doing. Lieutenant Commander William Armbruster, a Naval Intelligence Officer, writing for the Naval War College Review in 1971, examined the effect of public opinion on the Navys decision following the Pueblo Court of Inquiry and wrote, Public opinion has historically been a potent force to be reckoned with in American political history. He went on to write, The apparent public hostility during the Court of Inquiry was possibly a factor in determining final disposition by the Navy. He continued, Many, frustrated by the system, found it easy to identify with Commander Buchera helpless victim of an insensitive, unresponsive, military bureaucracy.

Foreign policy blunders were not confined to the Navy. The White House and Johnson cabinet, the National Security Agency (NSA), and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) all held the same short-sighted, misfocused view of international relations, that is, a belief that smaller communist nations could not act autonomously, but were instead, influenced by either the Soviet Union or China. This global misjudgment reflected a lack of cross-agency intelligence communication and poor leadership, thereby exacerbating an already embarrassing situation played out on the world stage. Following the Second World War and into the early part of the Cold War, the United States was the worlds most powerful nation. Yet, America, by the action of the North Koreans, learned a discomfiting lesson from an isolationist, autocratic country of lesser global significance. Members of the Johnson administration and the Navy were left wringing their hands as they weighed answers and responses to the

Next page