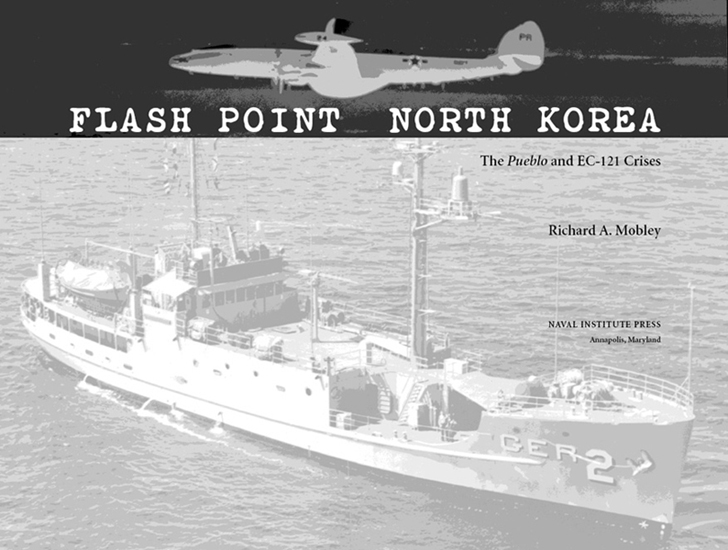

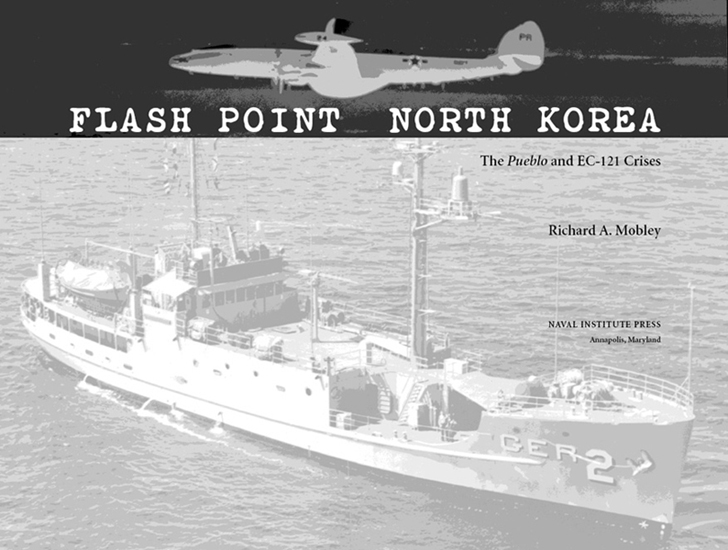

FLASH POINT NORTH KOREA

The latest edition of this book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2003 by Richard A. Mobley

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mobley, Richard A., 1952

Flash Point North Korea : the Pueblo and EC-121 crises / Richard A. Mobley.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61251-356-0

1. Pueblo Incident, 1968. 2. Military intelligenceUnited States. 3. Military surveillanceUnited States. 4. Korea (North)Foreign relationsUnited States. 5. United StatesForeign relationsKorea (North) 6. Korea (North)Military policy. I. Title.

VB231.U54M63 2003

358.4'5dc21

2003012358

10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

First printing

CONTENTS

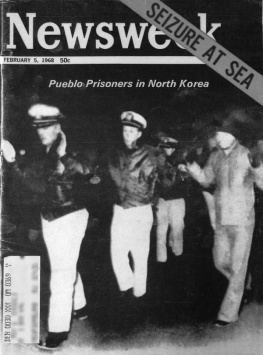

At first blush, the United States seemed blind and impotent in the late 1960s when it failed to either anticipate or retaliate for two related North Korean provocations. In 1968, the North seized USS Pueblo and held the crew for nearly a year of brutal mistreatment. The ship is still in North Korean hands. Less than four months after Pueblos crew returned to San Diego, thirty-one U.S. sailors and marines were killed when North Korean aircraft shot down an EC-121 reconnaissance aircraft some ninety miles off North Koreas east coast. Figuratively, lightning had struck twice; decision makers in Washington evidently had failed to learn anything from the first incident and seemed no better prepared for the second.

Yet, even contemporary press coverage and books published shortly after these events took place show that the United States was not as incompetent as it may have seemed. Contemporary statements suggest increasing concern at high levels about the growing threat. The United States was providing hundreds of millions of dollars of military assistance aid to help South Korea redress the military imbalance and was implementing a program to reduce North Korean infiltration. Moreover, within days of both incidents, the United States had marshaled sufficient striking power in the region to inflict major damage on the DPRK. It took high levels of professionalism, organizational ability, and planning to move, prepare, and sustain such forcesparticularly at a time when the Vietnam War was raging.

During the subsequent decades, questions about the performance of the national intelligence community and military planners lingered. Why were they surprised? Why were they unprepared? Why did they not retaliate (at least in the case of the EC-121 incident, when there were no prisoners whose lives had to be protected)? Answers to these questions began appearing in the 1990s when the U.S. government began releasing formerly top secret documents about these incidents as part of a normal declassification schedule. Other documents became available through Freedom of Information Act requests.

The new material paints a richly detailed picture of two dramatic national crises. When assembled chronologically and combined with subsequent accounts, the extensive collection of documents provides context for North Koreas behavior in the late 1960s and associated U.S. intelligence collection efforts against that nation. The documents afford insights into Pueblos mission and chronicle U.S. national- and theater-level responses during the first few days of the crisis. They also reveal the unpublicized role played by the military during the prolonged negotiations to free the crew and offer insights into lessons the U.S. Navy might have learned during the Pueblo crisis.

The hundreds of documents reveal profound concerns about North Korea and a determination to respond by collecting more intelligence about the North. They betray deep U.S. apprehension about the vulnerability of U.S. and ROK forces to surprise attack. They show how intensive National Security Council deliberations hammered out strategies for potential U.S. responses. They reveal the details of a wide range of retaliatory plans. They reveal resource strains. And they reveal an extensive effort to learn lessons and change the procedures for sensitive intelligence collection operations following these incidents.

Most Americans alive today have either forgotten about or never heard of the Pueblo incident, and fewer still recall the bloodier EC-121 shootdown. Even had no new evidence become available in the three decades since these incidents, the facts as they were known in 1969 would be fascinating. The raft of books written about Pueblo in the few years after the seizure still make for a good read. Perhaps the most fascinating contemporary document is the report of the Special Subcommittee on the USS Pueblo of the House Armed Services Committee. Entitled Inquiry into the USS Pueblo and EC-121 Incidents, the report rightly compares the two related events; it is the only lengthy public study to do so. The report is painful to read. Rightly or wrongly, the subcommittee spared virtually no one involved in the incidents. In both open and closed sessions, its members reviewed all aspects of both incidents, and its criticism was sweeping. Although one might challenge some of the subcommittees conclusions, individuals interested in studying or participating in complex, high-risk U.S. military contingency operations should scan the document. They will not find a dull page in it.

Even so many decades after the fact, the once highly restricted documents that have recently come to light conjure up the emotions of the crisisthe challenge of having to respond quickly when American lives were at stake. The documents are intriguing in themselves, but I had additional reasons for choosing to investigate the twin incidents. During my assignment at U.S. Forces Korea headquarters in Seoul during the late 1990s, I had firsthand experience with attempts to anticipate North Koreas behavior. I developed an appreciation of the difficulty of fashioning a realistic model for reasonable North Korean behavior and for anticipating North Korean provocations. The challenges of anticipating a surprise attackeven a very limited onewere sharply apparent at the command headquarters (just as they had been in the late 1960s).

This book stems from two articles I recently wrote. The Naval War College Review published Pueblo: A Retrospective in spring 2001, and the Naval Institute Proceedings published EC-121 Shootdown in August 2001. While enjoyable, the task of researching these incidents was a formidable one. Some of the documents were readily accessible in on-line sources or in the appropriate volume of the

Next page