Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2011 by Walter Earl Pittman

All rights reserved

Cover image by permission of Larry Pope. Photograph by Joe Arcure. All rights reserved.

First published 2011

Second printing 2011

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.329.9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pittman, Walter E.

New Mexico and the Civil War / Walter Earl Pittman.

p. cm.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-137-6

1. New Mexico--History--Civil War, 1861-1865. I. Title.

E522.P48 2011

978.904--dc22

2011014425

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Chapter 1

The New Mexico Territory in 1861

The New Mexico Territory in 1861, comprising the later states of Arizona and New Mexico, was a huge, sparsely populated region, far removed from any other American population center. In an area larger than the Deep South, it recorded only 93,516 inhabitants, mostly poor Hispano farmers and civilized Pueblo Indians living along the rivers, where water was available for agriculture. Most people lived near the Rio Grande, from Socorro north into Colorado. Around them was wilderness in all directions, peopled by large, warlike tribes who had depredated the settlers for centuries. There were Apaches to the south, Navajos to the west and Utes in the north, and on the Plains to the east roamed the bands of Comanches, Jicarilla Apaches and Kiowas.

Santa Fe, the capital city and largest town, was a dusty adobe village of 4,600 souls. Mesilla, at the southern end of the territory, was even more isolated and primitive and had only 2,600 inhabitants. Mesilla and the lower Rio Grande settlements were separated from the main centers of population, Albuquerque and Santa Fe, by some two hundred miles of inhospitable wilderness, including the dread Jornada del Muerto (Journey of Death), a dangerous desert passage. To the west was the large and even wilder land acquired from Mexico in the Gadsden Purchase. Only 2,421 people, civilized enough to be enumerated by the census taken, lived there. As in New Mexico, many of the Anglos were actually soldiers stationed at the numerous forts and camps scattered throughout the region. Most of the remainder lived in Tucson, in the mining center at Tubac near the Mexican border or in small farming or mining communities that were beginning to develop around army posts.

Most of the population of the territory (not counting the Indians) were Hispanic and of Mexican origin. Almost all had some degree of Indian ancestry. As a result of centuries of extreme isolation, most New Mexicans had little knowledge and even less interest in events in the larger world. The small number (two hundred families) of educated upper-class New Mexicans (the ricos or rich) looked to Mexico and Missouri for social, cultural and religious fashions. These wealthy New Mexicanslike the Armijo brothers, rich merchants who were the sons of the last Mexican governor of New Mexico, and Miguel A. Otero, the territorys representative to the U.S. Congresswere strongly pro-Southern in their political outlook. Indian slavery and debt peonage were widespread in New Mexico. Miguel A. Otero actively sought to align New Mexico with the South and pushed through a stringent slave code for the territory in 1859, although there were only a handful of black slaves in the immense territory. These Hispano grandees had tremendous influence among the poorer classes. Their leadership, as well as lingering resentments resulting from annexation of the territory in 1847 as a result of the Mexican-American War, created some lukewarm support for the soldiers of the Confederacy among the natives. It would not last, though.

In the fourteen years during which the United States had controlled the Southwest after taking it from Mexico, there had been constant warfare with the Navajos and Apaches. The U.S. Army was tasked to prevent the wild tribes from raiding Anglo and Hispano settlers, the civilized Pueblo tribes and the Mexicans in north Mexico, their primary source of livelihood. Historically, they made their living raiding the civilized tribes and settlers.

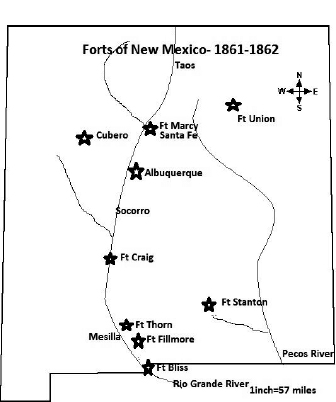

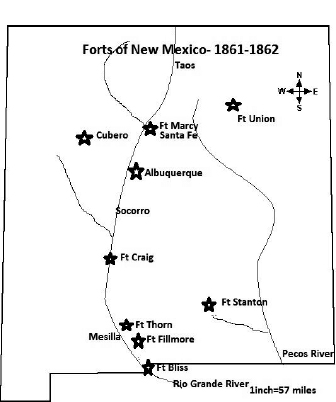

The almost endless campaigning by seriously undermanned military forces was centered on a string of forts stretching from San Antonio to Yuma, Arizona, and from Fort Union in northern New Mexico to Fort Buchanan in southern Arizona. Other forts were scattered in the Navajo country, where a larger war was being fought. Apache violence flared in 1860 and 1861, as attacks on white settlers and travelers increased in frequency, severity and duration.

There were several reasons for this outburst of Indian violence. When the hostilities of the Civil War commenced in 1861, the United States government quickly moved to concentrate its available military forces where they were needed most, in the East, and abandon the (now) less critical Indian campaigns in the West. In New Mexico and Arizona, this meant abandoning (and burning) the far-flung outposts like Forts Buchanan, Breckinridge, McLane and so on to allow the Regular forces stationed there to march east to join the big war. The small remaining Regular forces were to be concentrated at Santa Fe, Fort Union and Fort Craig. In reality, because of the Confederate invasion and the Indian attacks, far fewer troops could be sent east than the government had planned. Watching from their wilderness outposts, the hostile Indians saw the withdrawal of the troops as a victory, and recognizing the relative weakness of the army, they were quick to strike the exposed settlements.

Forts of New Mexico, 1861.

Stationed at the army forts scattered across the New Mexico Territorys plains, deserts and mountains were about 2,600 men in mid-1861. Many of these marched east, but most remained and were reinforced with newly raised volunteer units from New Mexico and Colorado. By the end of 1861, 5,646 Union soldiers were under arms, and by mid-1862, there were more than 7,000. Their commander was Colonel E.R.S. Canby, a cautious, realistic and prudent infantryman who would succeed in destroying a Confederate army without winning a battle. In the process, he acquired a reputation as a chivalric and gentlemanly warrior unmatched by any other Union officer. He rose to command when his two superior officers in the Department of New Mexico resigned to join the Confederacy. One, Colonel Henry H.H. Sibley, would soon return to New Mexico at the head of an invading army of Texans.

Chapter 2

High Times for Dixie

When General Henry Sibley went to Richmond to offer his services to the Confederacy, he left behind him in New Mexico weak and demoralized Union forces. Scattered in small posts across the barren landscape, the troops had not been paid for months; received poor and inadequate rations, clothing and equipment; and were dispirited by the defections of their officers to the Confederacy. Observing this as he traveled south and east from Fort Union to San Antonio, Henry Sibley began to dream a big dream. New Mexico was weakly held, he believed; it could be seized almost without a struggle. And New Mexico was the key to the whole Southwest: the gold fields of Colorado, Arizona and sparsely populated northern Mexicoand then California. It was the dream of a Confederate empire stretching from sea to sea that Sibley took with him to Richmond to lay before his old friend, Jefferson Davis. It could be done, Sibley believed, almost without cost. The Rebels could live on captured supplies stockpiled in the numerous forts. Sibley returned to Texas in July 1861, with a commission as brigadier general and the authority to raise an army to invade New Mexico.

Next page