For Sheena

(Long may we run)

CONTENTS

Guide

A Celtic cross marks the birthplace of Saint Columba in County Donegal, Ireland.

In 563, Columba founded a monastery on the Scottish island of Iona, and from there promulgated a literate, Celtic-Christian culture that turned the Irish and the Scots into one people.

N ot long ago, while driving with friends in Newfoundland, an Irishman heard a local man caution a third party against stepping out of a car into traffic: Dont get out on the Ballyhack side. The Irish visitor, astounded, asked the Newfoundlander to explain. The man said the expression meant, Dont get out on the right. But he had no idea why it meant that or where it came from.

The Irishman, who hailed from New Ross in County Wexford, told him that, for someone travelling the short distance south from his hometown to the coast, the village of Ballyhack lies to the right. Not only that, but the Irishman could account for how the expression had crossed the ocean: generations of fishermen had sailed from New Ross to fish for cod off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

The man who told me this anecdote, Patrick Grennan, shares an ancestor with former American president John F. Kennedy. Grennan has developed the original Kennedy Homestead, just outside New Ross, into a tourist attraction. The town itself is home to 8,200 people, and also to the Dunbrody Famine Ship, an authentic reproduction of one of the coffin ships that, in the late 1840s, carried at least 1 million immigrantssome say as many as 2.5 millionto North America.

We had gravitated to New Rossmy wife, Sheena, and Iduring one of several rambles around Ireland and Scotland. Having tracked my Scottish Protestant forebears to the Isle of Gigha, and written about that in How the Scots Invented Canada, I was on the trail of my Irish Catholic ancestors. One of them, Michael Byrne, had been born in New Ross in 1825two years after JFKs ancestor Patrick Kennedy. As boys, they must have known each other.

A week or so after visiting New Ross, north up the coast in County Mayo, we visited Westport House, a spectacular country estate built in the 1700s on the site of an ancient castle. We chatted with a staffer in his early twenties who asked if we had any ancestors from Ireland. I said yes: A man named Byrne, born in New Ross in 1825.

He said, My name is Byrne.

My ancestors first name was Michael.

Thats my name, he said. Michael Byrne.

The father of my immigrant ancestor was named Patrick.

My fathers name is Patrick.

I squinted at him: Youre too young to be my ancestor.

Who doesnt love a coincidence? On the other hand, Byrne is the sixth most common surname in Ireland. And a cursory glance at any database of emigrants reveals a jungle of Byrnes named Michael and Patrick. Still, this serendipity made me feel at home, and pointed up the enduring nature of Canadas connections with Ireland.

North Americans in search of their roots quickly realize that an ocean is an artificial barrier. Thanks to advances in digital technology, we cross the water and go back as far as we can: five generations, seven generations, nine. We trace our personal stories to people who lived centuries ago in County Kerry, Kintyre, the Aran Islands. As genealogists, we revel in these discoveries.

Canadian intellectuals tend to fail here. Instead of voyaging with genealogists, who navigate through time and space, they hunker down with geographers and sociologists. They assume geographys limitations and cease investigating our collective past at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. The end result can only be one-dimensional, paper-thina survey of the present. For meaning, substance, depth, and a sense of direction, you need history... or what I think of as cultural genealogy. Despite our perpetual obsession with our collective identity, we Canadians have never investigated the demographic reality that informs this bookthe fact that more than nine million Canadians claim Scottish or Irish ancestry. Did the ancestors of more than one-quarter of our population arrive without cultural baggage? No history, no values, no vision?

Surely the idea is ridiculous. Canada is not just a geographical land mass. It is a cultural, political, and economic entity. It is a complex web of interconnected governments, businesses, institutions, organizations, and individualsan interweaving of social, cultural, and communications networks. Canada is a multi-dimensional creation. To the east, Canadian geography finishes at the Atlantic Ocean. But this nations history crosses that ocean. And it does so more often to Scotland and Ireland than to anywhere else.

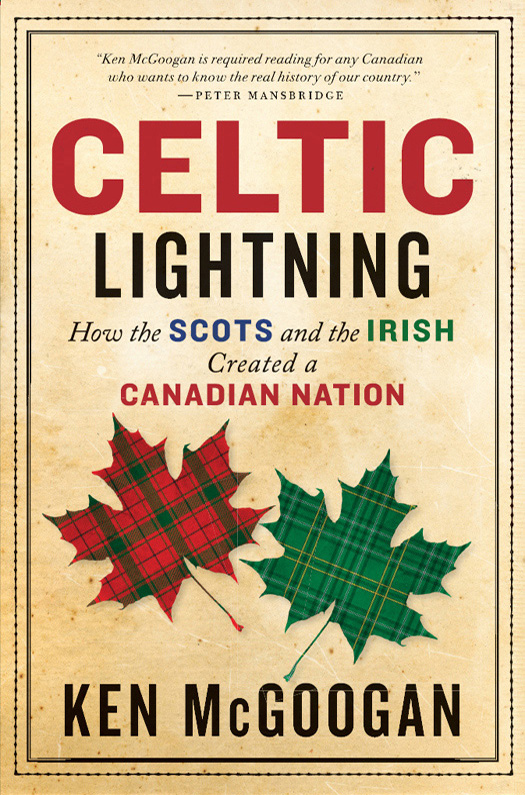

Look at the numbers. Canadas population recently exceeded 35 million. But in 2011, out of 32.8 million citizens, Statistics Canada reported 4.7 million Canadians (14.3 per cent) claiming Scottish ancestry, and 4.5 million (13.7 per cent) citing Irish. Those of Scottish and Irish heritage, taken together, constitute the largest minority of Canadians: 28 per cent. That compares with 19.8 per cent English and 15.2 per cent French. Even if a couple of million Scottish and Irish claims overlap, Celtic Canadians represent the largest cultural aggregation in the country. These numbers suggest that the Scots and the Irish, many of whom arrived relatively early, must have strongly influenced the shaping of multi-dimensional Canada.

Purists will argue that the two national narratives, the Scottish and the Irish, should properly remain separate. But fifteen hundred years ago, the Irish and the Scots constituted a single people. They were Gaelic-speaking Celts, citizens of the same maritime sphere. They plied regularly between Scotland and Ireland. The arrival of the Vikings, and their eventual integration, only enhanced the turbulent coherence of that seafaring world. By the 1100s, after three centuries of Scandinavian immigration and influence, that maritime culture had become Norse-Gaelic.

Not until the 1100s, when the Anglo-Normans invaded both countries, did the Scots and the Irish begin fighting separate battles for survival. Over the centuries, despite constant interaction, the two related peoples developed distinct national epics, different parades of warriors, scholars, adventurers, pirate queens, and revolutionaries.

But as a Canadian whose ancestors include both Scottish Protestants and Irish Catholics, I perceive in the two traditions more commonalities than differences. In fact, I see a single braided narrative celebrating the same bedrock values. In this book, to encompass that dual history, I use the word Celtic in its popular sense, to embrace all things Scottish and Irish. Lightning strikes when the two electrically charged traditions come into contact.

Returning to cultural genealogy, I would draw your attention to a work that surfaced on the New York Times list of the one hundred most significant books of 2014: The Invisible History of the Human Race: How DNA and History Shape Our Identities and Our Futures. Author Christine Kenneally argues that until recently, no one has ever tried to systematically measure whether and how culture is transmitted from one generation to another and, if indeed it is, to determine for how many generations it is passed along.