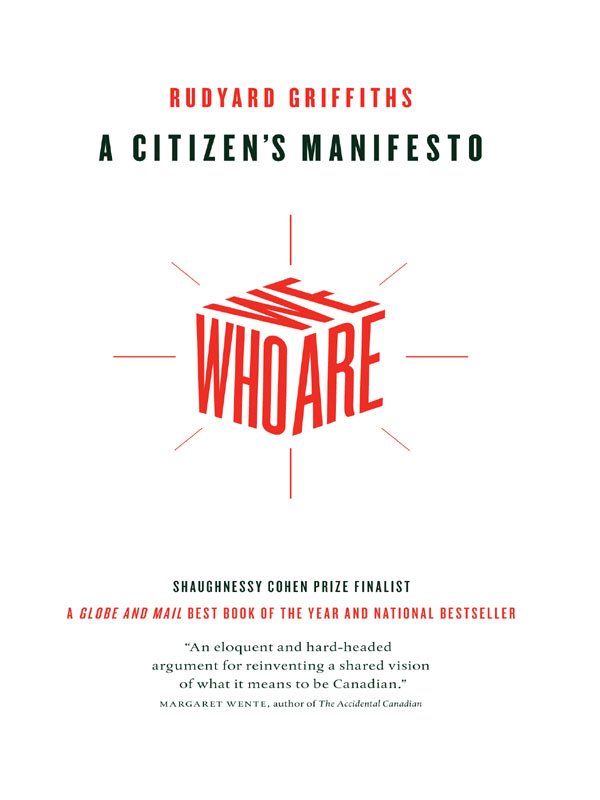

WHO WE ARE

WHO WE

ARE

A CITIZENS MANIFESTO

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS

Douglas & McIntyre

D&M PUBLISHERS INC.

VANCOUVER / TORONTO

Copyright 2009 by Rudyard Griffiths

09 10 11 12 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from

The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

A division of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.dmpibooks.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Griffiths, Rudyard

Who we are : a citizens manifesto / Rudyard Griffiths.

ISBN 978-1-55365-124-6

1. National characteristics, Canadian. 2. Canada Social conditions 21st century. 3. CanadaEconomic conditions21st century. 4. Canada Politics and government 21st century. I. Title.

FC97.G74 2009 971 C2008-907598-6

Jacket design by Naomi MacDougall

Text design and typesetting by Ingrid Paulson

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free paper that is forest friendly (100% post-consumer recycled paper)

and has been processed chlorine free

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

This book is dedicated to my grandfather,

Group Captain John Francis Griffiths, DFC

July 21, 1905May 9, 1945

| CONTENTS

ALONG with many Canadians in their thirties, my political coming of age did not coincide with the tumultuous 1988 free-trade election, the failures of the Meech Lake or Charlottetown accords or the fall of the Berlin Wall. These events, momentous as they were, seemed driven by the politics and personalities of my parents era. The crisis that shook me out of the comfortable What, me worry? complacency of adolescence and taught my generation an object lesson in why politics matter was the 1995 Quebec referendum.

The nail-biting drama that unfolded on television screens across the country on that late October evening and the emotional living-room debates that accompanied it seared into my consciousness the precariousness of this project we call Canada. Despite the history we might share or the values we might believe unite us as Canadians, during those anxiety-filled hours the countrys continuing existence was measured in mere fractions of a percentage pointa surreal, if not sad, calculation of the sum of our nationhood.

In the aftermath of the referendum and in light of the razor-thin victory eked out by the No side, two friends and I decided to do something. To bottle up and ignore the passion that had filled and fuelled the weeks leading up to the final vote seemed to us a capitulation to the very phenomenon that had landed the country in such a mess in the first place, namely our indifference to the common history, enduring values and civic traditions that bind Canadians together, French and English, Aboriginal and immigrant.

Without a scintilla of experience or two sous to rub together, Michael Chong, Erik Penz and I, all in our mid-twenties and freshly out of university, set about the work of launching the Dominion Institute. Our goal was to create an organization that would show Canadians that the countrys continued existence should not be presented primarily as an economic proposition or necessity, as so many business and political leaders had argued in the run-up to the referendum. Rather, the Institute would advance the idea that the foundations of our unity should rest, first and foremost, on a deep appreciation and knowledge of the countrys past, its enduring civic traditions and the struggles of previous generations to forge an inspiring civic identity capable of bridging our ethnic, regional and linguistic differences in common purpose.

This lofty vision survived to see the light of day thanks to the financial and moral support that followed the official launch of the Institute on Canada Day 1997, when we released the first of many polls that revealed how little Canadians know about their countrys history. Our initial splash in the media and a two-year grant from the Donner Canadian Foundation saw the Institute through a challenging start-up period of missed payrolls, bounced rent cheques and a professional staff of only two, myself included. But sure enough, our message about the importance of Canadian history and shared citizenship to the countrys future won adherents, and the DI became a going concern.

Leading the Institute was an exercise in guerrilla-style public advocacy. We put Louis Riel on trial on the cbc and drew three-quarters of a million viewers in Quebec and English Canada and a raft of Mtis protesters. We launched a veterans speakers bureau that has helped some 3,000 servicemen and women share their life experiences with upwards of a million school children. We used the media shamelessly (for a decade, the Institute generated, on average, a news story a day) to get our message out. We published books, produced television documentaries and text messaging campaigns, invested in feature films and commissioned a steady stream of public opinion polls. By the time I stepped down as full-time executive director in 2008, we had raised close to $20 million in support of our mandate, employed dozens of committed young people and created a network of 3, 700 volunteers who continue to champion the cause of civic literacy in schools and local communities nationwide.

In short, the Institute succeeded beyond our wildest expectations. It redeemed our faith in the relevance of Canadas past and civic traditions to the countrys future and restored our conviction that the ties that bind us together are stronger than the forces that would pull us apart.

Our sense of accomplishment aside, when I finally handed over the reins of the Institute I could not help feeling that I was leaving a job half finished. I felt this way because during my final years at the Institute we found ourselves coming up more and more frequently against a view of the countrys nature and purpose that was very different from the pan-Canadian philosophy we espoused.

Whether it was our advocacy for more and better history and civics education in the schools or our belief in the centrality of Canadas bicultural foundations to present-day debates about the countrys values and institutions, our detractorswithin government, academia and some mediatook issue with our most basic premises. These critics, many of whom held positions of influence and power, openly questioned the merits of maintaining, let alone nurturing, a strong national identity based on shared institutions, deeply felt social obligations and widely held civic values.

At conferences, in books and op-ed pieces and through their own advocacy groups, our antagonists contended that Canada had entered a new phase in its development, a period in which the multiple loyalties and strong regional identities that have always been constants in CanadaFrench vs. English, Central Canada vs. the West and Atlantic Canada, for examplewere being accentuated by the effects of globalization, within and beyond our borders. As a result, the work of the Institute and similar groups to promote a common Canadian identity supposedly risked unsettling the uneasy peace between the countrys regions, its historic minority groups and its national government and institutions.According to this line of reasoning, the Institutes efforts to assert a common civic creed in our schools and popular culture also threaten the fuzzy and indeterminate nature of what it means to be Canadian today, the much-vaunted national trait that allegedly allows us to thrive as a country comprised of disparate regions, peoples and groups who embrace a myriad of allegiances, ancestries and far-flung homelands. These are not just the views of an academic fringe. One in three Canadians surveyed by the Institute in a nationwide poll in 2007 stated that part of what makes Canada a successful society is the

Next page