Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by David E. Casto

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.560.3

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.107.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Preface

In the early 1900s, my grandfather James Casto and his family left their northern Pope County, Arkansas farmstead to sharecrop in another part of the state. Along with James were his parents, David and Salina Casto. At some unknown locale, old David, a Union war veteran, began to recognize the countryside. Something jogged his memory; perhaps a particular farmhouse or a curve in the road looked familiar. When the group stopped to have their lunch by the roadside, the old man told them about a fight his regiment had been involved in during the war. After the action, the Rebels had retreated, leaving behind some wagons full of gunpowder and provisions. Not to be encumbered by their newly acquired spoils, the Union horsemen parked the Rebel wagons on a pond bank, loaded them with enemy rifles and saddleswhatever they couldnt carryand set them afire. They pushed the wagons into the shallow water and threw the gunpowder onto the blazing heaps. The ensuing explosion ripped through the treetops, blowing mud and water everywhere. Sure that they were in the vicinity of the pond, the old man asked my grandfather to drive him around. Leaving the women and children to rest by the roadside, James and his father took off to look for the pond where the soldiers had burned the wagons years before. They spent the rest of the afternoon in a fruitless search. Too much land had been cleared and farmed over; too many years had passed for the old man to remember the exact place. The men eventually gathered up the family and traveled on, the old soldier much disappointed.

When I was a child, Grandpa and Grandma Casto were old folks, well into their eighties. They lived on a farm south of Atkins in an old house that didnt have running water. A good part of my childhood was spent on that farm. My grandparents always talked and told stories, and as a youngster I was familiar with the names, deeds and misdeeds of various relatives and allied families. They would invariably talk about their parents, and the biggest event in their parents lives had been the Civil War. They could tell me only bits and pieces of stories their parents had handed down to them. My grandpa said his pap, as he called his father, had ridden a swift black mare and had once jumped a ditch alongside a Rebel soldier, knocking him off his horse and taking him prisoner. He said his father had served under a general named Carr, the name spoken in a tone that denoted the generals importance. My grandparents said that cannon fire from a distant battlefield could be heard miles away, so loud it rattled the walls of my great-grandma Salinas home with each shot. From Grandma Casto, I knew that her mother and grandmother in northern Pope County had lived in fear of the dreaded bushwhackers. These outlaws, who avoided service in either army, preyed on the women and children left at home. With anger in her old voice, she described these brigands ripping the floorboards out of her grandparents house to steal whatever meager belongings or food they had hidden away. Finding only a tub of cornmeal, they filled their saddlebags, dumping out the rest into the dirt for their horses. My grandparents didnt know or tell much else, but it was enough to fire my imagination.

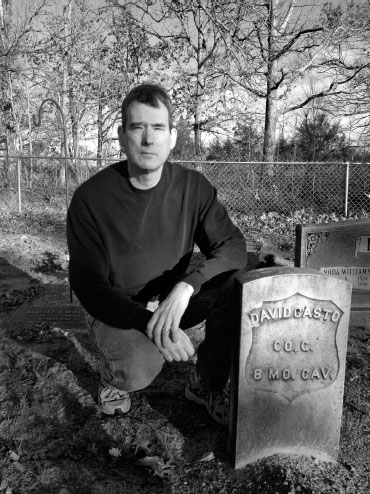

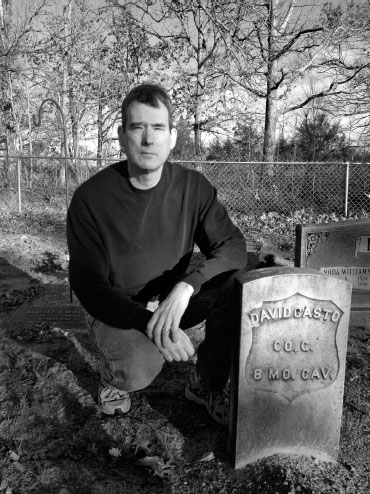

These fragments of stories that were handed down fueled an interest in the war, and my familys part in it, that has never diminished. At cemetery decorations in Tilly, Arkansas, I saw the old government-issue tombstone that read, David Casto, Company G. 8 Mo. Cav., and I wanted to know more about this man, this soldier, whose name I bore. As I got older, I did more research to try and learn more about my ancestors war but was unsatisfied with what I found. While the 8th Missouri served the whole war in the Trans-Mississippi, there was only scant mention of it in campaign or battle books dealing with that department. It was on the sidelines at the Prairie Grove battle, and almost nothing had been written about the campaign to take Little Rock, in which it had taken part. The 8th wasnt at the Battles of Arkansas Post or Helena. It didnt take part in the Camden Expedition or battles at Poison Springs, Marks Mill or Jenkins Ferry. It didnt take part in the campaign against Sterling Price when he invaded Missouri for the last time. It didnt help matters when I received my ancestors service file from the National Archives. David Castos service and pension records were so dry and devoid of information that actually dealt with the war that for all I could tell he had pulled a long hitch of guard duty. Years later, through the many volumes of the Official Records, followed by a trip to Salt Lake City, where I found the 8th Missouris regimental returns and roster, I began to find what I had been looking for.

The author at his great-grandfathers grave in the Union Hill Cemetery, Tilly, Arkansas. Photo by author.

This book begins in the spring of 1864 for a couple of reasons. My ancestor joined the regiment at that time, but it also marked an upturn in activity in Arkansas that in my mind has been largely understudied, especially from the Union perspective. What I had initially thought of as a long period of relative inactivity was actually quite different. I realized I should do something with the material I was gathering, so I set out to write a book about this regiment of Missouri farm boys and their role in the war.

My great-grandfathers part in the war probably started like many others in southwest Missouri. Although born in Arkansas, David Casto was raised on his familys Barry County, Missouri homestead, where he worked the farm and helped tend his fathers blacksmith shop. When war broke out in 1861, David was a young teenager. That portion of the state was divided in loyalties right down to the township and neighborhood levels. The Castos were Union people, and Davids father and two oldest brothers were members of a Home Guard company. In the summer of 61, when the Union army was defeated at Wilsons Creek, southwest Missouri was abandoned to the Confederates. Realizing that he and his family were in an increasingly dangerous situation, the elder Casto loaded up his family and fled to Fort Scott, Kansas. Once there, the two oldest sons joined the 6th Kansas Cavalry.

In the spring of 1862, southwest Missouri once again came under Union control. The Castos moved to the Wilsons Creek area to be near the protection of the garrison at Springfield. Davids father joined the 72nd Enrolled Militia Regiment and took part in the defense of the city in January 1863, when Rebel forces under General John Marmaduke raided Missouri. In December of that year, David turned seventeen. There was a recruiting party for the 8th Missouri Cavalry in Springfield, and the youngster didnt waste any time putting his X on the line and taking the oath. Like his father, two older brothers and two brothers-in-law, young David Casto would fight for the Union. Here is the story of what he and his comrades in the 8th Missouri experienced during the last fifteen months of the war.

Next page