Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Kevin R. Pawlak and Dan Welch

All rights reserved

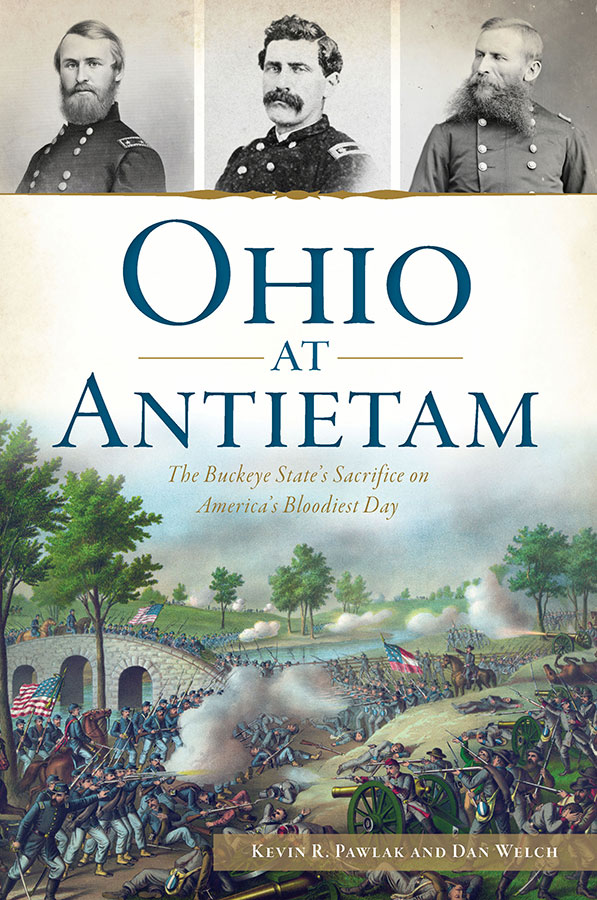

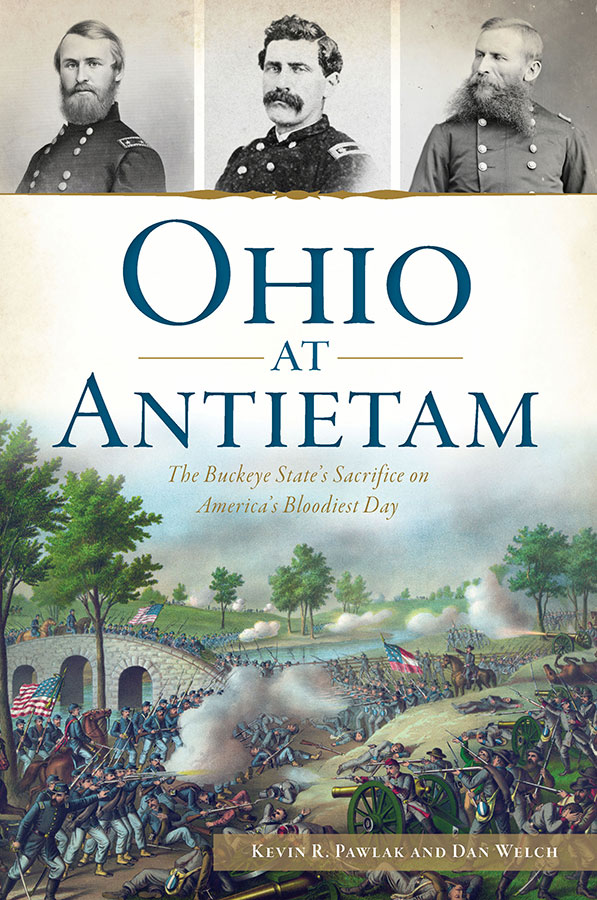

Battle of Antietam, by Kurz and Allison, 1888. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

First published 2021

E-Book edition 2021

ISBN 978.1.43967.328.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938394

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46714.691.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Ohios soldiers who served in the Maryland Campaign.

Not for themselves, but for their country.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We first wish to sincerely thank our editor at The History Press, John Rodrigue. John graciously guided us through the ups and downs of writing this book. Researching and acquiring images during the pandemic was not an easy task. John was always willing to be flexible with us and lend a helping hand. Ashley Hill, likewise, offered helpful comments to improve the manuscript.

Many people kindly gave us their time to help make this book possible. Edward Alexander created the maps depicting the actions of Ohioans at South Mountain and Antietam. Tom Clemens provided sources and help along the way. Specifically, he helped answer the question about where Ewings brigade crossed Antietam Creek on September 17, 1862. Steve Stotelmyer, likewise, lent us assistance.

A host of people and organizations have preserved the stories of Ohioans during the Maryland Campaign. Julie Mayle and the staff at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library digitized many previously unpublished images for this book. Jenni Salamon and the staff at the Ohio Historical Society provided images of the battle flags found in this book. Jon Tracey braved a cold winters day to take photographs of headstones in Antietam National Cemetery. Leight Murray of Marietta, Ohio, took numerous modern-day images of notable Ohioans homes and the final resting places of those who served at Antietam. Larry Strayer agreed to provide a hard-to-find image of Melvin Clarke, an image and story crucial to the manuscript. Mike Peters of Pickerington, Ohio, provided digitized versions of several hard to find primary sources. Mike also put us in touch with several other private collectors, thereby expanding the visual aspects of this work. Ron Davidson at the Sandusky Library also provided another crucial image that was necessary to give a face to an important story in the manuscript. Linda Showalter at Marietta College aided us in conducting research and digitizing images. Stephanie Gray at Antietam National Battlefield was always willing to let us research in the parks library. Jennifer Loredo at the United States Army Heritage and Education Center supplied us with images from the indispensable MOLLUS Collection.

Though many people pushed this book across the finish line to the printers, any mistakes or errors are entirely our own.

Lastly, we could not have written this book without the Ohioans who participated in the Maryland Campaign and extensively wrote about their experiences. It is to them that we dedicate this book. Without their efforts to preserve and share what they saw, felt and thought in September 1862, this book would have been impossible to write.

INTRODUCTION

The federal war effort during the American Civil War was truly a united endeavor. It was a geographic collective of states that believed in the preservation of the Union, the end of slavery and the need to suppress an open rebellion within the country. States as far away from each other as Maine and Wisconsin, Rhode Island and Minnesota, all came together to accomplish the strategic and ideological goals of the United States government between 1861 and 1865. The state of Ohio was among those states willing to offer its men, material and money to this effortand it was one of the earliest to do so.

On January 7, 1861, just two and a half weeks after South Carolina declared its secession from the United States, the Ohio General Assembly met and loudly proclaimed the states feelings toward rebellion, secession and war. State senator Richard A. Harrison offered a number of resolutions that were then adopted by both houses of the state legislature. These resolutions noted, in part: The people of Ohio believe [in] the preservation of this government and that the general government cannot permit the secession of any state without violating the bond and compact of the Union. Furthermore, they stated, The power of the national government must be maintained. Despite these early proclamations from the Ohio legislature positioning the state in the then-current sectional crisis, there were still aspects of the southern states constitutional and political ideologies that Ohio still agreed with.

The people of Ohio are opposed to meddling with the internal affairs of other states, the resolution stated. Thus, these Ohio state congressmen believed in the concept of states rights and Ohios desire not to interfere. Furthermore, one of the resolutions went so far as to support the Fugitive Slave Law and the repeal of any state laws that had been passed in opposition to it being carried out by those states citizens. These parts of the resolution horrified the numerous abolitionists within the state. Even though these aspects did not align with all of the northern states political and constitutional ideologies, as the secession crisis moved further into the winter of 1861, the Ohio state legislature felt strongly about what it had passed. Copies were sent out to President Buchanan, both the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate and even the governors of all the states that were still in the Union.

Although Ohio came out strong against South Carolina quickly after its secession ordinance, that did not mean it wanted to send its sons into battle if it could be avoided. When the Virginia legislature sent out a call for a peace convention in Washington, D.C., the Ohio General Assembly sent seven prominent Ohioians to the meeting on February 4, 1861. The conference ended in failure. And events continued to hurdle rapidly toward war. On April 12, 1861, an Ohio state senator rushed into the chamber. After catching his breath, he yelled out, Mr. President, the telegraph announces that the secessionists are bombarding Fort Sumter! The chamber fell silent. Abby Kelley Foster, an abolitionist who was in the gallery that day to hear arguments on the expansion of legal rights of married women, cried out, Thank God! It was not long before news of Fort Sumters surrender reached the chamber, and on April 15, President Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers. Governor William Dennison immediately asked President Lincoln what Ohios quota would be of that number. What proportion of the 75,000 militia you call do you give Ohio? Dennison wrote. We will furnish the largest number you will receive. Great rejoicing here over your proclamation. Ohios quota was 13,000 men. Overnight, Ohio transformed onto a war footing.

Within twenty-four hours of Lincolns call, the state appropriated $1 million to arm and equip these men and prepare for a defense. Soon, another $1.5 million was set aside in case of an invasion into the state. In addition to these funds, a tax was voted in the affirmative with the express purpose of providing economic relief to families of those men who volunteered for service. If this sum of money being spent on the new war effort astonished Ohioians in April 1861, it would prove to be just a miniscule amount of the total spent by April 1865 and beyond.

Next page