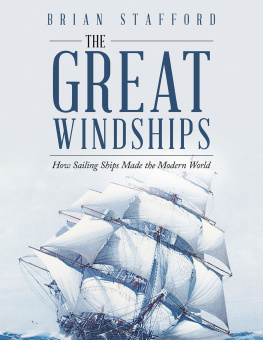

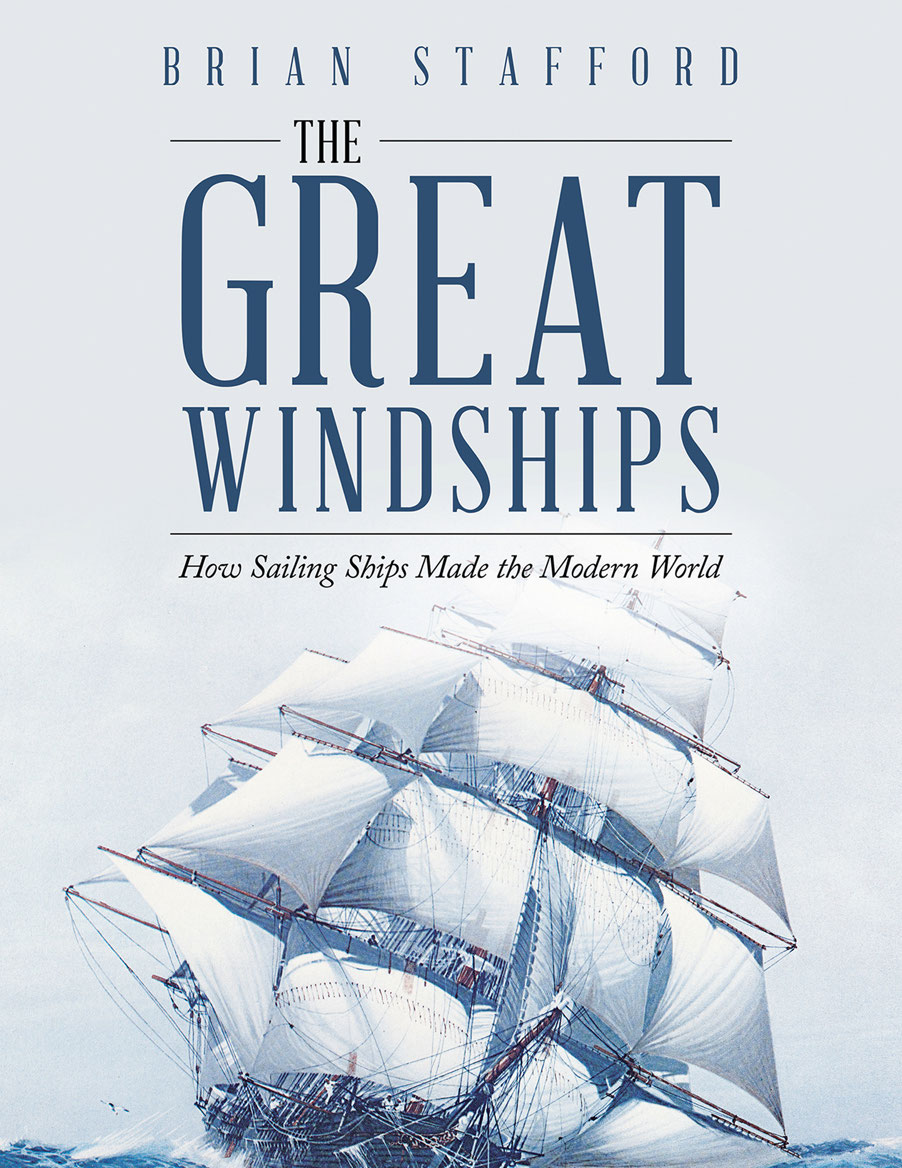

Copyright 2022 by Brian Stafford. 834200

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022907694

Rev. date: 08/30/2022

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

SuperiorAn Early (1822) Black Ball Line Packet

The Falls of Clyde

I magine it is 1938. You are standing on Point Spencer at the mouth of the Spencer Gulf on the southern coast of Australia. The weather is fine, with a strong breeze fetching up from the south.

Over the horizon, a tiny white rectangle appears, a tall obelisk of pale canvas, a panoply of sails emerging tier by tier. Below the sails, you see a small dark rectangle. Slowly, it reveals itself to be the sturdy riveted steel hull of a big four-masted barque.

The vessel is the great windjammer Moshulu, operated by the Finnish sailor and shipowner, Gustaf Erikson. She has sailed all the way from London to load almost 5,000 tons of grain from the wheat fields of South Australia at Port Lincoln, further up the gulf. In ten days time, she will make the ninety-one-day return voyage to Great Britain.

From her deck to the top of her mainmast, Moshulu measures 185 feet, equal to thirteen London double-decker buses stacked one on top of another. She is six cricket pitches long. Empty, she displaces (weighs) 1,700 tons, but her hold, which makes up most of the ship, can accommodate 5,300 tons of cargo, a ratio of over 3:1.

On board Moshulu on this particular voyage is apprentice seaman Eric Newby. He will later immortalise the barque in his 1956 book The Last Grain Race.

Moshulus trip to Australia covered over 13,000 nautical miles (around 21,000 kilometres) of wild, open, and trackless ocean. Except for the creaking of spars and the rush of water away from her brave bow, her journey from London has been silent. She has used only wind and ocean currents, the muscle and sinew of hardy souls that man her, and the seamanship of her master and mate.

Once her hull is packed with jute sacks of golden grain, she will retrace her path to the mouth of the gulf before facing the Roaring Forties. The ocean highway that brought her here will push her further south on a great circle path down to the fearsome fifty-plus latitudes. There she will sail much of the more than 15,000-nautical-mile track home.

On the way, she must round Cape Hornthe only milestone of her homeward journeyand traverse the fearsome maelstrom between South America and Antarctica. Cape Horn is a choke point pressured by the perpetual westerly winds that characterise the very south of the globe. An enormous volume of water is forced into a space only 400 miles wide, causing mountainous seas driven by the unabating wind. Sometimes, the situation is exacerbated by turbulent cyclones bulleting down off the Andes. Once through this dreadful gateway to another ocean, Moshulu will enjoy a relatively easy run for the remaining 5,000 miles of her voyage north up the Atlantic.

By the time she docks in Liverpool, she will have travelled over 28,000 nautical miles, considerably more than the circumference of the globe. She will also have brought back enough food to sustain thousands of people for many months. Other than the provisions for her crew and minor maintenance stores, she will have consumed nothing.

Certainly no non-renewable resources.

Built by William Hamilton & Co. in Glasgow in 1904 for the nitrate trade, Moshulu entered the great age of merchant sail in its twilight years. Her original name was Kurt after the principal of Siemers & Co., a Hamburg shipping company.

Kurt just happened to be in a United States port when it entered the First World War in April 1917. She was commandeered and given the American Indian name Moshulu, reputedly by the wife of Woodrow Wilson, the US president at the time. After the war, she was bought for a song and carried timber from the US west coast to Australia. By 1935, having passed through many hands, she had been acquired by Gustav Erikson, and it was under his flag that she made this voyage to Australia. A native of the land Islands off Sweden, Erikson had crewed or managed sailing ships all his life. He loved sail and was determined to keep the great windjammers working.

In 1940, Moshulu was seized by the German government. But her sailing days were over, and she would be used mainly as a storage hulk until she was rescued by an American dining chain and rerigged.

Today, she is a floating restaurant at Penns Landing in the US state of Philadelphia.

With no space required for engines or fuel, the barque is an example of perhaps the most efficient transport device ever conceived by humans. She is the result of centuries of continuous development, from the fragile caravels that first ventured out through the Straits of Gibraltar to the great windjammers that no distance or sea condition on earth could daunt.

Countless sailing ships have been turned into museums, youth hostels, training vessels, and restaurants over the years. No national celebration is complete without a parade of tall ships. Modern society finds romance in these vessels and reveres them. Unconsciously, perhaps, we pay homage to their gallant history and the contribution they made to the modern age. Form has followed function to create an object of beauty and environmental efficiency. This book is an attempt to trace their developmentand how world history moulded that process over half a millennium.

Source: From an original oil painting by Robert Carter OAM, Moshulu in the South East Trades

They mark our passage as a race of men,

Earth will not see such ships as these again.

John Masefield

T o better understand the following chapters in this book, a basic explanation of some concepts integral to sailing ship operation and development might be helpfulfor example, how they are measured, navigated, and rigged; their strengths and limitations; and a little about the defining form, whats known as the fully rigged ship. If the reader is more interested in the story of the great windships, then this chapter can be ignored or perhaps returned to later.

Most historians believe that hand paddlingpossibly while lying or sitting on a logwas the first means we adopted to move across the water. Our relationship with wood and water has evolved over millennia, to the point where it might be said to have entered our DNA. In time, iron, then steel (and later aluminium and various forms of advanced plastic) surpassed the use of wood. Wood has largely disappeared from the merchant marine, though our affinity with the material remains in the construction and restoration of wooden vessels for recreational and craft purposes.