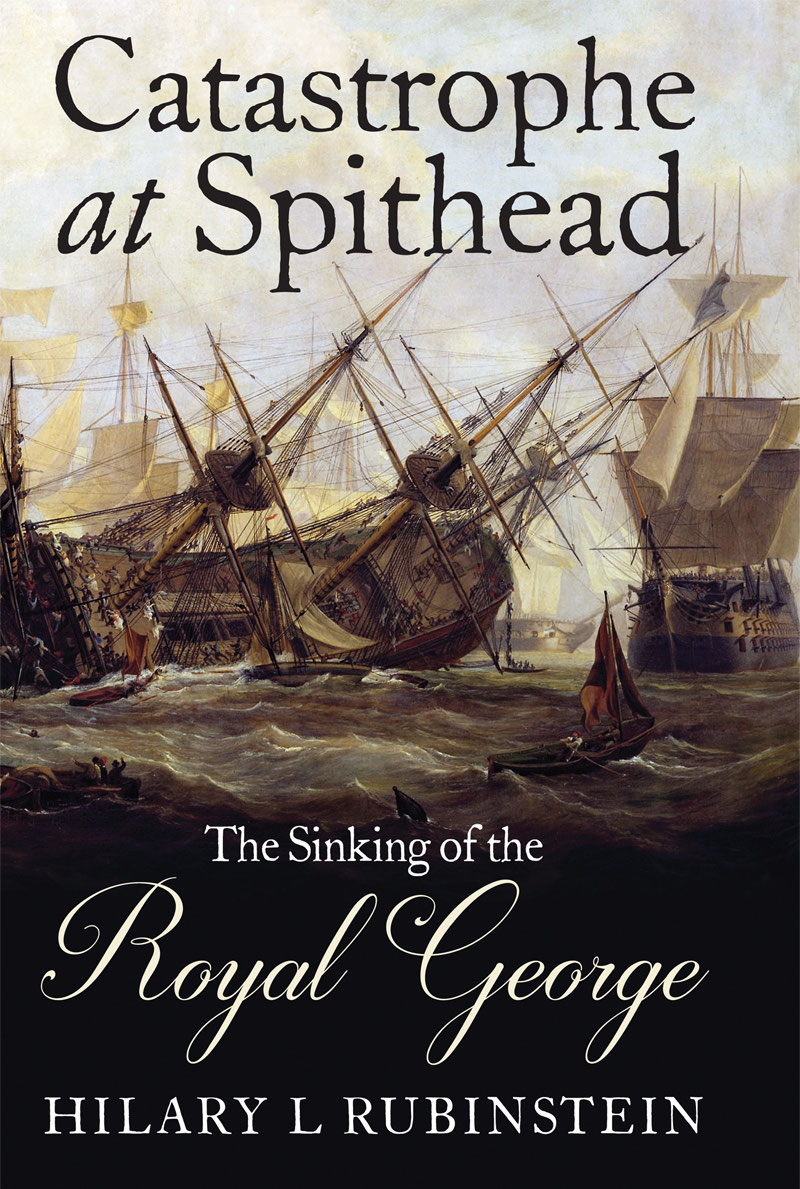

CATASTROPHE AT SPITHEAD

Catastrophe at Spithead

The sinking of the

Royal George

HILARY L RUBINSTEIN

Copyright Hilary L Rubinstein 2020

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Seaforth Publishing,

A division of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5267 6499 7 (HARDBACK)

ISBN 978 1 5267 6500 0 (EPUB)

ISBN 978 1 5267 6501 7 (KINDLE)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Hilary L Rubinstein to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt was one of the Royal Navys outstanding figures. A much-voyaged master tactician, he applied his clever scientific mind to improvements within the naval service notably devising a flexible numerical signal code, which by enabling more fluent communication between ships at sea reduced the likelihood of fleet commanders intentions being misunderstood. The legacy of his labours informed manoeuvres during the conflicts with Revolutionary France and Napoleon.

Kempenfelt sailed through dangerous waters, some unreliably charted, to the other side of the world and back. In one of the most sensational and puzzling incidents in naval history, he drowned along with most of his crew and their many civilian visitors, male and female, one summer morning in a familiar English anchorage. This work examines that tragedy, the sudden capsizing at Spithead on 29 August 1782 of Kempenfelts mighty flagship HMS Royal George. It discusses such issues as how and why she sank; on whom, if anyone, the blame should fall; the number and nature of the casualties; and the disasters impact on the nations psyche. Utilising diverse sources, it evaluates Kempenfelts life and career, showing how gifted he was, uncovering his family tie to another famous Georgian admiral, and setting his flagships loss in its national context.

Kempenfelt was a man whose pen was as mighty as his sword, The Times (29 August 1913) observed in an editorial devoted to this remarkable sailor-scholar. As a thinker and naval reformer he had few equals and no superior among the great naval heroes of his time. Regrettably, however, William Cowpers dirge on the loss of the Royal George enshrines all that is now known to most of us about [him]. Long since generally accepted as an accurate account of Kempenfelts final moments, Cowpers famous scenario of the admiral trapped in his cabin, pen in hand, reflected a newspaper report of 31 August 1782. But as the present work shows, it was not the only contemporary version of Kempenfelts whereabouts. Had Cowper read a different newspaper, a rival scenario might have been immortalised and taken as gospel.

I owe much gratitude to Julian Mannering of Seaforth Publishing, and thank my editor Paul Middleton. I happily acknowledge the staff of various institutions for their kind and helpful responses to queries: Simon Bird, Curator, Ministry of Defence Art Collection, and his colleague Kelly Williams; Anne Delaney, Portsmouth History Centre; Jon Earle, Caird Library, National Maritime Museum; Heather Johnson, Archives Collections Officer, National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth; Alison Metcalfe, Curator of Missionary & Military Collections, Archives and Manuscript Collections, National Library of Scotland; Christine Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of Muniments, The Library, Westminster Abbey; Faye Rolland, National Records of Scotland; Carol Smith, State Library of Western Australia; Dr Melanie Vandenbrouck, Curator of Art, National Maritime Museum.

Sincere thanks also to Professor Timothy Wilson, together with Evelyn Lee and Margaret Woodcock, to naval and military records investigators RW (Bob) OHara and Susan Leggett for information from the National Archives, Kew, and to G Ian Goodson, Dr Michael A Jolles, Antoine Vanner, the late Peter Carlton Jones, and, last but certainly not least, my chief inspiration, my husband Bill.

One

THE ROYAL GEORGE AND ADMIRAL KEMPENFELT

Late August 1782. Britain was in the seventh year and fifth month of war with its rebellious American colonies. The Tory Lord North, following a vote of no confidence in his government over the loss of Yorktown the previous year, had resigned as prime minister in March. His replacement Lord Rockingham, a Whig, had died in July, and now another Whig, Lord Shelburne, held the post. Norths fall had meant a change of first lord of the Admiralty, with Admiral Augustus Keppel succeeding John Montagu, fourth Earl of Sandwich in that role. The Comte de Grasse, defeated by Admiral Sir George Rodney at the battle of the Saintes in April, had just been brought a prisoner of war to England, the first commander-in-chief of a French force so held on British soil since the reign of Queen Anne. On parts of the southern English landscape drenching rains had left their compensatory effect. [T]he country never was in such beauty; the herbage and leafage are luxurious, wrote art collector and man of letters Horace Walpole, son of Britains first prime minister, Robert Walpole, Earl of Orford, from his little Gothic castle at Twickenham near London. The Thames gives itself Rhne airs, and almost foams.

Meanwhile, all was hustle and bustle at Portsmouth, Britains premier naval port, where de Grasse had landed on the first of the month and, reaping the courtesy due to an honourable enemy, had been entertained to a most sumptuous dinner at the George Inn days later paid for by Vice-Admiral Sir Peter Parker, aboard whose ship he had arrived. At Spithead, the capacious sheltered roadstead between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, the Channel Fleet (also known as the Western Squadron, and colloquially as the Grand Fleet) had gathered, under the overall command of Admiral Lord Howe. It was making final preparations for sailing to the relief of Gibraltar, besieged from 1779 by France and Spain. Blockaded by a FrancoSpanish fleet and threatened by a huge land army, its British garrison, commanded by General George Elliot, was running out of food and supplies. Twice since the siege began British fleets had managed to enter the Bay with stores in January 1780 under Admiral Rodney and in April 1781 under Vice-Admiral George Darby. But, although the garrisons morale remained high, conditions had deteriorated again following Spains seizure of Minorca in July 1781, which put a stop to Minorca-based privateers under British colours running the Gibraltar blockade to the garrisons benefit.