Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Robert Bluford Jr.

All rights reserved

Front cover: Federal general Winfield Scott Hancock with division commanders (left to right) Francis Channing Barlow, David Bell Birney and John Gibbon. Petersburg, Virginia. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.729.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bluford, Robert.

The Battle of Totopotomoy Creek : Polegreen Church and the prelude to Cold Harbor / Robert Bluford Jr.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-251-5

1. Totopotomoy Creek, Battle of, Va., 1864. I. Title.

E476.52.B55 2014

975.5462--dc23

2014012330

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my profound appreciation to Dr. Edwin C. Bearss for his contributions to the manuscript on which this book is based. He kindly spent hours of his time and energy reading the textnot once, but twicefor accuracy and commented on my work. Dr. Bearss has few, if any, peers in his knowledge of the Civil War and is a world-known lecturer on the topic. He bears the title of chief historian emeritus of the National Park Service.

To my granddaughter Michelle, who transitioned this project from years of handwritten and manually typed notes into modern technology, goes a heartfelt thank-you for breathing life into this book.

Chapter 1

Polegreen Church

Polegreen Church was not just another old church. There are many old churches in the South, and a lot of them have bloodstained floors from being used as hospitals by both the Federals and Confederates during the Civil War. Polegreen was a special church and had been for more than a century before the war. It was special because it was the center of energy in the struggle for civil and religious liberty in colonial Virginia and because it was the church of Samuel Davies, the great dissenter and a minister of the gospel who gave more credibility to the Great Awakening in eighteenth-century Virginia than any other leader. He had no peer in terms of religious influence in colonial Virginia or perhaps even in colonial America.

Virginias General Assembly was the first legislative body in the world to adopt a statute guaranteeing religious freedom to all its citizens. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were the framers of the U.S. Bill of Rights, which was adopted in 1791, the first article of which was the same guarantee already granted to Virginians. These two political giants, Jefferson and Madison, have rightfully been given credit for their contribution to our Constitution and to our heritage. What is generally unknown, or unrecognized, is the half century of struggle for these freedoms that preceded the ratification of the Constitution. In particular, little is currently known of the enormous contribution to the struggle for these freedoms that was made by Samuel Davies. At the present time, considerable effort is being made to establish an appropriate memorial to Davies on the site where he began his exceptional work and founded Polegreen Church in 1748. This site has been registered as a historic landmark by the Department of Historic Resources of the commonwealth of Virginia and has also been placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the Department of the Interior. Without Samuel Davies, Polegreen may never have become a church and certainly would not have gained the renown it had in the middle of the 1700s. What immediately follows is a brief sketch of Davies and Polegreen.

Samuel Davies was born in 1723 in St. Georges, Delaware, the only son of Welsh parents. His mother, a devout Christian, had great difficulty in conceiving and, at his birth, named him after the biblical Samuel, meaning Gods gift. He was never a robust child. When, in his early teens, he sensed he was being called by God to be a minister, he went to a log college operated by Samuel Blair in Faggs Manor, Pennsylvania. This was in the day when formal education at a higher level was a rarity. Davies proved to be a diligent and brilliant student, though at the price of his health. When he finished his formal education at twenty-three years of age, he had tuberculosis.

It is essential to have an understanding of at least some dimensions of the situation into which Samuel Davies and the Presbyterian dissenters of Hanover County injected themselves. Certain social dynamics of the first half of the eighteenth century form the backdrop against which the struggle for religious freedom took place: the spiritual poverty of the church presided over by the Anglican priesthood, the beginning of the Great Awakening, the plight of the imported slaves and their descendants, the condition of the white indentured servants brought into the colony in large numbers, the strict control of religious expression (particularly in the Tidewater region) and the dwindling credibility of the Anglican priests themselves. This list could go on and on, but there are enough ingredients here noted to say that the situation in general was ripe for something explosive. Stated simply, the ties between the colonial government and its official religious institution, the Anglican Church, were about to unravel.

In 1983, the Pulitzer Prize for History was awarded to Rhyss Isaac for his volume The Transformation of Virginia, 17401790. This Australian, after ten years of research on eighteenth-century Virginia history, made some fascinating observations about the role of religion in contributing to the mood and substance of the American Revolution. A few sentences help illuminate those times:

Social disquiet was arising in Virginia by mid-century from a variety of causes, but the most dramatic signs of change appeared in the sphere of religion. A movement of dissent from the Church of England itself was commencing in the 1740s [sic]. In some places, common people were departing from the established churches into congregations of their own making. The parish community at the base of the barely consolidated traditional order was beginning to fracture. The rise of dissent represented a serious threat to the system of authority. The nature and extent of the anxiety produced in Virginia by the Great Awakeningthat astonishing revival that reached every region of colonial Americamust be examined before we can understand the sudden intensification of anticlericalism.

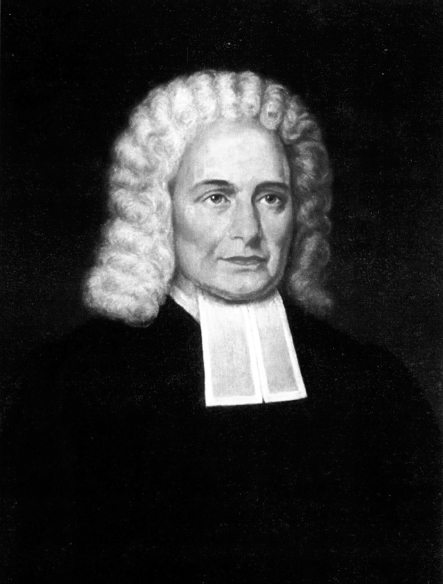

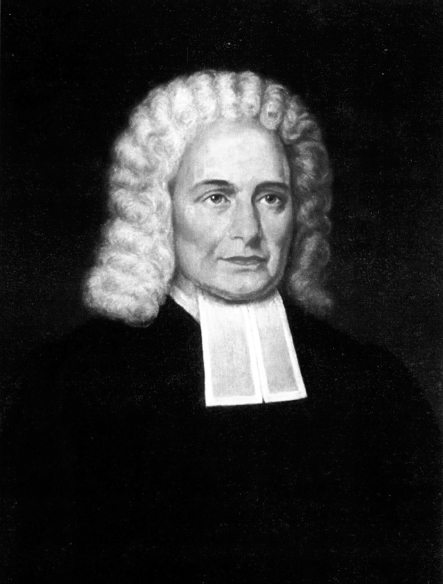

Samuel Davies, Presbyterian educator. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The first signs of the coming disturbance in traditionally Anglican parts of Virginia appeared in Hanover County in about 1743, when numbers of ordinary people led by Samuel Morris, a Bricklayer, began readings from George Whitefields sermons

Next page