While I was fortunate to spend time with the people mentioned below who shared many of their stories and family histories with me during our long interviews, I owe considerable thanks to the many rich and colorful characters quietly living in the Appalachian Mountains who are not mentioned, but whose hospitality and talent for storytelling allowed me understand the remarkable history of the Scots-Irish in America.

I owe a special thanks to two great research assistants, Rachel Hildebrandt and Michael Birmingham, for their hard work and resourcefulness, to Brandon Reed for his seemingly limitless knowledge of Southern racing history, to Colm Maguire for use of his eminently quotable brain, to Kurt Przybilla for his feedback throughout, and to Susanna Murphy who pitched in when the reading list kept growing.

To my agent Ryan Fischer-Harbage and to Nicole Robson for their faith in the book, to Laura Swerdloff at Sterling for her advice and great editing, and to my mentor Sue Shapiro, whose indefatigable energy started it all.

To my parents and my brother for their inexhaustible encouragement from the beginning, and to Adrian and Tommy who passed on to new adventures before the end.

INVASION OF THE

OTHER IRISH

N o sooner had the brigantine Friends Goodwill left the port of Larne in northern Ireland for Boston in 1717, than she sailed into winds shrieking out of the north. Gray clouds covered the sky and turned the ocean to blackness. Hundreds of passengers heaved as the ship rocked and waves crashed onto the deck. A low rumble of thunder was followed by a tremendous flash of lightning. The wind tore at the topsails; the mainsails ripped apart even as the sailors scrambled to lower them. A deluge fell from the sky. All hands grabbed buckets and spent five hours frantically bailing the ship out.

Chests, barrels, boxes, trunks, kettles, pots, pans and in fact every moveable article were tossed about in all directions, one migrant wrote of his voyage. This and the darkness that prevailed caused such a scene... men women and children call for relief and cry most earnestly for God to send them help.... Not a single passenger on board but conceived they had only a few minutes to spend this side of eternity.

Another wind change and the ship was bombarded by waves that rose to half-mast. This majestic ship that set sail with a sense of adventure and big hopes for a new life, was left destitute, her passengers and crew exhausted, vulnerable, and limping across the ocean.

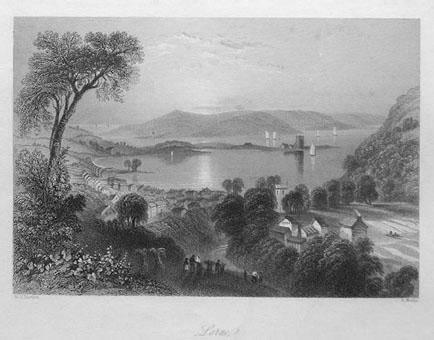

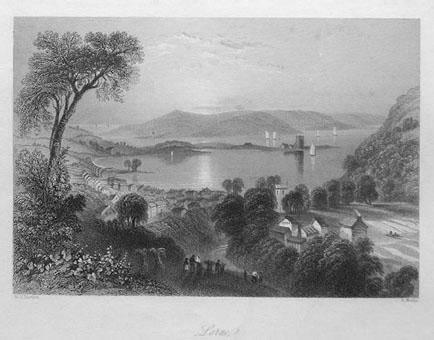

Only a few weeks earlier, five ships had readied to sail from Irelands northern harbors. It had been an exciting week of preparation for hundreds of families who packed up and took their leave of what was said to be one of the loveliest districts in Ireland. Their tiny hamlet was gently lapped by the silvery waves along the Atlantic shoreline. Little whitewashed cottages dotted the rolling mountains. Inside there was only a simple bed, a few iron pots, a basket of potatoes, and some peat for the fire that cooked their food and kept them warm through harsh winters. Smoke curls from the gable-end chimneys drifted away as the little party trekked along the soft forest pathway and gentle slopes on their long journey to the port of Larne.

A few miles south in Belfast Harbour, hundreds were heading for the brigantine Robert behind the Reverend James McGregor who led his flock from their little parish in County Derry. They owed him eighty pounds at the time he embarked in 1717, but he gave up the idea of getting it back and looked instead to a grand, new life in Massachusetts. Besides, America offered a much needed fresh start for McGregor. He had been admonished by the Synod of Ulster for drinking too much. But since he willingly admitted that less might have servd, his flock tolerated his failing by virtue of his honesty.

They passed the five-hundred-year-old Carrickfergus Castle that had protected the northern coast of Ireland from barbarian attack and the Houston and Jackson cottages that stood in its shadow.

Belfast Harbour was packed with people and their possessions when the Derry pioneers arrived. There was barely enough room to squeeze onto the pier for people who were singing, preaching, yelling, laughing, and clattering from all directions. Sailors added to the chaos, shouting orders as they scampered up rope ladders, hoisted the sails, loaded the decks, and made ready to depart.

Children in their Sunday best chased each other around the wagons and pallets. Street merchants sold their wares to whomever might have a shilling to spare. Friends and families cried and hugged and waved goodbye for the last time. There was never such a majestic sight as two brigantines docked in the harbor, wooden decks creaking, their massive sails unfurling, ready to catch the brisk Irish wind that would drive them across the ocean. Adventurers clambered aboard. Robust farmers, tradesmen, weavers, hardy women, and lively children dragged their supplies up the gangway and climbed below deck into steerage, where they were packed in like rats. McGregor stood on a mount to address his flock.

If thy presence go not with me, carry us not up hence, he quoted from Exodus.

We must say farewell to friends, relations, and our native land so that we may withdraw from the communion of idolaters and have the opportunity of worshipping God according to the dictates of conscience and the rules of his inspired word.

Port of Larne.

The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland, by J. Stirling Coyne, illustrated by W.H. Bartlett (London: George Virtue, ca. 1840). Image provided by Kitty Liebreich, www.kittyprint.com.

A bargain was made between the captain and those passengers who couldnt afford the fare: the migrant agreed to be auctioned off as an unpaid, indentured servant when they landed. The captain got his cut of the sale, and after about four years in the service of some wealthy American, the migrant would be sent on their way with a cow, a coin, and maybe a piece of land. It seemed as good a way as any to get to the New World.

Transporting indentured servants was a lucrative business that attracted a new menace to the pier. Rural youths who dreamt of sailing away on a galleon one day were lured aboard for a tour of the ship, then knocked out or drugged, remaining unconscious until they were long out of port, and would later find themselves up for sale on the other side of the Atlantic.

For those who retired to the local tavern to wet their whistles, there was another culprit at largethe British navy. Many men gulped down a mug of ale only to catch sight of a shilling at the bottom. It was an old British navy trick that legally bound the customer to the navy on the grounds that he had accepted the Kings shilling. Without a chance to take their leave of family or friends, they were off to a stinking, poorly ventilated, overcrowded, bug-infested ship, upon which no sane man would volunteer to serve.

In both harbors sailors cast off the lines and weighed anchor. The Irish wind set them off on their grand adventure into the wild unknown, where they believed their character, resilience, and fortitude, forged from decades in the wild countryside, would keep them in good stead.

In Larne the Friends Goodwill sailed with Captain Goodwin at the helm. In Belfast the Robert set sail under Captain Ferguson, with McGregor, his flock, and a family of Armstrongs on board. John Armstrong was a respectable local tradesman, but he had little money and hadnt secured employment in advance. He would need to convince a court in Boston that he and his family were self-sustaining.

Next page