Slavery Today

Kevin Bales & Becky Cornell

The Betrayal of Africa

Gerald Caplan

Sex for Guys

Manne Forssberg

Technology

Wayne Grady

Hip Hop World

Dalton Higgins

Democracy

James Laxer

Empire

James Laxer

Oil

James Laxer

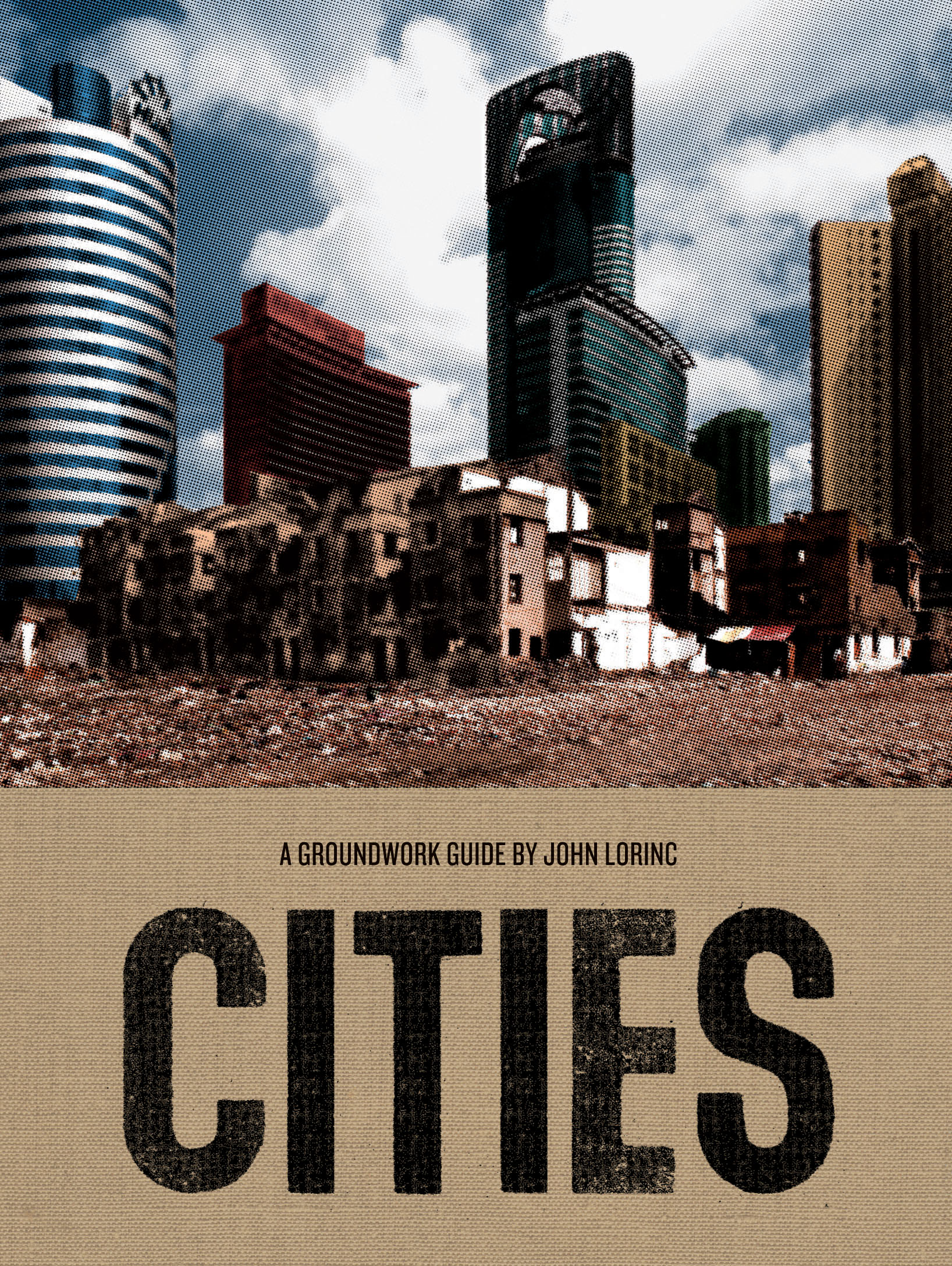

Cities

John Lorinc

Pornography

Debbie Nathan

Being Muslim

Haroon Siddiqui

Genocide

Jane Springer

The News

Peter Steven

Gangs

Richard Swift

Climate Change

Shelley Tanaka

The Force of Law

Mariana Valverde

Series Editor

Jane Springer

Cities John Lorinc | Groundwood Books House of Anansi Press | Toronto Berkeley |

Copyright 2008 by John Lorinc

Published in Canada and the USA in 2008 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press

128 Sterling Road, Lower Level, Toronto, Ontario M6R 2B7

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

We acknowledge for their nancial support of our publishing

program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) and the Ontario Arts Council.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Lorinc, John

Cities : a Groundwork guide / John Lorinc.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-88899-820-0 (bound).

ISBN-10: 0-88899-820-1 (bound).

ISBN-13: 978-0-88899-819-4 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-88899-819-8 (pbk.)

1. Cities and towns. 2. Rural-urban migration. 3. Urbanization.

I. Title.

HT151.L675 2008 307.76 C2007-9005214-X

Design by Michael Solomon

Contents

For my mother, Eva, and my sister, Julie

Chapter 1

The Urban Century

The year 2008 marked a watershed moment in the evolution of human society. For the rst time in history, more than half of the worlds 6.6 billion inhabitants were living in cities rather than rural areas. In the industrialized world, the population has become steadily more urbanized since the mid-nineteenth century, when the Industrial Revolution transformed villages and market towns into manufacturing and commercial centers. By the late twentieth century, however, many countries in the developing world especially in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East were experiencing extremely rapid urbanization as millions of people were leaving, or eeing, the countryside to nd jobs and a new life in big cities.

Theres no reason to expect this trend to slow or reverse itself, so the health of cities is a topic of enormous signicance. After all, if most of us live in cities, we need to understand how these complex places function socially, economically, culturally, spiritually, environmentally and politically. We must be conscious of how cities throughout history prospered or fell into decline, why some became dynamic hubs of cultural or scientic innovation while others allowed tyrants to build brutal regimes. In an age of mass migration and global trade, we should also be aware of the experiences of cities like New York, Hong Kong, Toronto places that have been rapidly reshaped by international commerce and immigrants with new cultural tastes, architectural practices and commercial connections.

Yet as much as we need to be aware of the many strands of urban history, the extraordinary challenges facing twenty-rst-century cities have no precedent. The past offers few lessons on how megacities with tens of millions of residents many of them desperately poor should manage growth, deliver services or govern themselves. In some of the richest Western cities, such as Los Angeles and London, staggering wealth co-exists with grinding poverty. In cities like So Paulo and Istanbul, dense shanty towns have sprung up on hillsides and marginal land. Globalization has created explosive economic growth in urban China while sapping the vitality of once-prosperous cities in the US rust belt. Around the world, urban population growth and consumerism are contributing to extreme forms of environmental degradation: sprawl, pollution, global warming due to greenhouse gas emissions, water contamination, overconsumption of nonrenewable energy sources, mountains of waste.

No one disputes the seriousness of these problems. At the same time, there is room for optimism. Throughout history, urban centers have often proven to be not only highly adaptable, but engines of civilization and oases of tolerance. Cities have been described as the greatest of all human creations. Their task, in this century, will be nothing less than saving humanity from its worst excesses.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, city derives from a twelfth-century Middle English word coined to describe human settlements that were larger and more important than towns. These were religious centers, commercial capitals or walled cities built for strategic purposes.

The emergence of a word is always an important signpost. It acknowledges a societys need to name something new. There had been great cities long before the twelfth century, of course ancient Babylon, Athens, Alexandria, Imperial Rome, Kyoto. But after the collapse of the Roman Empire, many European and Middle Eastern cities fell into a long period of decline that lasted until the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when urban centers began to re-assert their importance.

What, then, is a city if not just a large town? This question raises others: how far does a citys inuence extend? Who should govern its residents? What are the rights and obligations of those who live in and near cities? And how do local politics shape urban areas?

Begin with the problem of boundaries. Medieval cities often surrounded themselves with formidable walls to keep out invaders. But these cities expanded as traders and refugees settled outside the walls. Other cities, such as London, emerged as clusters of towns blending into one another, creating highly integrated urban areas with diverse economies that attracted newcomers from surrounding rural regions.

To this day, big cities grow relentlessly, expanding into the hinterland beyond their fringes. In the West, this phenomenon is known as sprawl the outward push of subdivisions, shopping malls, highways and industrial parks. In the developing world, meanwhile, many major cities are ringed by vast slums (a.k.a. squatter communities or shanty towns, or in Brazil, favelas ) that grow on steep slopes or derelict government land.

Such development patterns always create tensions in the relationships between the urban core and its periphery. Economically, the inuence of cities tends to radiate outward, even though wealth ows into urban regions. In North America, major metropolitan areas are surrounded by exurbs quiet towns that may appear to have a rural character, but whose residents commute to the city or depend on its presence in other ways. In commercial hubs like Tokyo or Frankfurt, the urban inuence extends even further: those who work in the nancial districts of such cities routinely make investment decisions with global implications.

Next page