Slavery Today

Kevin Bales & Becky Cornell

The Betrayal of Africa

Gerald Caplan

Sex for Guys

Manne Forssberg

Democracy

James Laxer

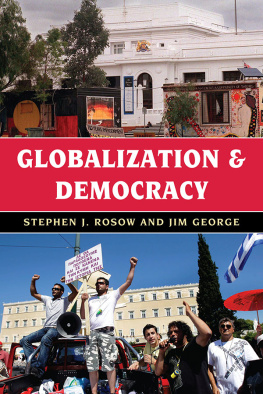

Empire

James Laxer

Oil

James Laxer

Cities

John Lorinc

Pornography

Debbie Nathan

Being Muslim

Haroon Siddiqui

Series Editor

Jane Springer

Genocide

Jane Springer

Climate Change

Shelley Tanaka

Democracy James Laxer | Groundwood Books House of Anansi Press | Toronto Berkeley |

Copyright 2009 by James Laxer

Published in Canada and the USA in 2009 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press

128 Sterling Road, Lower Level, Toronto, Ontario M6R 2B7

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

We acknowledge for their nancial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) and the Ontario Arts Council.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Laxer, James

Democracy / James Laxer.

(A Groundwork guide)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-88899-912-2 (bound).ISBN 978-0-88899-913-9 (pbk.)

1. Democracy. 2. Globalization. 3. Economic policy.

4. Sustainable development. I. Title. II. Series: Groundwork guides

JC423.L39 2009 321.8 C2008-905685-X

Contents

To Michael, Kate, Emily and Jonathan

Chapter 1

What Is Democracy?

In the West, citizens assume that they live in a democracy. By this they mean that they have the right to vote in elections to choose the people who will hold positions of power in the various levels of government in their country. They feel that they can express themselves freely on the issues of the day, holding whatever opinions they wish on the political leadership of their country without fearing negative reprisals for disagreeing with those in power.

When they think about democracy, it is natural for people to contrast it with dictatorship a system of government in which one party or political leadership holds power, there are no fair elections among various political parties, and expressing negative views about the party in power or the leaders of the country could lead to a knock on the door from the police, to imprisonment, and in extreme cases to assassination or execution.

The word democracy is derived from the Greek and it means rule by the people. The ancient Greeks who developed the concept of democracy had no problem with the existence of slavery within a democracy with the idea that citizens should have full rights while slaves could be treated like beasts of burden. In the city-state of Athens in the fth century BC, for instance, citizens were expected to participate in the affairs of government and to take a direct role in the decision-making process. Only adult males over eighteen years of age had the right to participate. Slaves and women, as well as non-citizens who had a right to live in Athens, were barred from such participation. Involvement in Athenian democracy, therefore, extended only to a minority of the population, perhaps 20 percent of adults.

Democracy in modern nation-states almost always takes the form of representative democracy. That is to say, the citizens elect ofceholders at various levels of government (municipal, state or provincial, federal or national), and those elected serve as the representatives of the people.

In ancient Athens, the system was one of direct democracy. Under such a system, all of the citizens gathered in a forum a number of times a year to make decisions. In Athens, the Assembly, attended by all citizens who were in the city and able to be present, met ten times a year and held additional meetings when necessary. The Assembly made major decisions regarding the granting of citizenship, the election of certain ofcials, and whether to go to war or to pass pieces of legislation. Speakers argued the case for and against particular propositions, and then the Assembly decided in a show-of-hands vote. Thousands of citizens took part in these meetings, and for certain types of decisions a quorum of six thousand citizens had to be in attendance.

Another key governing body in Athens was the Council of Five Hundred. The members of this body were selected by lottery each year from among the citizens who were thirty years of age or older. Citizens were allowed to serve on the Council twice in their lives. The Council prepared draft legislation for the Assembly, and in some instances it put the Assemblys legislation into effect.

The courts were also crucial to the Athenian system, and their jury panels were selected by lot from among citizens at least thirty years of age. Depending on the type of case involved, whether it was a public action brought against someone or a private suit, the number of jurors varied. There were no judges.

To the Athenian citizens of those times, the system of democracy that exists in nation-states today would seem highly undemocratic. They would be deeply suspicious of a system in which millions of citizens living in a large territory elect professional politicians from competing political parties to represent them. How can you trust such politicians? they would lament. And how can you entrust them with so much power for such long periods of time? To the practitioners of direct democracy (a system that could work in theory in a small city-state today, with all citizens having the right to participate), representative democracy appears to permit the citizen to do little more than vote every few years, while leaving the actual passing of legislation up to the professionals.

These criticisms have been voiced by many analysts in our own time and over the past two and a quarter centuries during which the modern democracies have developed. Jean Jacques Rousseau, writing in the eighteenth century, believed that a city the size of his native Geneva had the ideal population for a democracy. In such a setting, direct democracy, the kind he favored, could ourish.

In our own era, the participants in the anti-globalization movements that have sprung up in many countries over the past two decades regard the decision-making process in contemporary nation-states as highly bureaucratic and undemocratic. They believe that the major states have fallen under the effective rule of multinational corporations that pursue strategies resulting in the exploitation and impoverishment of much of the world. To these often young activists who appear at summits of the leaders of the top industrial nations (the G8) or meetings of the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank, a new world order is needed to eliminate poverty and exploitation, and a system of real democracy is required. Usually, the anti-globalization activists have in mind a much more localized, decentralized economic system that in addition to representative government would allow workers to have control over their workplaces.

Next page