This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1997 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

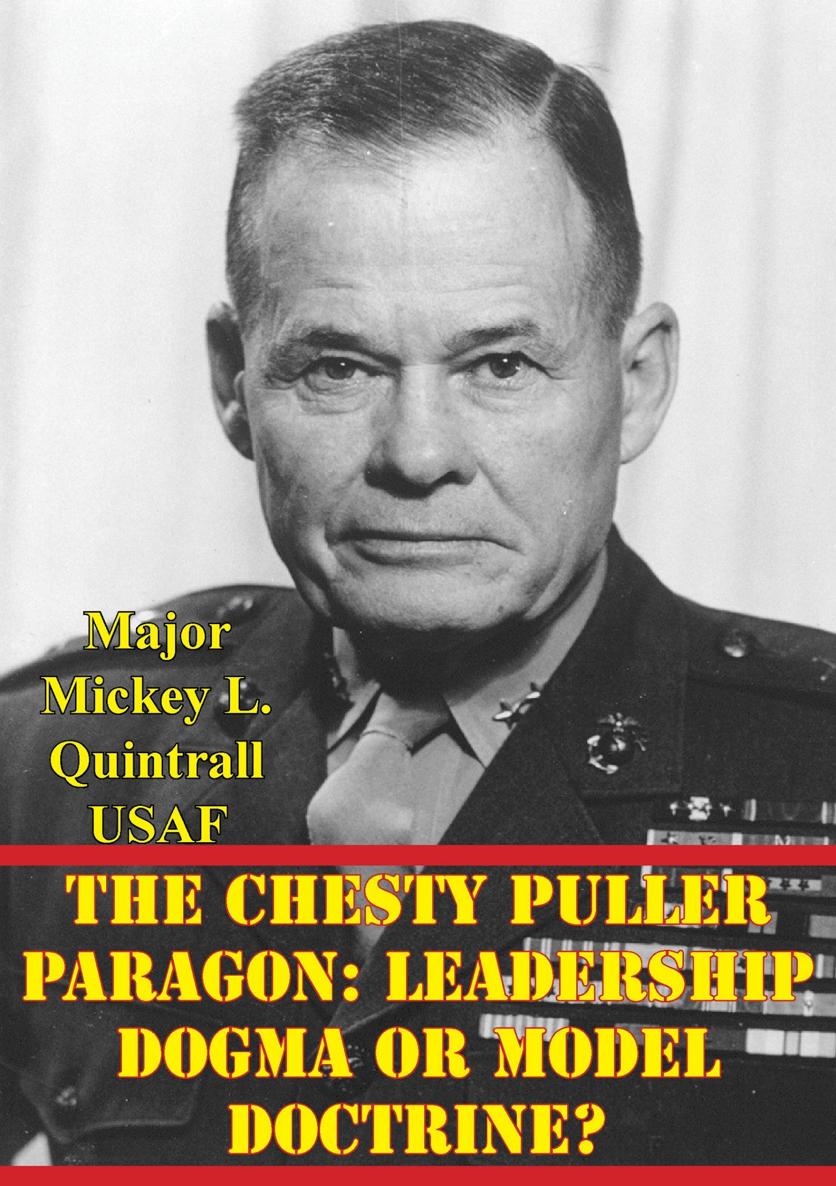

THE CHESTY PULLER PARAGON: LEADERSHIP DOGMA OR MODEL DOCTRINE

By

Mickey L. Quintrall, USAF

ABSTRACT

In this study, I examine whether or not the United States Marine Corps senior warrior-leaders should continue to use heroic-warriors from the 1942-52 era as contemporary paragons of tactical leadership. Additionally, I compare the Marine tactical leadership models between 1942-52, and their relevance within the cultivated and refocused leadership doctrine of todays Marine Corps. Then, I examine whether or not there is a gap created using an earlier eras tactical leadership example to model contemporary tactical battlefield leadership.

The Marine Corps tactical leadership criteria and what the Corps expected of its commanders during World War II and the Korean War is the starting point. There was not much written leadership guidance then, but there was accepted leadership doctrine, nonetheless. Today, several United States Marines are recognized as setting the contemporary paragon for the ideal tactical battlefield leader. Among them, is World War II and Korean War Marine Lewis Chesty Burwell Puller. Chesty Puller not only set a courageous combat example, he trained his men hard, respected his mens fearlessness, and worked hard to build unit comradeship.

Service parochialism and cultural turmoil through the Vietnam War set the stage for a rocky period in the history of the Corps, leading up to the Commandants re-focus on a new Marine followership-leadership ethos. The Marine Corps recent efforts to Transform their Marines into a new breed is an attempt to transform leadership dogma to leadership-followership doctrine. His fresh approach is thought to better inculcate the Marine culture with loyalty and commitment to the Corps, similar to what was experienced within World War II Marine Corps.

The thrust of the monograph pursues the question: Does Chesty Puller provide the right contemporary leadership example, or does he perpetuate dogma?

BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

When one door closes, another opens; but we often look so long and so regretfully upon the closed door that we do not see the ones which open for us. {1} Alexander Graham Bell

Referred to as The Invincible, by both his men and his enemies, Alexander the Great had what Carl von Clausewitz called the inward eye or coup dil . His courage on the battlefield, fighting and commanding along-side his men, fired their imagination and awoke in them the mystical faith that led them to accept, without question, that there was nothing he would not dare; nothing he could not do in the pursuit of victory. {2} The warrior-leadership he displayed worked for the battles during his era. Similarly, historians write that Caesar, Napoleon and other Great Captains led armies with personal versions of an inward eye. Their warrior-leadership was shown to produce superior armies that dominated the battlefields of their time. Time, however, has also proven that their elite warrior-leadership has not kept pace with the technological and doctrinal changes of the evolving battlefield.

The personality and the character of the tactical commander has always played a key role on the battlefield. Whereas emperors, kings, and commanders-in-chief once led men into battle, the warrior ethos and warrior-leadership continues to change. During the American Civil War generals continued to lead the tactical battle from the front, but the commander-in-chief led and managed the operational battle from the rear. Some say is was a lack of courage, history however suggests that their position, short of the kill line, better served the force. John Keegan, in his book, Mask of Command , weighed General Ulysses S. Grants battlefield leadership during the American Civil War. Keegans study determined that the General Grant often refused to lead by example onto the tactical battlefield and would rather command from behind musket range. {3} Nonetheless, history rightfully paints Grant as one the great military strategic and operational leaders. Grants Personal Memoirs certainly provide a clear discussion of war-time leadership amid chaos, confusion, and ravage of battle. Indeed, for the Civil War, Grants idea of tactical warrior-leadership made sense. The ilk of a tactical battlefield commander, however, continues to change with time.

Militaries have searched for the character of a warrior-leader for at least two thousand five-hundred years. Sun Tzu, Clausewitz, and Antoine Jomini are just a few of the men who defined what it takes to be a warrior-model. Today, US Army doctrine alludes to this warrior-spirit as the knack of forging victory out of the chaos of battle; to overcome fear, hunger, deprivation, and fatigue. {4} This is one services definition. However, do todays services adequately consider the increasing complexity of the battlefield in their leadership doctrine?

Leadership must adapt to the character of the battlefield to be effective. Likewise, the science or doctrine of combat leadership will require adaptation to meet contemporary and future battlefields. Frederick The Great and Napoleon Bonapartes defeats are just two examples of tactics and leadership styles that worked in their time, but not in the twentieth century.

This monograph intends to examine whether or not the United States Marine Corps senior warrior-leaders should continue to use heroic-warriors from the 1942-52 era as contemporary paragons of tactical leadership. Although Marine Corps tradition cannot brush aside their legends of warrior-leadership and stories of battlefield victories, when is it right to establish new contemporary leadership models. Moreover, what role should former heroic-leaders hold in the Marine Corps annuls?

The Marine Corps battlefield leadership of the forties and early fifties was different than what is required today of the Marines self-acclaimed 911 mission. The leadership doctrine and training of a tactical commander from both eras are similar in only the most axiomatic Marine traditions and customs. Training and fighting in each time period reveals drastic differences. Not only was written Marine Corps leadership doctrine prior to World War II fundamentally non-existent; {5} except for the basic training prospective Marines received in Officer Candidate School or Boot-camp, leadership skills were learned from senior Marines; handed down from Marine-to-Marine. It had been that way, to some extent, from the Corps beginning in 1775.