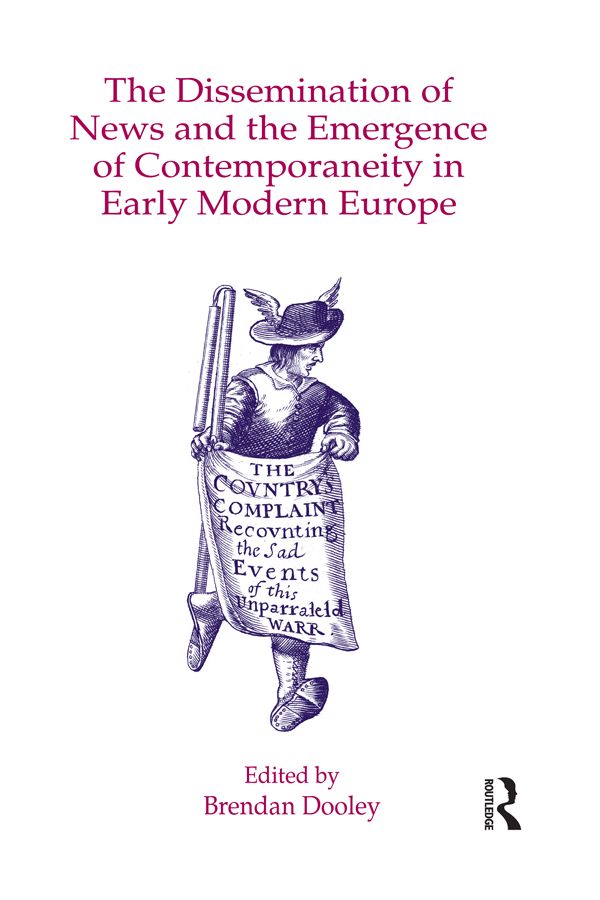

The Dissemination of News and the Emergence of Contemporaneity in Early Modern Europe

First published 2010 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Brendan Dooley and the contributors 2010

Brendan Dooley has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

The Dissemination of news and the emergence of contemporaneity in early modern Europe.

1. Communication, InternationalHistory16th century. 2. Communication, International

History17th century. 3. PressEuropeHistory16th century. 4. PressEuropeHistory

17th century. 5. CommunicationSocial aspectsEuropeHistory16th century.

6. CommunicationSocial aspectsEuropeHistory17th century.

I. Dooley, Brendan Maurice, 1953

302.209409031dc22

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The dissemination of news and the emergence of contemporaneity in early modern Europe

/ Brendan Dooley [editor].

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-7546-6466-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Newspaper publishing

EuropeHistory. 2. European newspapersHistory. 3. PressEuropeHistory. 4.

CommunicationEuropeHistory. I. Dooley, Brendan Maurice, 1953

PN5110.D57 2010

079.4dc22

2009040616

ISBN 9780754664666 (hbk)

Contents

13.7 Crouch Weighted Score for ModIntell171#2 as Candidate Derived Text, WPostWood171 as Candidate Source Text

(overall score: 0.188)

13.9 Weighted Score Output for ModIntell171 as Candidate Derived Text, WPost171 as Candidate Source Text

(overall Score: 0.364)

13.10 Weighted Score Output for ModIntell171 as Candidate Derived Text, WPostWood171 as Candidate Source Text

(overall score: 0.872)

Paul Arblaster currently teaches at the Facults Universitaires Notre-Dame de la Paix, Namur, Belgium.

Alessio Assonitis is the Research Director of the Medici Archive Project in Florence, Italy

Zsuzsa Barbarics-Hermanik teaches Early Modern and Southeast European History at University of Graz, Austria.

Astrid Blome is a researcher at the research institute Deutsche Presseforschung and teaches in Bremen University.

Cristina Borreguero Beltrn teaches Early Modern History at the University of Burgos, Spain.

Nicholas Brownlees teaches English Language and Linguistics in the University of Florence, Italy.

Charles-Henri Depezay received his doctorate from the University of Orleans, France.

Brendan Dooley teaches Renaissance Studies in the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences at University College Cork, Ireland.

Andrew Hardie teaches Linguistics at Lancaster University.

Mario Infelise teaches Modern History at the University of Venice.

Tony McEnery teaches English Language and Linguistics at Lancaster University.

Ingrid Maier teaches Russian Language and Literature at the Uppsala University, Sweden.

Scott Songlin Piao is a Researcher in the Computing Department at Lancaster University.

Sonja Schulthei-Heinz teaches Early Modern History at the University of Bayreuth.

Daniel Waugh teaches history in the University of Washington, Seattle.

Johannes Weber teaches Modern German Literature at the University of Bremen.

Brendan Dooley

What is contemporaneity? As understood by the authors of this book, it is the perception, shared by a number of human beings, of experiencing a particular event at more or less the same time. It is not simply a crowd phenomenon, since the observers in question may be out of sight or earshot of one another and still imagine themselves as a group. Depending on the scale of the event and the size of the group, it may have important consequences from a social, cultural and political standpoint. At the very least, it may add to a notion of participating in a shared present, of existing in a length of time called now. Distributed over a certain geographical space or spaces, it may contribute to individuals sense of community, or their identification with one another. With good reason, anthropologists and historians have identified it as a hallmark of modernity. Although it is as familiar to modern-day humans as the news in the media, we believe it has a historya history dating back to early modern times. That was when the first world-wide communications networks emerged; and in spite of the frequent delays, shiifting borders, linguistic barriers, unreliable carriers and differences in the reckoning of time, Europeans began to share a knowledge of one another and of events in the world taking place in the present. Already in the seventeenth century, something of what happened in Venice was known in Strassburg, events in Palermo were on the pages of papers in Augsburg. People could have a concept not only of living within a European social space, a European theater of political, social and economic reality, but of knowing what was going on in many parts of it contemporaneously. They also might begin to apprehend a differentiation within Europe, along East/West and perhaps North/South lines. The emergence of contemporaneity may have helped form the basis for the much more widespread and deeper sense of contemporaneity that was to emerge later on.

But how was contemporaneity experienced in the early modern period? How indeed was it distinguished from other perceptions of time and place? What were the stages in its development and diffusion? How can the historian trace it? The authors of these essays share the conviction that the answers are to be found largely within the history of news and news publications; and accordingly, they focus a diverse array of methods, in some cases developing new historiographical approaches, using a wide variety of sources, centered in a myriad of geographical locations.

Contemporaneity was made possible by uniting time and space. If uniting time and space was a challenge in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it may occasionally be so still today. And the effort of building a project based in England, Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Spain, Sweden and the USA has required the combined effort of many, including the contributors, who have all supplied far more than just their texts. In addition, we would like to thank Lara Fleischer, Anne Heyer, David Lucker, Catalin Moscaliuc, Barbara Marti Dooley and all the others who have made the text editing a lighter task. Uros Urosevic provided precious research assistance when time was particularly scarce; Mitul Jain supplied technical support. Thanks also to the Presseforschung unit of the University of Bremen, located within the Bremen Staats- und Universitaatsbibliothek, and especially Holger Bning, for support and hospitality. Finally, we would particularly like to thank Jacobs University in Bremen, supplier of a true locus amoenus for our collaborative endeavors on two occasions, in December 2006 and 2007, when our research group met to discuss many of the issues presented in this volume, and in between these times, when it hosted the invisible academy of our collective communications over two years.