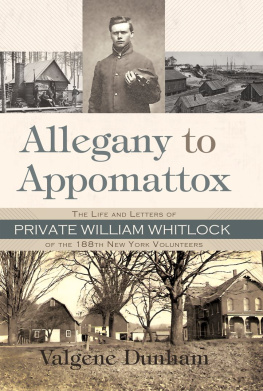

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2019 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Ingeborg

Printer and binder: Sheridan Books

The William J. Whatley Letters are reproduced here with the permission of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas, Austin.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8071-7069-4 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-7131-8 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-7132-5 (epub)

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

For Melba

I am sick and tired of trying to do a mans business when I am nothing more than a contemptible poor piece of multiplying human flesh tied to the house by a crying young one, looked upon as belonging to a race of inferior beings.

LIZZIE NEBLETT , Texas housewife and letter writer, Anderson, Texas, 1862

Let me tell you what is coming. After the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives you may win Southern independence, but I doubt it. The North is determined to preserve this Union. They are not a fiery, impulsive people as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche.

SAM HOUSTON , Galveston speech, April 19, 1861

FOREWORD

The wartime correspondence between William Jefferson Whatley and Nancy Falkaday Whatley, husband and wife, spans only half the year of 1862. Yet here in these letters, written between May 23 and December 31, are found in compressed form many of the grand, sweeping themes that marked the Civil War, which lasted for four long, bloody years. In just a seven-month period, the Whatleys suffered the devastating effects of the war, on the home front and in Confederate military encampments. Their initial optimismthat the war would be short, that they could keep intact their small plantationgradually gave way to despair. Their letters chronicle the dislocations caused by troop mobilization and the grinding, everyday slog of a conflagration that would seem to go on forever among those engulfed by it.

The Whatleys correspondence tells the moving story of a young couple and their four children, with Nancy (age twenty-five) remaining at home in the vicinity of Caledonia, Rusk County, Texas, and William (age thirty-one) deployed to Arkansas. The couple were separated by a relatively short distanceNancy, in northeast Texas near the Louisiana line, was about three hundred miles from William when he was stationed at Camp Nelson in central Arkansas. Nevertheless, to them the distance felt vast, and they relied on writing and receiving letters to maintain contact with each other. When William left for the front, Nancy assumed charge of the small plantation, which depended on thirteen enslaved workers to tend cows, chickens, pigs, horses, and a mule; grow corn, peas, potatoes, turnips, and cotton; and produce cotton cloth. The Whatleys letters to each other reveal the difficulties she faced overseeing enslaved workers, and the deprivations and frustrations he endured on the march and in camp. Their affection for each other and for their children is palpable, their attention to the details of everyday life illuminating.

At the same time, as a historical source and a particular literary genre, the letters pose three main challenges for the reader. The first concerns the motivation of the correspondents themselves. Did husband and wife each try to minimize the hardships they faced in order to put the others mind at ease? For example, William boasts that he is enjoying robust health and is gaining weight in camp: Can the reader accept his claims at face value? Or is he consciously trying to reassure his anxious, harried wife? In any case, both seem to be keeping up a brave front for the other, suggesting we need to be cautious in assessing their state of mind as well as their material circumstances while writing the letters.

The second concerns the behavior of William and Nancys neighbor, Mr. Martin, who has agreed to help Nancy manage the day-to-day operations in her husbands absence. Both William and Nancy express keen disappointment, if not anger, when Martin does not live up to their expectations. Seen from the Whatleys perspective, Martin appears irresponsible and unfeeling, as the young wife makes seemingly heroic efforts to keep the place and her family together in Williams absence. Yet it is possible that Martin had his own household to worry aboutperhaps ill children, sons away at war and wounded or even recently killed, or obligations imposed upon him by extended kin. We know that he proves to be an unreliable friend to the Whatleys, but we do not know the reasons for his inconstancy. Nancy seems resentful when he complains that her hogs have trampled his cornfield, but perhaps his trials were just as heavy asor heavier thanhers. Did he callously betray the couple, or did he do his best under harrowing conditions?

Finally, we must glean from Nancys writingsan inadequate source to be sure, but the only one availablehints about the struggles of the Whatleys enslaved workers during these months in 1862. The six adults and six or seven children too endured the wrenching effects of war. We get glimpses of the liberties they took, the opportunities they seized, once William was away from home and Nancy found herself consumed by her roles as housekeeper, mother, and plantation manager. After the cotton crop was laid by (i.e., planted) in early June, these workers seemed impervious to her entreaties to toil hard at other tasks around the place. They shirked work and gave a neighboring white man some saucy jaw. When they claimed to be unwell and unable to labor in the fields, were they feigning illness or not? That they remained on the property suggests they made a shrewd calculationthat as individuals and family members they would be better off in a familiar place, one that provided them with sufficient food and shelter. If they fled and took their chances on the open road, they would be vulnerable to bushwhackers, Confederate soldiers, and citizen patrols. It is therefore incumbent on the reader to keep in mind that the Whatleys aim to keep the small plantation functioning according to prewar routines was not the aim of their enslaved workers, who began to test the limits of bondage as soon as William left home.

William spoke for many of his comrades-in-arms early in the war when he proclaimed that he was battling for Nancy against advancing Union forces. He could at times fall back on his own bravado to reassure his wife that he would protect his family, telling her that we are a perfect terror to the feds, and assuring the children he would return home soon, but only after he kill[ed] all the Yankees. William believed that white Southerners should forge their own nation; at the same time, he exhibited a great deal of pride as a Texan. In May of 1862 he could hardly foresee the ways that his commitment to military service would lead to the disruptionand in some respects the destructionof the ideas and people he held dear.