ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS:

THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

Volume 33

RECOLLECTIONS OF A

LABOUR PIONEER

RECOLLECTIONS OF A

LABOUR PIONEER

FRANCIS WILLIAM SOUTTER

First published in 1923 by T. F. Unwin

Republished in 1984 by Garland Publishing, Inc.

This edition first published in 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1923 Francis William Soutter

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any Form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-32435-0 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-43443-3 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-32885-3 (Volume 33) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-44838-6 (Volume 33) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Recollections of

a Labour Pioneer

Francis William Soutter

Garland Publishing, Inc.

New York & London

1984

CONTENTS

For a complete list of the titles in this series see the final pages of this volume.

This facsimile has been made from a copy in the Yale University Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Soutter, Francis William.

Recollections of a labour pioneer.

(The World of labour: English workers, 18501890)

Reprint. Originally published: London: T. F. Unwin, 1923.

1. Soutter, Francis William. 2. Labor and laboring classesGreat BritainBiography. 3. Labor and laboring classesGreat BritainPolitical activityHistory19th century. I. Title. II. Series: World of labour. HD8393,S6A3 1984 322.20924 [B] 83-48499

ISBN 0-8240-5726-0 (alk. paper)

The volumes in this series are printed on acid-free, 250-year-life paper.

Printed in the United States of America

RECOLLECTIONS OF

A LABOUR PIONEER

P O L I T I C A L

E N G L A N D

A CHRONICLE OF THE 19TH CENTURY TOLD TO MISS MARGOT TENNANT BY SIR ALGERNON WEST. 7s. 6d. net.

T. F ISHER U NWIN , L ONDON

RECOLLECTIONS OF

A LABOUR PIONEER

By FRANCIS WILLIAM SOUTTER

I NTRODUCTION BY T. P. OCONNOR, M.P.

T. F I S H E R U N W I N L T D

LONDON : ADELPHI TERRACE

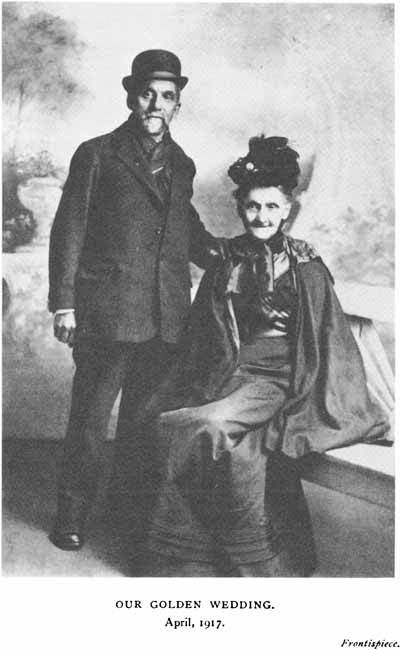

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY DEVOTED WIFE

ARABELLA AMELIA CAMPBELL SOUTTER

I DEDICATE THIS VOLUME

Who for fifty years and eight months shared with me the joys and sorrows of life. Ever true to the history of her Clan, she knew not fear, was unswervingly loyal to high principles and lofty aims, and by her heroic example became the inspiration of my life.

First published in England 1923

(All rights reserved)

W HEN I came to London first in the year 1870, I was not only young and untravelled but singularly ignorant; and I was most ignorant, curiously enough, about England and Englishmen. I belonged to a race that is even more insular than the Englishthough they are insular enough; and one of the first things I had to get rid of was this insularity. I had no racial resentmentthat I have never had at any time of my lifebut I had a good deal of racial misunderstanding. I remember still my ardent disputes with an Englishmana fellow-journaliston the question whether the English or the Irish were the more sentimental race; and I drew a portrait of the Englishman as I pictured him at that timeI had not left Irelandand the portrait was of a man very wonderful in business, usually very rich, very self-indulgent, very calculating; above all, free from sentiment. Especially did I exclude from his emotions and habits the sentiment of love, and marriage for love; and when my English comrade told me that most marriages in England were made without a dowryor, as we call it in Ireland, a fortune, either asked or givenI just listened with the idea that he was, so to speak, pulling my leg, with bold inventiveness not foreign to his nature.

I soon found, unexpectedly, in unexpected places, Englishmen who either confirmed or removed my ignorance. A priest who gave me an excellent supper of hot roast beef and creamy boiled potatoes confirmed my ignorance. I had never eaten a supper in my life, and a supper of hot beef and creamy potatoes, and at the table of a priestit was an outrage on my ascetic creed. But soon after I was taken to see a gentleman who, I was told, had written seventy pantomimes. You know what the position to-day would be of a man who had written seventy pantomimes: he would probably live in a luxurious flat, drive in a motor car, and dine at the Savoy or the Carlton. But my poor acquaintance lived in a single room in a Westminster slum. There was a pallet and just one chair; and as I made to sit on the chair, the bald-headed, genial, sweet old manfor such he certainly wasseemed alarmed, and begged me not to do so. On the chair, he explained a moment afterwards, was his suppathus he pronounced it, in the then to me unfamiliar Cockney accent. And as I looked on this poor, poverty-stricken, tired, simple old gentleman, seated on that miserable little bed in a room without furniture, with all this record of hard work behind him, I had one of those moments of pity and vision that accompany what Nonconformists call conversion.

That England of universal wealth, that Englishman of arrogant frigidity, were blotted out of my mind for ever. I was very poor, very anxious myselfI hadnt yet got a joband I knew that this poor old writer of pantomimes and myself bridged all the abyss I had supposed between the Englishman and the Irishman. Everywhereamid all countries, among all racesthe mass of men were the same, striving hard, and usually unsuccessfully, for the simple bed and the modest board that kept body and soul together. This was the beginning of that understanding and affection for the English people which I have entertained ever since, and which have grown with my years.

It was in that little room in a Westminster slum, also, that I became what I have ever since remainedan international democrat, whose sympathies with the poor of all nations seemed the first word of wisdom in international relations.