ireland s great war

Kevin Myers

the lilliput press

dublin

Contents

To the Forgotten Soldiers of Ireland, 191418

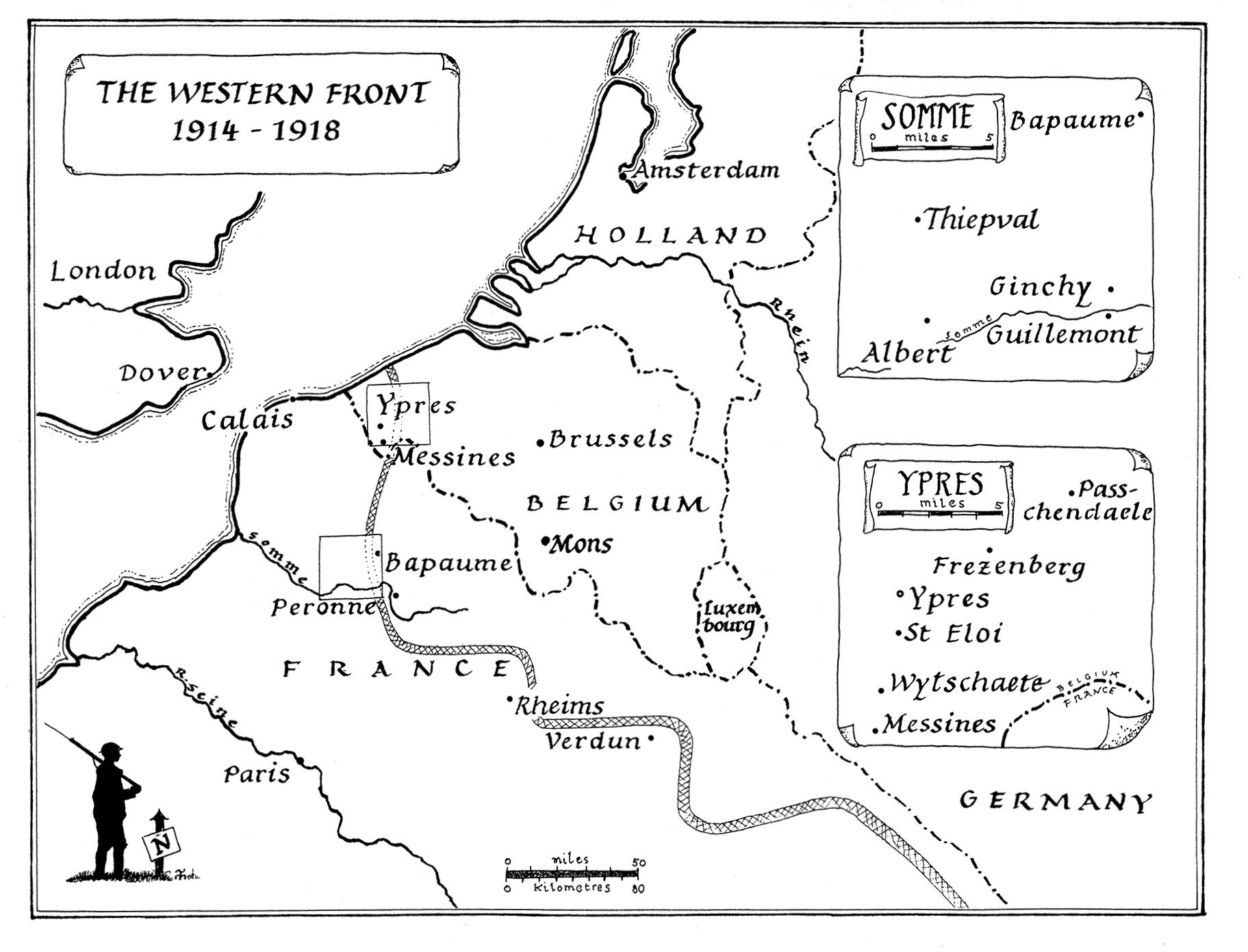

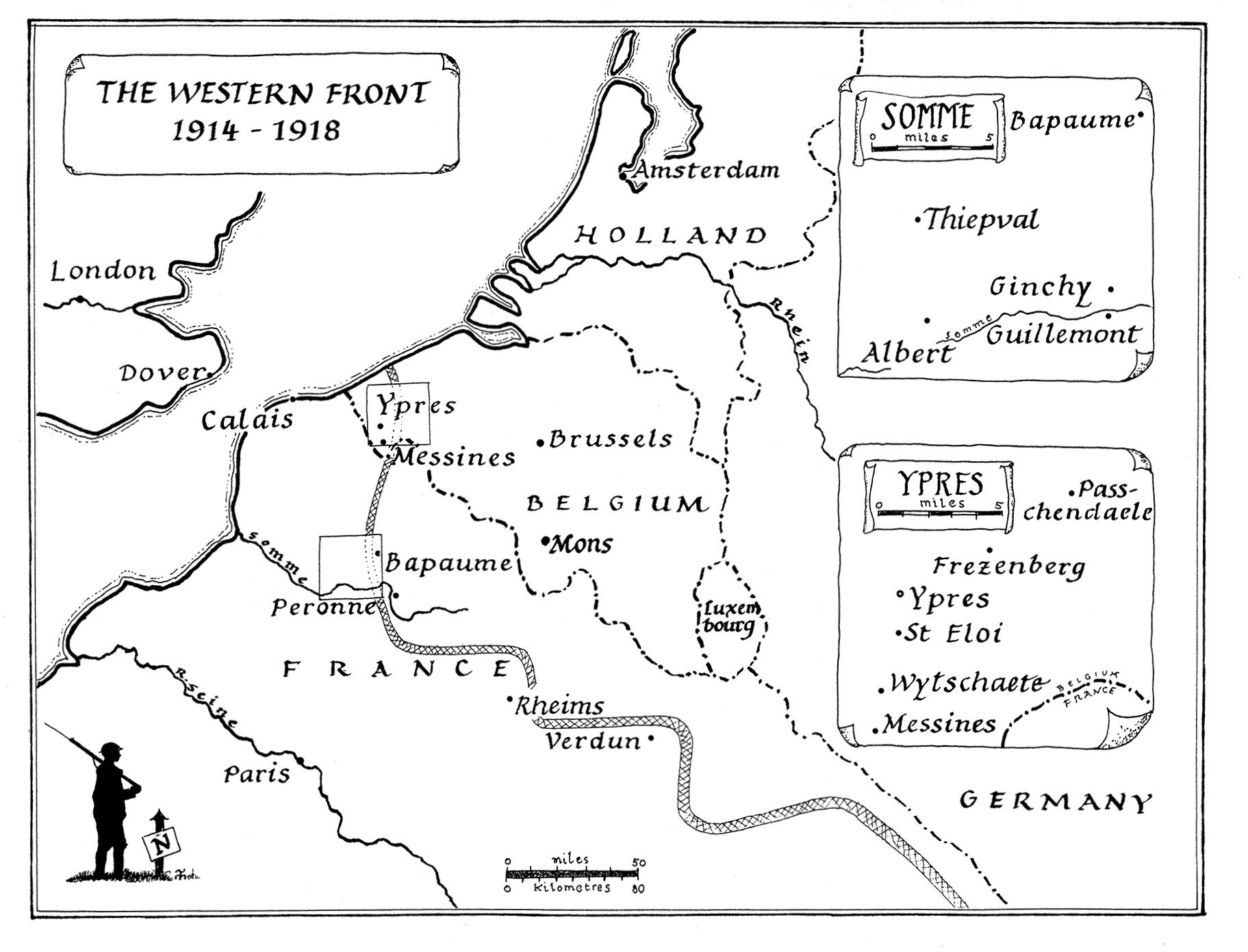

Map of the Western Front

by Tim ONeill

Introduction

The first time I went looking for the Memorial Gardens for the Irish dead of the Great War, almost no-one in Kilmainham seemed to know where they were. The year was 1979, sixty years on from the Treaty of Versailles and after the meeting of the First Dil, and the first shootings of the Anglo-Irish War (in which both sides were of course Irish). In 1919 Europe had gone one way, and independent Ireland had gone another, the journey of the latter taking it to a condition of utter amnesia about the very war that was central to its foundation-myths. For without the Great War, there could have been no Easter Rising, and no gallant allies to support it. Yet it had nonetheless been completely forgotten, and so totally that not merely had people forgotten, but theyd forgotten that theyd forgotten. So complete was the eradication of any knowledge of Irish involvement in the war, that yards away from the great park to honour Irelands war dead, no-one admitted to knowing of its existence.

Or maybe they just didnt think of it as a park, because by that time it had been turned into an urban tip-head, with Dublin Corporation lorries disgorging the citys rubbish onto vast mounds of spoil. A score or more tinkers caravans were parked on the edges of the park, and alongside them were the rusting hulks of scrapped cars. Piebald ponies grazed in the foot-high weeds, children scavenged through the waste, and Lutyens great granite columns were covered with graffiti. In the muck, almost invisible, lay the two elegant granite obelisks meant to represent lapidary candles, now felled, and almost invisible.

The plinth beneath the memorial obelisk declared then, and declares still, that 49,400 Irishmen died in the Great War. This foundation-falsehood has survived the decades, and is even now being recited as a fact by government ministers. It is simply could not be true, for with casualty-rates running at 11 per cent, this would imply that 500,000 Irish had served out of an island of under four million. However, the figure is an interesting example of how an attractive myth 49,400 gives the appearance of fact, because it is so close to 50,000, yet scrupulously isnt survives deconstruction.

As I cycled away from the tiphead that the park had now become, I made a vow to do what I could to get it turned into a decent park again. The first thing I had to do was to get the facts right so I spent months going through the Memorial Records that had been compiled in the early 1920s at a staggering cost (then) of 5000 to assess who was actually Irish amongst that 49,400. The records had been put together under a committee led by Eva Bernard, of a prominent unionist family, and it seemed that to put it mildly she wanted to maximize Irelands involvement in the war, and thereby maximize Irelands devotion to the union. So, the memorial records counted as Irish anyone who had served in an Irish regiment, regardless of where they were from. Admittedly, the question of who is Irish is not easily resolved. Many Irish people such as Willie Redmond MP , who was born in Liverpool cannot be called non-Irish simply because of their place of birth. Infuriatingly, one primary source for the Memorial Records and for all subsequent analysis of this time Officers Died in the Great War unlike the companion volumes, Soldiers Died in the Great War does not give the place of birth of the men it lists.

The figure I came up with, first published in a feature article in The Irish Times in November 1980 (see Opening Shots, p.19) was roughly 35,000. Such is the power of the press, and of my colossal influence therein, that this figure of 35,000 has had absolutely no impact whatever. Quite simply, people still prefer the mythic and perhaps Vedic: who knows? number of 49,400. But having since discovered the disgraceful War Office pension-saving policies of discharging injured soldiers from the army, and then not counting their deaths from war-related injuries as meriting a place in SDGW or ODGW , I feel 35,000 is too low. Furthermore, it is now clear that the military bureaucracy like the War Graves Commission, a generally meticulous organization determined to honour the dead was sometimes overwhelmed by the scale of the catastrophes confronting it. And this is understandable, for it had to record the same basic details for every single dead man: name, rank, number, regiment, battalion, cause of death, date of death, location of death, place of birth, place of residence, place of enlistment, decorations and former regiment. That is at least 240,000 separate facts for the 20,000 dead of the first day of the Somme alone, and without a pause for counting, because on the second day, there were 1438 dead, and on the third, 2338, and on the 135 th day, 13 November, there were 2504 dead; and from 1 July to 13 November, covering the duration of the Somme, there were 122,466 British dead alone, yielding at least 1,469,592 details to be recorded in S / ODGW . How does any organization, using just clerks with fountain pens and paper, manage such a feat, while all able-bodied men are being sent off to war? So, allowing for such human failings, I would now confidently say Irelands war-dead number 40,000.

Glimpsing such appalling statistics is, however, like a doctor peeling back a bandage, noticing a wound but then smelling gas-gangrene, for theres far worse than you can see. It has been the besetting sin of belligerent Anglophone countries, in which community Ireland has now claimed full membership, to see matters only through their own experiences. On 22 August 1914, the very day that the 2nd battalion, the Royal Irish Regiment suffered their first casualties near Mons, 27,000 blue-coated, red-trousered French soldiers were killed, in the first day of the Battle of the Frontiers. The cult of the uninhibited offensive loutrance was now treading out its daily harvest of garnered youth through the wine-press of war. By 29 August French losses totalled 260,000, with 75,000 dead. The British army never had a week like that or even a month in the entire war.

Consider the night-assault by the Ottoman army, starting on Christmas Eve 1914, at Sarikamish high in the Caucasus. At minus 35 degrees Celsius, the troops had been ordered to discard their greatcoats and backpacks for greater speed. Some 25,000 men disappeared in the advance, and those not butchered by the waiting Russians froze to death in the rout that followed. The Russians found 30 ,000 bodies in the snow, and another 25,000 wounded apparently dragged themselves away and perished on the mountainside. That is, over 50,000 men froze to death over a just a couple of nights. Come the spring thaw, the wolves of the Caucasus grew exceeding fat.

Sacrifices like this could only have been possible if human attitudes, and especially those of men, were unrecognizably different from what we know today. This was true of all nations. Ludwig Frank, a Socialist Deputy in the Reichstag, who had feverishly (and successfully) lobbied for his party to abandon its pacifist policies and support of the war, wrote on 23 August: I am happy; it is not difficult to let blood flow for the Fatherland, and to surround it with romanticism and heroism.

Frank was a Jew, and was the only Reichstag Deputy to die in the war, whereas three Irish MP s two nationalist and one unionist were to die. (Lt Tom Kettle of the Dublin Fusiliers who is often cited as an MP was no longer a member of the House of Parliament when he was killed at the Somme.) Even that most clinical of Austrians, and Franks fellow-Jew, Sigmund Freud, admitted to the almost insuperable power of what he called the libido that he felt for his homeland. Yet what perhaps distinguishes Ireland most from all of the subject territories in what, after all, was an imperial war, or rather, wars, was its exemption from conscription. Poles were especially lucky, for, depending on where they lived, members of an extended family could be forced to fight for the Romanov Tsar and the Hohenzollern Kaiser and the Habsburg Emperor. On mobilization, Czech conscripts marched away bearing (the rather-Czech) banners, declaring, We are marching against the Russians and we do not know why. They were not the only unhappy soldiers that summer. Dublin gunners on exercise in Athlone in early August 1914 , demonstrated, in uniform, against the Bachelors Walk shootings in Dublin, but they of course were not conscripts. Moreover, public anger at the shootings seems to have been largely dissipated with the public enquiry that followed within a fortnight, and which resulted in the now forgotten dismissal of the Deputy Head of the DMP who had illegally mobilized the army, and in the instatement of policemen who had mutinied rather than obey what they considered illegal orders. The only political demonstrations of Irish soldiers from that point onwards were by groups of uniformed Dublin Fusiliers in the pubs and streets of Naas in September 1914, celebrating the passage of the Home Rule Bill into law. These nationalists would then of course serve and die for crown for which many felt little or no loyalty, and would duly be forgotten by all.