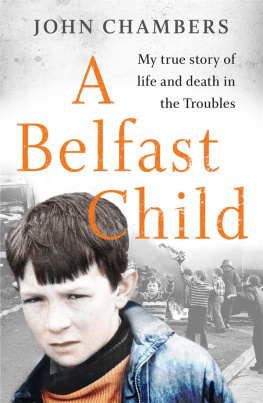

WHY WRITE about events that occurred so long ago, at such a terrible time in our countrys history and in a place few outsiders even now really want to visit? The answer is simple. This was a defining period of my life, and the secrets that it disclosed have been locked within me ever since. I saw murder face to face and heard the keening of bereaved and broken hearts. I witnessed the bloody chaos that results when the tribe is exalted over the individual, and when personal morality is abandoned to the autonomous ethos of some imagined community, independent of God and law. Moreover, the publication, in 1999, of David McKittricks majestic Lost Lives provided me with both the moral compulsion and the documentary material to set my fingers to the keyboard.

The resort to violence in Irish life is still celebrated by people who call themselves constitutional politicians. It is my hope that those who read through these pages will understand something of the reality of what violence does. This is why I have related the names of so many victims. Their deaths were the result of the failure of politics, but more crucially for me, each death formed a tiny brick in the edifice that was my earlier life. Their tragedy was my income. That is how I made my living, the beetle in the sarcophagus.

My sarcophagus had initially been the Protestant state for a Protestant people, which mirrored the Catholic state for a Catholic people that was the Irish Republic. However, such simplifications mislead. Senior judges and police officers in both Northern Ireland and the Republic were of the minority faiths. Contrary to subsequent fable, Catholics enjoyed the same voting rights as Protestants, but gerrymandered constituencies diluted their voting power. Most of all, Northern Ireland oozed a smug Unionist sense of power, and it was that which most riled Catholics. However , nothing about that state, or the conditions of its minority, justified the murderous calamity that befell its inhabitants during the years I write about, and those that followed.

This book is also about a naive young man in pursuit of the adrenaline of war and that cocktail of hormones accompanying love and sex. During the 1970s I behaved like young men have always wanted to, and always will. I have been as frank about this as possible. The truth does not, as the battle hymn of another republic declares, make us free, but at least it enables us to see where evil lies a little more clearly. If anyone finishes this narrative with a slightly sharper moral eyesight about the wickedness and folly of political violence on this island, then what follows will not have been wholly in vain.

I owe an unpayable debt to the many people who feature in this account of my life in Belfast. But for the purposes of this book, I want to thank my editor at The Lilliput Press, Mary Cummins, and of course Rachel, my wife, my rock and my love at all times.

David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney and Chris Thornton, Lost Lives (Mainstream Publishing; Edinburgh 1999).

July 1972

DRIVING SLOWLY up Shaws Road, Belfast, on a rare and lovely summers day: the sun radiant, the sky a Corsican blue. To the left, in the distance, an army foot patrol coming downhill towards me, threading its way in incongruous olive-fatigues past an urban-jungle barricade of ancient, burnt-out cars, dodging the bottles and bricks from clusters of shrieking children. Much closer and to the right, behind a block of flats and invisible to the soldiers, an excited group of feral teenage males seethed like primates. Farther to the right, a bucketing car skidded to a halt, the din of its arrival concealed by the noise of the riot.

I stopped, put on the handbrake and watched. The soldiers continued to advance in a single green faltering line. The car-driver leapt out and opened the boot, a triumphant Santa Claus at the back of his summer sleigh, to reveal his presents a Garand semi-automatic rifle, a couple of M1 carbines, some handguns. They were distributed, in no apparent order, and the teenage gang instantly and intuitively dispersed to their various firing positions.

I had chanced upon an IRA ambush. Slowly, I drove off right, within the lee of the flats, from where I could still see most of the soldiers. They were stumbling forward, sweating, confused and clearly reluctant outsiders from England, barely out of their teens and in a strange and hostile place. Stones whistled past their ears as capering children taunted them.

Directly in front of me was a bone-thin lad with an M1 carbine and his back to the wall. He was wearing a blue plaid shirt and blue jeans cut off above the ankles, and his dank, unwashed hair hung in curls. He stuck his nose around the corner, so he could peer right, towards the soldiers who still remained within sight. His head came back and he waited, his back rigid against the wall. His lips moved, as if he were counting. I opened my car door and stole sidewards, and kneeling, turned on my tape recorder.

The foot patrol drew closer, through shimmering heat waves rising from tarmac thinly puckered with the acne scars of recent vehicle fires. The air reeked the rancid smell of burnt rubber and seared steel now as ubiquitous in Belfast as coal dust in a mining town. From nearby hills came the rattle of pebbles in a drum, echoes of gunfire from odd skirmishes around the city. The IRA ceasefire had ended a couple of days before, and bloodshed had vigorously resumed, as if making up for lost time. In nearby Ballymurphy , paratroopers had gunned down half a dozen people, one by one, each casualty a lure for the next vain-helper, who in turn had been shot, the icing on their cake a priest they finished off as he administered the last rites to their penultimate victim.

There was no mercy on the streets that hot July day. The boy in front of me peered around the corner again, and drew back. The soldiers were still not quite close enough. He was good. He looked around, checking his rear, seeing but certainly not registering me as an enemy, then he cocked his weapon and swiftly turned, stepping sharply leftwards to give himself a clear field of fire from his right shoulder.

His carbine barked bang! bang! bang! bang! prompting supporting fire from the other, now invisible youngsters. The lead soldier collapsed in the middle of the road, falling vertically, his bones turned to water, and the rest of the patrol vanished behind cremated cars, rubble, lamp posts, anything. In front of me, the gunman had returned to cover, his back to the wall. From not far away, children whooped at the sight of the motionless heap in the middle of the road. The wounded mans fellow soldiers did not return fire. They had no visible targets, other than the infants mocking their fallen comrade.

A second soldier began to crawl from cover towards the body, triggering a fresh though undisciplined fusillade from my boy and half a dozen other positions, bullets striking in little puffs all around the soldier. His leg jerked, an arterial leap of blood from his thigh a moment later confirming the hit.

Two squaddies down; yet still no return fire from the rest of the foot patrol, apparently paralysed where they lay huddled under cover. The first soldier was hit several more times: with each strike, his body appeared to be plucked, as if by a large invisible bird, while the children exulted. This had the makings of a real massacre. Now even the gunmen were cheering, the lad in front of me almost out of hiding, brandishing his carbine like an Arapaho at his war dance.