Published in 2018 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2018 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. and Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Andrea R. Field: Managing Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Heather Moore Niver: Editor and Photo Researcher

Nelson S: Art Director

Tahara Anderson: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Loria, Laura, author.

Title: The Mexican-American War / Laura Loria.

Description: New York : Britannica Educational Publishing, in Association with Rosen Educational Services, 2018 | Series: Westward expansion: Americas push to the Pacific | Audience: Grades 58. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017018665| ISBN 9781680487695(eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mexican War, 18461848Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E404 .L88 2018 | DDC 973.6/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018665

Manufactured in the United States of America

Photo credits: Cover, p. 32 DEA/G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images; p. 5 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; p. 9 Pat Eyre/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 11 Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (reproduction no. LC-USZ62-21276); p. 13 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Digital file no. cph 3g02133); p. 14 Universal Images Group/Getty Images; pp. 17, 27 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; p. 18 Art Collection 3/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 21 Printed Ephemera Collection; Portfolio 198, Folder 4Rare Book and Special Collections/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (rbpe 19800400); pp. 22, 30 Hulton Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 24 Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; pp. 25, cover and interior pages (banner) Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division; p. 29 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (cph 3b50618); p. 33 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (file no. LC-USZC2-1948); p. 34 M.Sobreira/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 37 Library of Congress/Corbis Historical/Getty Images; p. 39 Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 41 Print Collector/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 42 Bettmann/Getty Images.

CONTENTS

Chapter One

The Story of Texas

Chapter Two

Texas Statehood Leads to War

Chapter Three

Fighting in Mexico

Chapter Four

Path to Victory

Chapter Five

When the Dust Settled

I n the early days of the United States, the nation was frequently engaged in conflict of one kind or another. There were wars to establish and defend Americas independence, such as the American Revolution and the War of 1812. There were conflicts with Native Americans, a result of the countrys desire to expand its territory. The Mexican-American War (18461848) was a conflict between neighbors. What began as a border dispute in Texas led to massive bloodshed for Mexico, huge land gains for the United States, and a damaged relationship between bordering nations.

Why did Americas hunger for land require going to war? Part of the answer lies in the concept of Manifest Destiny. This was the nineteenth-century belief that it was Americas divinely assigned mission to expand westward across North America and to spread democratic and Protestant ideals. John OSullivan, a journalist, coined the phrase in an 1845 newspaper editorial about the annexation of Texas, in which he spoke of Americas manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our multiplying millions. The roots of the concept, however, can be traced to American and European writers of the colonial period and even earlier who professed the belief that the replacement of the pagan practices of American Indians in the West was no less than an ordination from God. The term was used as justification for the US acquisition of territory all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

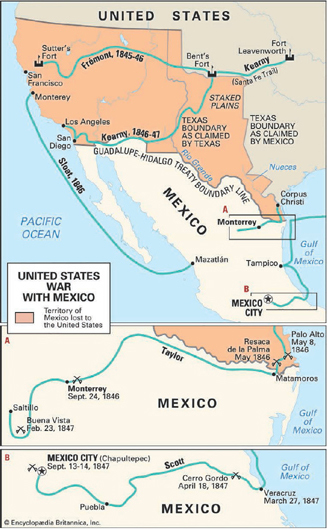

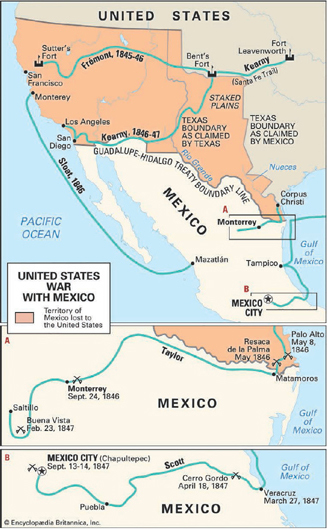

A dispute over the border of Texas led to war between the United States and Mexico in 1846. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which ended the war in 1848, gave the United States a vast tract of Mexican territory extending to the Pacific Ocean.

Another motivation for the Mexican-American War was economic. The Mexican territories of New Mexico (which, at that time, included much of what is now the southwestern United States) and, especially, California were very desirable to the United States. The US population was growing, and people needed places to live, farm, and conduct business. California also offered valuable harbors on the Pacific coast. Many Americans had moved to these areas already, and they wanted the land to be ruled by the United States. Even many of the Mexican residents of these areas welcomed American settlers. New Mexico and California were the Mexican frontier, and their sparse populations were constantly under threat from surrounding American Indian peoples. The Mexicans saw American settlers as potential allies against the Indians.

Related to economics was the issue of slavery. Using slaves to work on farms was far less costly than hiring help, and the practice was common in the southern United States. Many farmers in Texas and across the Southwest wanted to use slave labor, but the practice was outlawed in Mexico. In the United States, though controversy over slavery was growing, the practice was still permitted. For supporters of slavery in the western territories, becoming part of the United States was in their best interest.

Although Congress overwhelmingly approved a declaration of war against Mexico, not all Americans were on board. A number of people and groups were outspoken in their opposition to the conflict. The Whigs, a prominent political party, felt that the desire for the land was greedy and the declaration of war unconstitutional. Abolitionist groups worried that if the new territories were admitted to the Union as slave states, their struggle to end slavery wouldnt succeed. Abraham Lincoln, then a first-term Whig congressman from Illinois, argued that the war was unnecessary and unjustified. American author Henry David Thoreau was briefly jailed for failing to pay taxes, which he said was a protest against the war.

The Mexican-American War itself was brief, lasting just two years. It is often just touched upon in the study of American history. For both Mexico and the United States, however, the effects of the war last to this day.

T he story of the Mexican-American War begins with the history of Texas. In the eighteenth century, Texas was under Spanish control. Although the United States and Spain had some conflict over the borders between their territories, Spain had control of the area by 1819, confirmed by the Transcontinental (or Adams-Ons) Treaty. After Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, the boundary was confirmed by a treaty with the United States.

Inviting the Americans

Few Mexicans wanted to move to Texas, which was a remote and isolated region. The Mexican government was deeply in debt following the fight for independence, and it couldnt spare many resources for the northernmost part of the country. The Mexican government decided to allow Americans to settle in the area.