Preface

The American GI Forum (AGIF) celebrated its sixtieth anniversary in March 2008 at its executive board meeting in Corpus Christi, Texas, and again in September at its general meeting, also in Corpus Christi. I had the unique privilege of organizing a day-and-a-half symposium of scholars who had written on the history of the AGIF as part of the March meeting. Born of the discrimination of the early twentieth century, the groups founding members marked a new direction in an ongoing struggle for equality in the United States of America. Building upon a growing sense of patriotism and belonging, AGIF members, both singly and in partnership with other groups such as the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), began a renewed effort to ensconce their people in society, promote education for Mexican American youth, end jury discrimination, gain representation on draft boards, and otherwise integrate themselves as contributing and equal members of American society. These actors wanted to claim their rightful place as first-class citizens on all fronts.

The panel of scholars gave back to the forum members their understanding of the groups history. I was struck by the Forumeers animated spirit in engaging the speakers during that interchange. Agreeing with some of the speakers points and contesting others, I was impressed by the depths of the seriousness of the approximately fifty or so executive board members who attended our sessions. They made the panelists and me keenly aware of the significance of the history we all write. Sometimes scholars get so wrapped up in speaking to each other that we overlook the importance of historical actors themselves. This audience did not let that happen. Questioning our interpretations and asking questions in order to clarify our facts, they kept us honest and helped us hone our own understandings of their past.

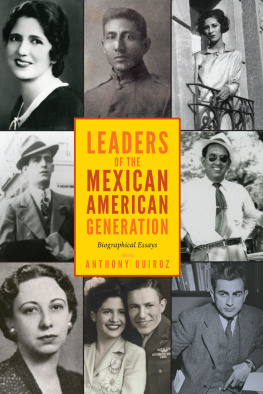

Prior to the symposium I had been toying with the idea of putting together a collection of biographical essays featuring key leaders of what some Mexican American scholars refer to as the Mexican American Generationa period bounded by the years from 1920 to 1965. My experience at the symposium convinced me to pursue this project. I asked all of the panel members to contribute to a collection of such pieces. Some agreed and appear here (Michelle Hall Kells, Carl Allsup, Tom Kreneck, Pat Carroll, and myself). Others had too many other prior commitments and, unfortunately, could not take part. I then embarked on a long process of seeking other contributors. Cold calling some folks and asking contributors for leads to others, I sought to gather a group of research that would showcase the contributions and significance of this generation of Mexican American activists, all of whom deserved to have their stories told.

In conducting this search I looked for works on the obvious key players of this period: J. Luz Senz, Alonso S. Perales, Alice Dickerson Montemayor, Jovita Gonzlez Mireles, Luisa Moreno, Flix Longoria, Hctor P. Garca, attorney Gus Garca (no relation to Hector), Vicente Ximenes, Eduardo Roybal, John J. Herrera, Ralph Estrada, and Ernesto Galarza. While by no means comprehensive, this is a respectable list of contributors to the ideals and actions of this generation. Their arguments, their worldviews, and their actions all shaped the character and identity of this generation. Whether arguing in court, writing, producing reports for governmental agencies, organizing workers, holding public office, forming new associations, or otherwise resisting the status quo, these individuals identified both the core values and the foci of the generation while also demonstrating its diversity.

I would like to thank all the authors for their contributions to this collection. I would also like to thank my editor at the University Press of Colorado, Darrin Pratt, and his wonderful staff, especially Jessica dArbonne, Laura Furney, and Diane Bush. Also helpful in conceptualizing this anthology were Linda Kerber, Arnoldo De Len, Carlos Blanton, and David Blanke as well as the anonymous readers for UPC. All of their comments on this manuscript made it vastly better. I owe a debt to the fine staff at the Houston Metropolitan Research Center and to Michael Rowell, Ceil Venable, and especially Grace Charles of the Special Collections and Archives at the Mary and Jeff Bell Library at Texas A&M UniversityCorpus Christi for their assistance. I would also like to thank my colleagues at Texas A&M UniversityCorpus Christi for being so patient with a part-time chair as I put the finishing touches on this work. As importantly, I would like to thank the contributors for their dedication and patience to this project even when it appeared as if the project might not be able to be completedfor reasons they understand. I would also like to thank Erin Cofer, a bright, talented graduate student in our program, for all her editorial and typographical help. Finally, I would like to thank my loving wife for putting up with my crankiness as this work wound down to completion. She is truly an angel on earth.

Introduction

ANTHONY QUIROZ

The serious, scholarly study of Mexican American history is a relatively recent development. Begun by a handful of researchers in the 1920s, the field grew slowly through the 1950s and expanded rapidly after the 1960s to the present. Through their research, scholars of the Mexican American historical experience have both contributed to our understandings of historical processes and discovered new directions for historical inquiry. Their findings have shed light on the broader sweeps of American history by showing the symbiotic relationship between Mexican Americans and the rest of the country. Mexican Americans were generally ignored, marginalized, and disrespected in the traditional canon of American history until the late twentieth century. But as their numbers grew, so too did the number of scholars interested in studying them. Mexican Americans have now become more firmly entrenched in scholarly discussions about historical issues such as race and ethnicity, gender relationships, class, politics, education, economics, culture, and in an ongoing negotiation of the meaning of American. This book contributes to that growing body of literature by providing students of Mexican American history with a compilation of biographies of key Mexican Americans active from about 1920 through the 1960s. The purpose of this work is to offer readers a concise biographical overview of some of the actors who made Mexican American history during this period and to cast them in the context of their times in order to shed light on the historical significance of their contributions.

The folks who became socially active during this period inherited a social climate of hostility based on deeply rooted, pervasive racism. Anti-Mexican sentiments were born in the nineteenth centuryfirst in Texas in the aftermath of the Texas Revolution against the Mexican government in 18351836 and across the entire American Southwest after the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. Gradually dispossessed of their land, Mexican-descent farmers and ranchers experienced downward mobility throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Poor trabajadores (workers) remained mired in an economic system that disallowed opportunities for upward mobility. Anglo employers saw them as lazy, incompetent, and dishonest, and they relegated these laborers to low-wage, low-skill manual jobs. Those with agricultural skills could find work on farms and ranches. With the loss of land and opportunity came a degraded social and political status. Mexican Americans had been successfully relegated to second-class citizenship by 1900.