This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2017 by Allen D. Boyer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68247-097-8 (eBook)

Maps created by Beth Robertson, Mapping Specialists Ltd.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

To Margaret Anne Boyer

To Margaret Anne Boyer

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

Photos

Maps

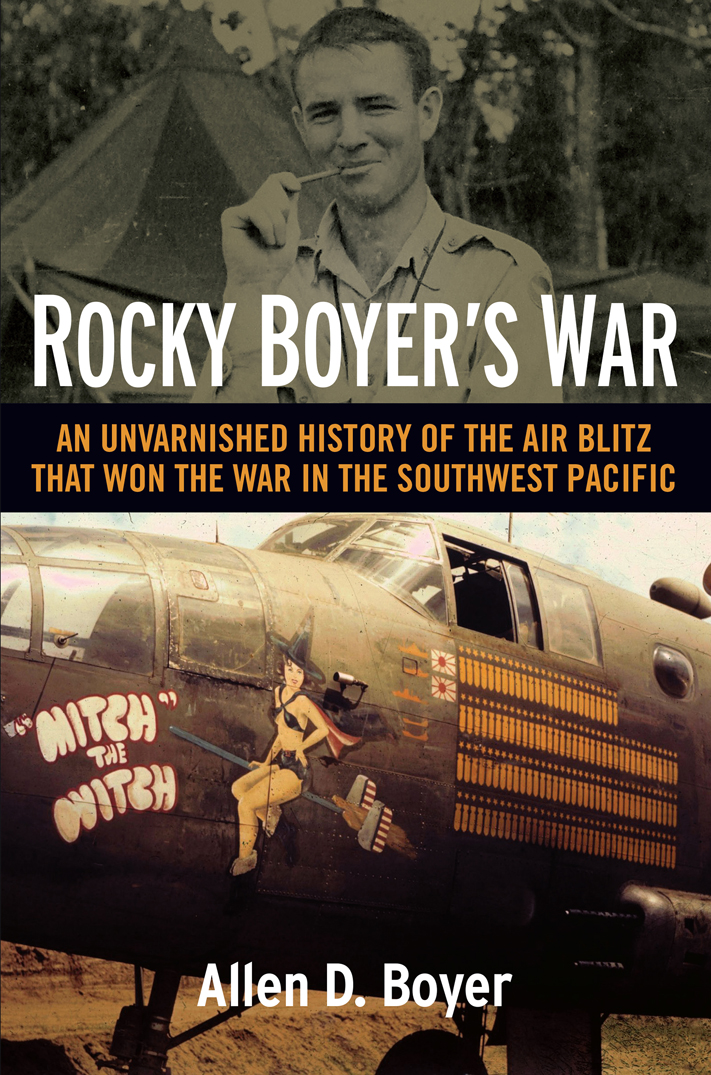

This book follows and draws on a diary kept by Lt. Roscoe A. Boyer, my father, during his service in the Southwest Pacific. This diary is currently in my possession. The book reflects my fathers own experiences and readings of eventshis opinions and recollections. To frame or expand on what he wrote, I have used other material, primary sources where possible: unit histories, Missing Air Crew Reports, service newspapers, stateside newspapers, and commanders memoirs. Sometimes I have verified what he reported, other times clarified or corrected it; but my father speaks in his own voice. His assessment of events he witnessed and people he encountered is unflinching (and at times unflattering), and his observations are presented as he recorded them during his time in the Pacific. Spelling and usage have been modernized and standardized. My father wrote grammatically and spelled well, but he constantly used abbreviations, frequently printed whole entries in block capitals, never indented a line or broke for a paragraph, and sometimes wrote as carelessly as some people type.

Writing seventy years ago, in the middle of a war, my father wrote of the enemy as Nips or Japs, offensive slurs. This was the language of the military in which he served; it has not been changed. He himself did not use those terms with mockery or contempt. He considered that the Japanese fought with courage and intelligence, and if he armed warplanes that flew against them, there were times when he thought he might die at their hands.

The only people to whom my father ever applied a disrespectful epithet were West Point graduates. Ring-knockers, he called them, after their customary way of calling a meeting to order.

Half an hour before midnight, the first Japanese shell exploded overhead. It was a star shell, a sudden smear of blinding white light against the black night sky, and the scorching glare lit up the airfield. The bomb craters in the runway. The tanks of aviation gas, drained dry. The gray smoke above the fire in the bomb dump. The control tower and the banged-up bomber and the burning wreck of the fighter plane. The brass shell-casings fired off by the antiaircraft guns. And on the tarmac, a scattering of silhouettes and shadows: the handful of Fifth Air Force men and the empty bomb trolleys they were wheeling back into cover.

They were the airmen of the 71st Tactical Reconnaissance Group. Reconnaissance meant that they flew patrols looking for the Japanese. Tactical meant that if they found the Japanese, they bombed and strafed them. This evening, things were spun around: the Japanese had moved first and gotten too close. For once, the airmen knew exactly where the Japanese were. What they did not know was whether they could stop the Japanese warships before the Japanese found the range and brought their guns to bear on the airfield.

All that evening, in the dark, they had worked to arm the planes. They had sent out every bomber and fighter-bomber that could fly, carrying every bomb they could find and find fuses for. Not all of their planes had come back and some that did had been shot full of holes. None of that had made a difference.

For three long hours now they had watched the Japanese warships come south along the coast toward them. They had seen searchlights and ripples of flame and sometimes a swarm of firefly lights in the darkness. The firefly lights were their own bombers running lights, and the ripples of flame were enemy antiaircraft guns, shooting at the bombers. No matter what their planes had done, the Japanese ships were still coming south.

They were in the Philippines, on the island of Mindoro. It was 1944, a hot dry evening, the day after Christmas.

Since the year began, they had fought their way northfrom New Guinea to the Philippines, two thousand miles of mountains, jungle, islands, and oceans. In the Fifth Air Force, they had been the artillery for Douglas MacArthurs army, and sometimes the tank corps too. The airfields had been the front line. They had made rough landings in valleys where airfields could be built, flown in squadrons of warplanes while the Japanese were still being cleared out, and moved the front line forward. They had sidestepped entire Japanese armies and cut them off and left them behind, sitting on empty islands. They thought MacArthur was an ass, but he hadnt made many mistakes and he hadnt gotten them slaughtered on beachheads.

Mindoro was close to the Japanese and far from helpthis time, MacArthur might have made a mistake. They were three hundred miles from the Sixth Army divisions on Leyte, farther still from any friendly air base, nowhere near any Navy fleet. They would have to handle, by themselves, whatever the Japanese threw at them. At their last base Japanese paratroopers had landed on the runway, shouting Banzai! and firing submachine guns. That recollection was on everyones mind. Tonight the radio section was talking about a convoy of enemy troopships. One bomber pilot had seen landing barges alongside the destroyers. Against paratroopers with submachine guns all they had would be their pistols, and against the Japanese cruisers their bombers didnt seem to have done much good. If the Japanese warships were firing star shells now, they would be firing high explosive shells next.

That night on Mindoro, Rocky Boyer1st Lt. Roscoe A. Boyerwas one of the officers loading the bombs. He was my father. Rocky was twenty-five then. In his young life he had been a farm boy, a college boy, a draftee, and a sergeant, and now he was communications officer for the 110th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron. The next day, out of the officers in his tent, he would be the only man left alive.