Table of Contents

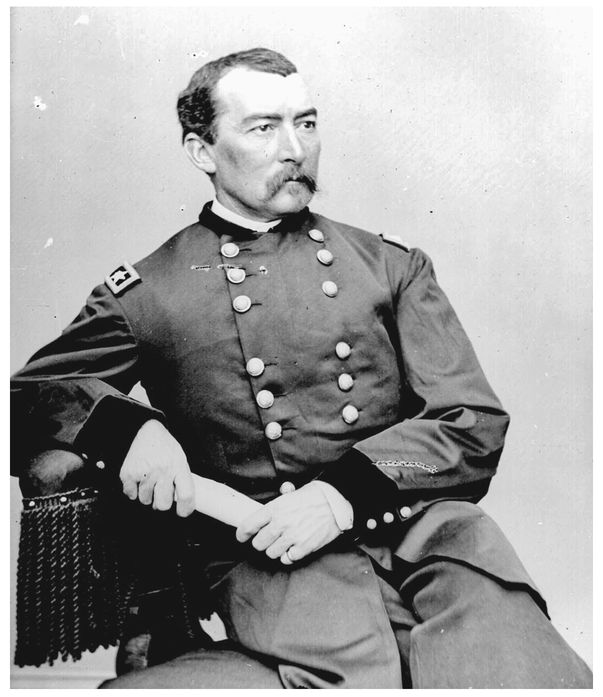

Major General Philip Sheridan. National Archives

In memory of the late

EDWARD W. KNAPPMAN

(NOVEMBER 1943MARCH 2011)

a first-rate literary agent, editor, and mentor

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

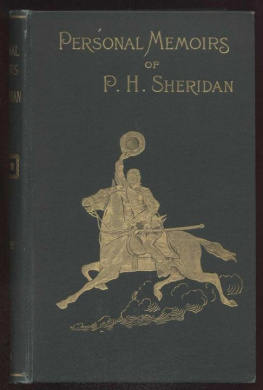

The genesis of this book was a two-volume set of Philip Sheridans Personal Memoirs that came to me after my fathers death. For years, it sat neglected on the shelf while I pursued a career and wrote books about the early nineteenth century.

When I finally got around to reading the Personal Memoirs, I realized that Sheridan would make a fine subject for a book.

As I delved more deeply into Sheridans life and times, librarians and historians from Washington, D.C., to Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina aided me in tracking down the information that I needed to write this book.

The University of North Carolinas Davis Library and its Southern Historical and Rare Book collections offered a rich trove of Civil Warera diaries, journals, and papers.

During my visits to the Library of Congress in Washington, the staff, as always, was courteous and eager to assist.

Wake County Public Librariesparticularly the Interlibrary Loan staff and the West Regional Libraryhelped me to obtain microfilms of Philip Sheridans papers lent by the Library of Congress.

The staff historians at the Civil War battlefields where Sheridan became a household name were generous in sharing their valuable knowledge with me.

Jimmy Blankenship, the historian at the City Point Unit of the Petersburg National Battlefield, guided me through General Ulysses S. Grants City Point headquarters, and answered my questions about Sheridans and President Abraham Lincolns visits in 1864 and 1865.

James Ogden, historian for the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, clarified Sheridans movements during the Battle of Chickamauga.

Finally, my wife Pats unflagging support and interest were as essential to this project as to every historical journey that I have undertaken.

They want war too methodical, too measured; I would make it

brisk, bold, impetuous, perhaps sometimes even audacious.

ANTOINE HENRI JOMINI

PROLOGUE

OCTOBER 19, 1864WINCHESTER, VIRGINIAMajor General Philip Sheridan and his three-hundred-man escort rumbled through the streets of the oft-captured strategic crossroads city in the early morning. All around them, the Shenandoah Valley was ablaze with vivid autumnal yellows and reds under a serene, blue sky. It might have been a glorious day for picnickingexcept for the disturbing sound of distant cannon fire.

After an absence of three days, Sheridan was returning to his Army of the Shenandoah. His 32,000 veterans were camped to the south among an accordionlike series of ridges along the north bank of Cedar Creek. On the creeks other bank, Massanutten Mountainand, significantly, Three Top Mountain, with its Confederate signal stationloomed over the Union encampment.

Sheridan had been in Washington to confer with War Secretary Edwin Stanton and Army Chief of Staff Henry Halleck about his armys next move. They liked his plan to send most of his men to General Ulysses S. Grant at Petersburg, leaving just a small force at the Valleys north end to check any Rebel advances.

Major fighting in the Valley seemed at an end. In September, Sheridans army had defeated Lieutenant General Jubal Earlys Army of the Valley at the Third Battle of Winchester and then, three days later, had driven the Rebels from Fishers Hill. The Confederates had withdrawn seventy miles to the south, to Waynesboro.

But then, on October 12, Earlys army had suddenly reappeared at Strasburg, just a few miles south of the Yankee positions. Sheridan had already sent VI Corps marching east to join Grant. He ordered it to return.

On October 16, Union signalmen intercepted a Rebel communication indicating that Lieutenant General James Longstreets I Corps was marching to Earlys aid. A courier had overtaken Sheridan on his way to Washington. After reading the message and obtaining intelligence on recent enemy movements, Sheridan concluded that it was a red herring (it was). But he was unable to rid himself of nagging second thoughts, and he had returned as quickly as possible.

When Sheridan left his army, the Rebels occupied Fishers Hill, about ten miles south of Cedar Creek.

But today the Rebels were no longer at Fishers Hill.

LIKE MANY CIVIL WAR generals, Sheridan had risen fast, after being stuck in rank at lieutenant for eight years in the peacetime army. He was still just a captain in 1862 when he was given his first field command, the 2nd Michigan Cavalry in Mississippi. His career had taken off with a series of battlefield promotions. He was now responsible for parts of three infantry corps and the Cavalry Corps.

In December 1862 at Stones River, Sheridans division had slowed the Confederate onslaught long enough to save Major General William Rosecranss Army of the Cumberland from destruction. In 1863, his division had reached the crest of Missionary Ridge first and pursued Braxton Braggs retreating army the longest. In May 1864, Sheridans Cavalry Corps had defeated the Rebel cavalry at Yellow Tavern and mortally wounded the celebrated Jeb Stuart.

When Jubal Early threatened Washington in July 1864, President Abraham Lincoln, General Ulysses Grant, and War Secretary Edwin Stanton decided that the Shenandoah Valley had to be cleared of Rebel armies. They combined four military departments and made Sheridan commander of some of the best fighting men in the Union army.

Sheridan had impressed Grant at Missionary Ridge and later, too, when he transformed the Cavalry Corps into a mobile strike force. He was increasingly seen as a man who got things done fast, a man who could think on his feet.

He was small, five foot five at most, and thin but wiry and broad shouldered; his men called him Little Phil. On horseback, Sheridan appeared larger because his torso and arms were disproportionately long, and his legs were short. He possessed incredible stamina that enabled him to function at a high level without sleep or food.