Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

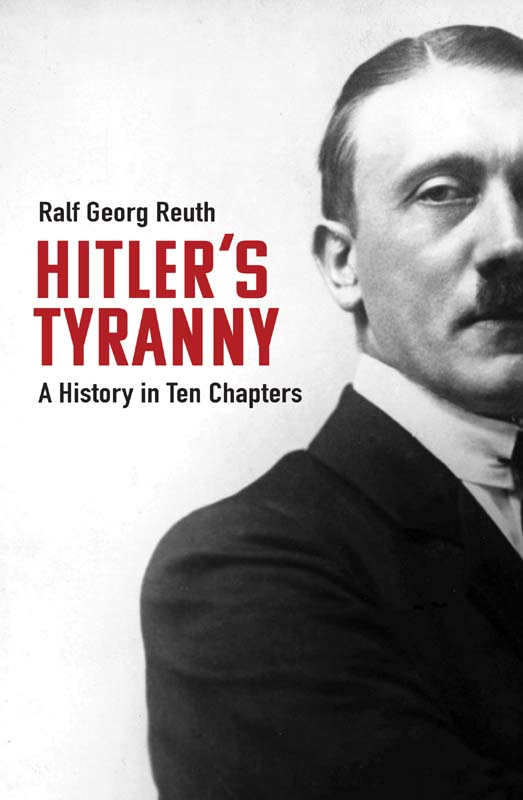

HITLERS TYRANNY

RALF GEORG REUTH

Hitlers Tyranny

A History in Ten Chapters

Translated from German by Peter Lewis

First published in English in 2022 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

4 Cinnamon Row

London sw11 3tw

First published in German as Hitler. Zentrale Aspekte seiner Gewaltherrschaft

Copyright Piper Verlag GmbH, Mnchen 2021

Translation copyright Peter Lewis, 2022

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

The moral right of the author and translator has been asserted

ISBN 978-1-913368-62-3

eISBN 978-1-913368-63-0

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by Clays

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

Introduction

This book has as its subject the darkest years of German history and the person whose name is synonymous with that period: Adolf Hitler. The Second World War, which his actions unleashed, visited destruction and millions of deaths upon humankind. Yet the gravest legacy of Hitler and his twelve years of tyranny was the monstrous industrialised extermination of millions of innocent non-combatants, a cataclysmic event encapsulated in the place name Auschwitz. The devastating psychological scars left behind by the genocide of Europes Jews will seemingly never heal. It shook the very foundations of civilization and, as a consequence, is of universal significance.

To a far greater degree than the Soviet Russian and the Chinese universes of destruction, as the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has dubbed the three great crimes against humanity in the twentieth century, the German genocide has become the focus of intense scrutiny and interest. Not least, this is the result of the Federal Republic of Germany having confronted its problematic past with a purpose and thoroughness not witnessed elsewhere, but it also has to do with the fact that the Jewish community in other words, the community which above all has a keen interest in appraising this phase of history is dispersed across the entire globe. The upshot of both these factors has been a wealth of literature on National Socialism, which in the interim has mushroomed to such proportions that not even those who deal with it in a professional capacity can keep track of it.

Looking back is always subject to change, since history is not a static phenomenon. Instead, it is conditioned by the changing face of contemporary politics. At seats of higher learning in the liberal democracies, especially those in Germany, this has resulted in historical research taking on an increasingly sociological character from the 1970s onwards. In the process, historical turning points are often glossed over and the significance of human planning, decision-making, and agency played down. This school of thought asserts that it is first and foremost societal structures that determine the course of history. This viewpoint has latterly been supplemented by an understanding of history that maintains that any recapitulative interpretations of past epochs are inherently unreliable. According to this view, historians can only recapitulate what individual sources tell us about the past. Alongside, and in response to, the sociologically dominated way of looking at history and deconstructivism on the internet far removed from the ivory towers of academe a new, negligible, and vulgar form of historical revisionism has taken root.

The common denominator of all these diverse historical viewpoints is that a substantive appraisal of the historical figure of Hitler has tended to recede further and further into the background. Even though a biographical approach is very hard to reconcile with a sociological viewpoint, this latter tendency has nonetheless still managed to find its way into this realm. Whereas the active personage of Hitler still stood front and centre in Joachim C. Fests great biography, which first appeared in the early 1970s,

Elsewhere, sociologically dominated historiography does not hold undisputed sway to the same extent as in Germany. In France, for example, there is a far more liberal contemporary historical discourse. Thus, the socialist historian Franois Furet, author of a definitive study of communism, The Passing of an Illusion,

Where the shaping of historical developments is concerned, this insight holds good in a negative sense for Hitler to a quite striking degree, since he was indisputably the figure who was most prominent in shaping the history of the twentieth century. He changed the face of the world like no one else. The end of old Europe as the centre of world power; the rise of the two opposing superpowers of the United States and the Soviet Union as heirs to this mantle of power; the dividing of the continent and of Germany; the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the reunification of Germany none of this would have occurred if Hitler had fallen on some battlefield during the First World War. Future generations are often completely unaware of this possibility.

In history, everything is connected with everything. Accordingly, it is all the more unhistoric for Hitler, and above all his crimes against humanity, to be wrested from their historical context something that is happening with increasing frequency. What results from this kind of insular thinking is a purely emotional response to the subject, which has already culminated simply in demands to dispense entirely with any historical account of the Nazi genocide on the grounds that such an approach attempts to make comprehensible something that is inherently incomprehensible and is therefore bound to fail. In this context, Joachim Fest, whose work set the tone for numerous subsequent interpretations of Hitler, just as Kershaws did later, spoke of a form of demonological displacement that encouraged myth-making and legends but in no way contributed to a greater understanding of what had taken place. To achieve such an understanding, the most essential requirement alongside a sober and objective treatment of the topic is to firmly embed it within the historical context of German and European history. This is the only way in which the political and moral dimension of Hitler can be properly gauged.

This historicisation, which prominent historians were already calling for even in the 1980s,before Hitler appeared on the political scene. Following on from this, we examine whether Hitlers rise to the chancellorship in January 1933 was only made possible by the unfinished revolution of November 1918 in Germany and the subsequent split in the German working class a view still espoused today by intellectuals of the Left. Since the end of the Second World War, the narrative from the opposing political camp has been that the Versailles Peace Treaty was responsible, thus shifting at least part of the blame for Hitler onto the victorious Allied powers in the First World War. But is this view truly tenable?

A major bone of contention among German historians in the 1980s was whether the genocide conducted by the National Socialists was a response to the class murder committed by the communists; this thesis was notably advanced by the historian and philosopher Ernst Nolte, and remains the subject of lively debate today. Moving on from this, we tackle the question of how a politician who advocated a fanatical form of racism and painted scenarios of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy was able to become chancellor of Germany. We also investigate why, in spite of his brutal elimination of all opposition and his racial policies, which displayed utter contempt for human rights, the nation swung behind him. Did the Germans simply take such things as part and parcel of his triumphal rewriting of the terms of the Versailles Treaty not least because they failed to understand this man with his overweening sense of destiny? Was it this same failure on the part of the German people to grasp reality that fostered a personality cult, allowing Hitler to style himself as some Wagnerian figure from another realm who offered the prospect of salvation?