This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING www.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books contact@picklepartnerspublishing.com

Text originally published in 1917 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

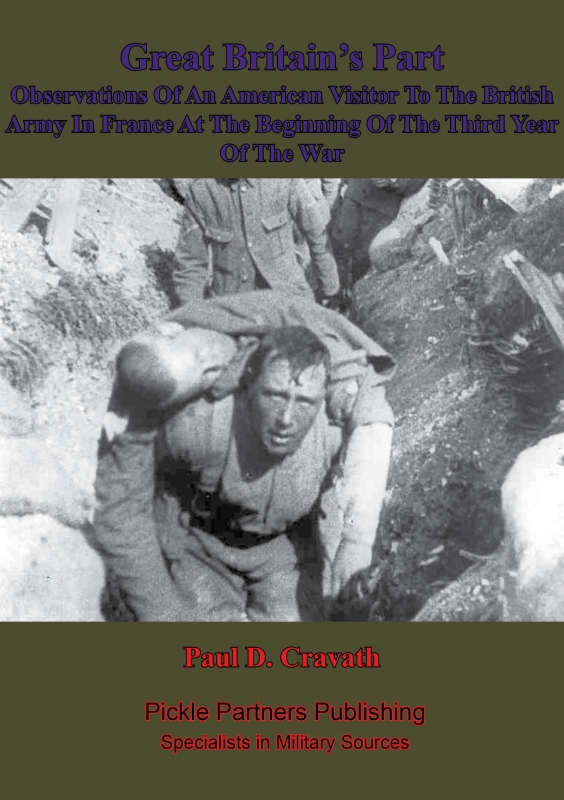

GREAT BRITAINS PART

OBSERVATIONS OF AN AMERICAN VISITOR TO THE BRITISH ARMY IN FRANCE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE THIRD YEAR OF THE WAR

BY

PAUL D. CRAVATH

GREAT BRITAINS PART

I

AN invitation to visit the British war zone in France came quite unexpectedly after I had spent the greater part of July studying war conditions in England. I had seen a good deal of the British army at home. I had visited recruiting stations, training camps, munition factories, hospitals, and camps for German prisoners. I had heard the conduct of the war discussed from every conceivable anglein the House of Commons, at public meetings, at the Clubs, around the dinner table, and at the street corner. Indeed, in London, one hears very little else. I had heard as much of criticism as of praise, doubtless because the critic usually has a taste for conversation and leisure to gratify it.

The more I saw of the army that was training in England, the keener became my ambition to see the army that was fighting in France. I had little hope of gratifying this ambition, because I had been told that, since the inauguration of the great Push, visits to the front by civilians were rarely permitted. Finally some good friends in the war office concluded that as I had heard so much in England from the critics, it would be worthwhile to send me to the front to form my own opinions.

What I saw so completely revolutionized my conceptions of the war, based on what I had been able to hear and read, that I have concluded that by publishing my impressions I may help other Americans to a better appreciation of the transcendent importance of the war and of the unparalleled scale on which it is being waged.

At the time of my visit I had no idea of publishing my observations. I accordingly made no notes and my knowledge of military affairs is very limited. I can therefore do little more than give my impressions.

II

IT would be hard to overstate the unpreparedness of England on that fateful fourth day of August, 1914, when she declared war against Germany. It will be to her everlasting glory that she responded so promptly to the call of duty without stopping to count the cost. She was not only wanting in all of the material preparations for war on land, but neither her government nor her people had any real conception of the colossal demands that the war would make upon the manhood and resources of the Empire. Anyone who has traveled in Germany or France can appreciate in some degree the magnitude of the task which confronted England, when he realizes that before she could really be a factor in the war on land it was necessary to build up a military organization in all of its manifold departments, practically equaling, in proportion to her population, the establishments which it had taken Germany and France half a century to create. She not only had to provide the material equipment for several millions of soldiers, such as barracks, training camps, ammunition factories, artillery, apparel, supplies of every kind and even the rifles which her soldiers were to carry, but she had the even more difficult task of arousing the war spirit in a people who from time immemorial had been trained in the occupations of peace.

How little the leaders of England realized what was before them is shown by the division of opinion in the Government during the first days of the war as to whether any army should be sent to France. Kitcheners first call was for only a hundred thousand men. The second call was for half a million. Even after the war had fairly started and the Germans were swarming before the very gates of Paris, less than half a million men were in training. The failure to make even a fair beginning in providing for the necessary munitions, until the lack of them was revealed by the terrific slaughter in the second battle of Ypres in the ninth month of the war, was due to the Governments inability to grasp the scale on which the war was being waged by Germany.

When one realizes all this, Englands achievements at the close of the second year of the war seem little short of miraculous. They certainly are without parallel in history. In two years, or, if one allows for the wasted first months, in less than a year and a half, while maintaining, and even enlarging in the face of serious losses, the greatest navy the world has ever known, England, with the aid of her colonies, created, trained, equipped and munitioned an army of considerably over four million men. Of this army approximately half a million were furnished by Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Most remarkable of all, it was chiefly a volunteer army, for conscription did not come until the war had lasted for over a year and a half, when from eighty to ninety per cent of the men of England, Scotland, Wales and Ulster and many from the rest of .Ireland had volunteered.

Although at the time of my visit the British were maintaining an army of about a million and a half men in France and at least half a million more in the East and must have lost three or four hundred thousand men in killed, wounded and prisoners, England was still a veritable armed camp. Soldiers were everywhere. Each district had its training camp. There were about two hundred thousand men in training on Salisbury Plain alone and as many more at Aldershot and at the training camps where the Canadian regiments were concentrated. There were probably between a million and a half and two million soldiers in various stages of training throughout the United Kingdom.