Natures of Colonial Change

NEW AFRICAN HISTORIES SERIES

Series editors: Jean Allman and Allen Isaacman

David William Cohen and E. S. Atieno Odhiambo, The Risks of Knowledge: Investigations into the Death of the Hon. Minister John Robert Ouko in Kenya, 1990

Belinda Bozzoli, Theatres of Struggle and the End of Apartheid

Gary Kynoch, We Are Fighting the World: A History of Marashea Gangs in South Africa, 19471999

Stephanie Newell, The Forgers Tale: The Search for Odeziaku

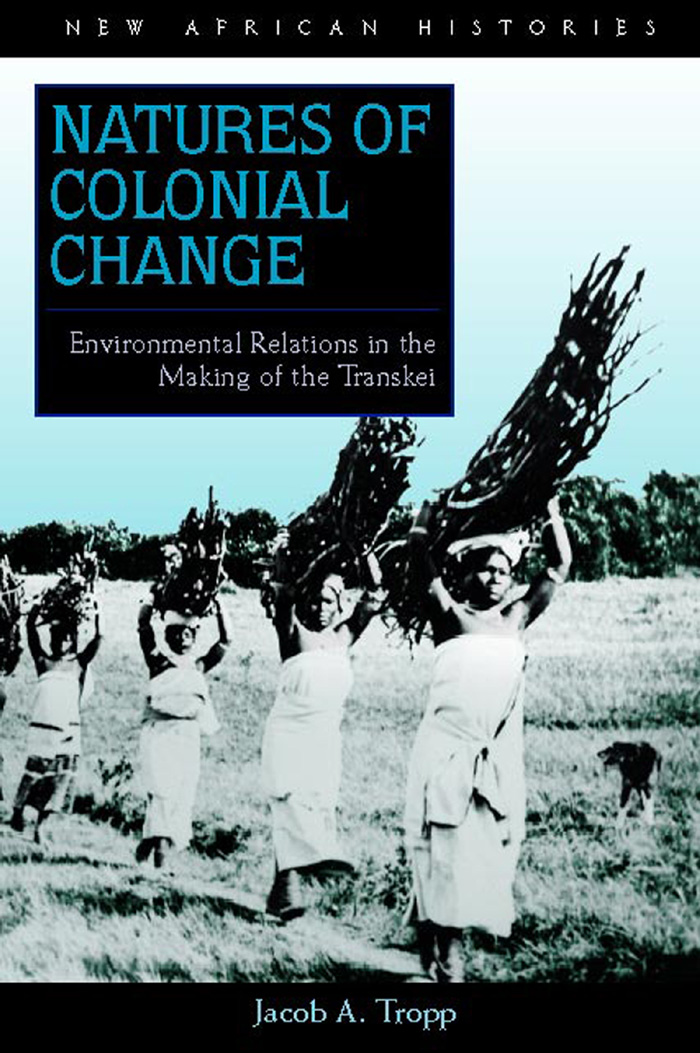

Jacob A. Tropp, Natures of Colonial Change: Environmental Relations in the Making of the Transkei

Ohio University Press

The Ridges, Building 19

Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohio.edu/oupress

2006 by Ohio University Press

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Cover: Photograph courtesy of Cape Town Archives Repository, Jeffreys Collection

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tropp, Jacob Abram.

Natures of colonial change : environmental relations in the making of the Transkei / Jacob A. Tropp.

p. cm. (New African histories series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1698-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8214-1698-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8214-1699-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8214-1699-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Indigenous peoplesEcologySouth AfricaTranskeiHistory. 2. Indigenous peoplesSouth AfricaTranskeiSocial conditions. 3. Forest ecologySouth AfricaTranskei. 4. Landscape changesSouth AfricaTranskei. 5. EuropeColoniesAfrica. 6. Transkei (South Africa)Colonization. 7. Transkei (South Africa)Environmental conditions. I. Title.

GF758.T76 2006

333.75'130968758dc22

2006021402

Acknowledgments

THERE ARE MANY WAYS to measure how much has gone into this books development, but Ill start with the personal. When I first visited South Africa and the Transkei in 1992a trip that really sparked my interest in pursuing historical research on the Eastern CapeI was also intensely curious about the long-term future of my relationship with my girlfriend at the time. Some thirteen years later, I find myself not only completing a book on the Transkei but very happily married to that former girlfriend, Elizabeth Herrmann, and together raising our four-year-old daughter, Rosa, and our infant son, Samuel. In the intervening years, there have also been significant lossesof family members, mentors, and friends. Among other things, these different experiences and the complex emotions they evoke have taught me important lessons which in turn have informed the writing of this present work: that memories and the unanticipated directions of life continually make the past novel, meaningful, and anything but simple.

I am deeply indebted to the many individuals and institutions that have contributed to this books development over the years. The University of Minnesota Graduate School, the MacArthur Program at the University of Minnesota, the Joint Committee on African Studies of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies (with funds provided by the Rockefeller Foundation), and Middlebury College together provided vital financial support for this project. While pursuing my doctorate at the University of Minnesota, many fellow students pushed my thinking in new directions both inside and outside of the classroom. I am particularly grateful for the opportunities to learn from and with Heidi Gengenbach, Amy Kaler, Premesh Lalu, Matt Martin, Marissa Moorman, Maanda Mulaudzi, Wapumuluka Mulwafu, Agnes Odinga, Derek Peterson, Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, and Guy Thompson. Various faculty members inspired and helped refine the early evolution of this project into a dissertation, and I would especially like to thank Jean Allman, the late Susan Geiger, Allen Isaacman, and Ben Pike for immersing me in the complexities and challenges of African Studies, and Jean OBrien-Kehoe for guiding me through the exploration of comparative themes in Native American history.

My research experiences in South Africa would not have been possible without the generosity, support, and warmth of many people. Lwandlekazi de Klerk, Veliswa Tshabalala, and Tandi Somana provided invaluable skills and insights as research assistants at different stages of my fieldwork. Staff at the South African government archives in Cape Town and the University of Transkeis Bureau of African Research and Documentation were particularly accommodating. Various individuals and families also graciously opened their homes and their social worlds to me in the Eastern Cape and in Cape Town, including Gerard Back, Tessa Dowling, Sue and Jim Gibson, Premesh and Vivienne Lalu, Hugh and Monica Macmillan, Mandla Matyumza, Maanda Mulaudzi and Amy Bell-Mulaudzi, Sophie Oldfield and David Maralack, Pule Phoofolo, and Lance van Sittert. And I am forever thankful to the various men and women in the Eastern Cape who so generously shared their time, their lives, and their thoughts with me in interviews and whose words have challenged and expanded my understanding of the Transkeis history.

I am also very grateful for the critical comments and constructive suggestions many colleagues have offered as I have presented parts of this evolving research at various annual meetings of the African Studies Association and the American Society for Environmental History, the 2003 International Conference on Forest and Environmental History of the British Empire and Commonwealth at the Centre for World Environmental History (University of Sussex), the Northeastern Workshop on Southern Africa (Burlington, Vermont), the History Department Seminar Series and the Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies at the University of the Western Cape, the Institute of Social and Economic Research at Rhodes University, and the History Departments Empires, Colonies, Nations Seminar Series at McGill University. Special thanks go to William Beinart, Ben Cousins, Derick Fay, Nancy Jacobs, Thembela Kepe, Premesh Lalu, Gregory Maddox, Jim McCann, Lungisile Ntsebeza, Lance van Sittert, Richard Tucker, and Andrew Wardell for their feedback, insights, and encouragement. I would also like to thank the editors of the International Journal of African Historical Studies at Boston Universitys African Studies Center for permitting me to reuse material from my previously published article The Python and the Crying Tree: Interpreting the Tales of Environmental and Colonial Power in the Transkei, IJAHS 36, no. 3 (2003): 51132.

Gill Berchowitz, Allen Isaacman, Jean Allman, and two anonymous reviewers for Ohio University Press offered crucial suggestions for revising the manuscript that have truly helped me transform my reading and writing of this material, several times over. Gill has been stellar throughout, patiently walking me through the production process and fielding my never-ending questions. I also want to thank the University of Fort Hare Library and Ronald Ingle for their assistance and permission to use photographs from the Piper Collection, the Cape Town Archives for permission to use photographs from the Jeffreys Collection, Conor Stinson at Middlebury College for producing the maps, and the production staff at Ohio University Press for all of their efforts. My gratitude and debts to Jean and Allen are many years deep and go well beyond the realization of this book. Thank you for your continuous confidence in my abilities (despite my own occasional doubts) and your enormous generosity and care as mentors, colleagues, and friends. Special thanks to Jean for helping me learn by example how teaching and scholarship can truly inform each other. And to Allen, who has most closely influenced this project from my fledgling ideas in a graduate seminar to its final throes as a manuscript, I send out my heartfelt appreciation of your frank, perceptive, and always constructive comments on my work; your caring guidance in my professional development; and your thoughtful understanding of and support during the highs and lows of my personal life.