Acknowledgments

We are indebted to a considerable number of people without whom this book would never have been written. It is not possible to thank them all without writing another book, but some names do stand out.

Over a decade before we lived in France, Professor Charles Taylor of McGill University taught both of us a method of thinking that allowed us to decode the French in record time, and that is very much at the origin of this book (though Charles Taylor has no doubt long forgotten both of us). Daniel Roux, Professor Thierry Leterre, Jean-Jacques Fraenkel, and Gustave (who we hope will recognize himself) shed invaluable light on the workings of the French mind and taught us many unexpected lessons. Miranda de Toulouse-Lautrec, David Hapgood, and Judson Gooding acted as sounding boards for our ideas many times over. Our agent Ed Knappman and our editor Hillel Black both went to bat for us and told us to be bold.

Finally, Peter Martin, director of the Institute of Current World Affairs, trusted us enough to pay our bills for two years in France and taught us to cultivate our first impressions. Lu Martin has been a constant source of support and encouragement to both of us.

To all weve named, and to the many friends and relatives who have given us inspiration, ideas, and support along the way, we would like to extend a big bear hug.

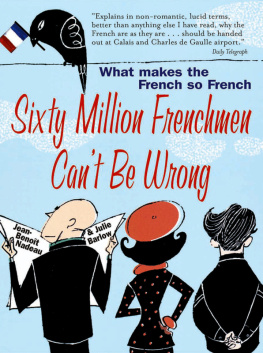

Introduction

Imagine a country where people work 35-hour weeks, take seven weeks of paid holidays per year, take an hour and a half for lunch, have the longest life expectancy in the world, and eat the richest food on the planet. A people who keep alive their local shopkeepers, who love nothing better than going to the public market on Sundays, and who finance the best health-care system in the world. A people whose companies are the least unionized and most productive among modern countries, and whose post-industrial consumer society ranks among the most prosperous in the world.

You are now in France.

Now imagine a country whose citizens have so little civic sense that it never crosses their minds to pick up after their dogs or give to charity. Where people expect the State to do everything because they pay so much in taxes. Where service is rude. Where the State is among the most centralized and pervasive in the world, and where the civil-servant class amounts to no less than a quarter of the working population. Where citizens tolerate no form of initiative or self-rule, where unions are so pervasive that they virtually dictate the course of government and even run French ministries.

You are still in France.

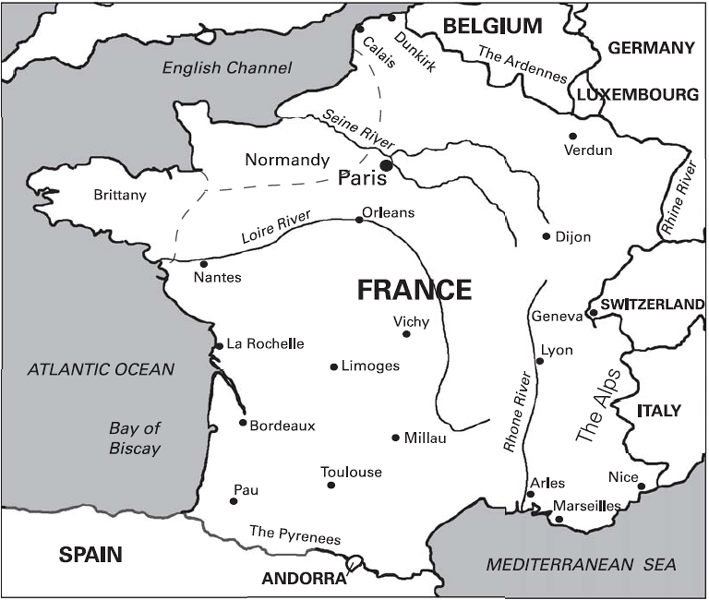

That was the riddle we faced when we arrived in Paris in January 1999, for a two-year stay. As we explored the country and reflected on our experiences there we would stumble upon even more mysteries. There was the famous French Paradox, of course. Dieticians have never understood how the French smoke, drink, and eat more fat than anyone in the world, yet live longer, and have almost no obesity and fewer heart problems than Americans. We saw it firsthand, and we didnt understand it either.

But we also saw another kind of French Paradox that was equally puzzling. In spite of high taxes, a bloated civil service, a huge national debt, an over-regulated economy, over-the-top red tape, double-digit unemployment, and low incentives for entrepreneurs, France at the turn of the third millennium had the worlds highest productivity index per hours worked, ranked as the number three exporter, was the worlds fourth-biggest economic power, and had become Europes powerhouse. How could this be? we wondered. France apparently wasnt meeting any of the criteria for growth according to the economic orthodoxy of the day. In case we forgot, influential publications like The Economist, The Wall Street Journal, and Fortune reminded us on a daily or weekly basis. The New York Times journalist Thomas Friedman published The Lexus and the Olive Tree, his bestseller on how globalization was changing the world (and how the world would have to change for globalization). His verdict on France was damning: If France was a stock, Id sell it, he wrote.

Among the many critical opinions of France, Thomas Friedmans held a special weight for us. In fact, among the many books we read on France written by American or British authors, his inspired us the most, or spurred us on, anyway. We had come to France as correspondents for the New Hampshire-based Institute of Current World Affairs. Jean-Benots project was to study why the French were resisting globalization. Julie was writing magazine articles on globalization-related topics. She interviewed the farmers who destroyed a McDonalds in southern France just before the World Trade Organizations ill-fated Seattle conference in December 1999. Then she talked to the director general of the World Trade Organization about the Seattle protests.

Globalization was certainly on everyones minds when we arrived in France. But it wasnt the only issue the French were grappling with. It didnt take us long to see that France was a society in flux. The European Union had rolled in the euro eight days before we arrived, and the days of the franc were numbered. Socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin was privatizing government-owned French companies at a rate greater than Britain in the 1980s. Judges were beginning to launch serious investigations into embezzlement scandals, corruption, and influence-trafficking among politicians. Frances political class was reeling. It was not the same country we had visited as tourists seven years earlier.

It also didnt take us long to see that Thomas Friedman was wrong; his predictions hadnt come true, anyway. Frances economy was doing quite well. On a hunch, we shifted the globalization idea to the backs of our minds and decided to just explore France and French thinking.

Thousands of elating and frustrating experiences reinforced or contradicted our ideas about the French over our first six months. We werent just studying France; we were trying to make a life for ourselves. Anyone who has ever moved away from their own country knows about the unforeseeable problems that pop up every day, thwarting your effort to get comfortable in a foreign land. We decided to look at these problems as learning experiences, and they were. The process of opening a bank account, finding and furnishing an apartment, and making friends taught us many unexpected lessons.

After several months in France, it was pretty clear to us that the French were not really resisting globalization. Like just about everyone else on the planet, they were speculating about how la mondialisation would change their country. French companies, meanwhile, were proving to be serious players in the globalizing marketplace. Aerospace giant Airbus was already giving Boeing a beating. French car manufacturer Renault was taking control of Nissan. The French food distributor Carrefour had risen to number two after Wal-Mart.

So much for Jean-Benots fellowship topic.

Many things Thomas Friedman said about France in The Lexus and the Olive Tree were true. Yet we had the impression we were observing two countries in one. France was both rigidly authoritarian and incredibly inventive. It was a country that had barely any clout left on the international stage, but was still incredibly influential a country at once traditional, if not archaic, and modern to the extreme. Clippings piled up in our filing cabinets, and notes accumulated in our journals. We had a paradoxical picture of France.