Planters and the Making of a New South

1979 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN 0-8078-1315-X

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78-25952

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Billings, Dwight B 1948

Planters and the making of a new South.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. North CarolinaIndustriesHistory. 2. North CarolinaEconomic conditions. 3. North CarolinaSocial conditions. I. Title.

HC107.N8B5 330.975604 78-25952

ISBN 0-8078-1315-X

To the working people

of Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina,

and Sterns, Kentucky,

where southern labor stirs.

Contents

Tables

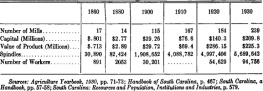

3.1 Regional Manufacture of Agricultural Implements...

3.2 Percentage of Average Wage Earners, 1879, and of Employees, 1947, in Selected Manufacturing Industries Employed in the South...

4.1 Economic Indicators for North Carolina and the South, 1880...

5.1 North Carolina Farm Ownership in 1900...

5.2 Control of Tenants in North Carolina in 1900...

5.3 Concentration within North Carolinas Landholding Elite in 1900...

8.1 North Carolina Populist Gubernatorial Vote, 1896, by Selected County Characteristics...

8.2 Occupational Composition of the North Carolina Senate, 1897...

8.3 Religious Composition of the North Carolina Senate, 1897...

8.4 Educational Composition of the North Carolina Senate, 1897...

8.5 Comparison of 1897 Senate Voting Clusters by Average County Background of Populist Senators...

8.6 Class Structure in Rural North Carolina...

9.1 Occupational Composition of the Democrats in the 1899 Senate ...

10.1 Comparison of Estimated Long-Run Price Elasticities for Cotton Growing (18831914) and Total Value Added by Manufacturing Per Capita (1890 and 1900), for Ten Southern States...

Figures

3.1 Regional Income Shares, 18401950...

4.1 Aggregate Real and Personal Wealth Per Capita (Free), 1860...

7.1 Turnover in North Carolina Senate...

7.2 Total State Disbursements (in millions)...

8.1 Two-Dimensional Representation of the Fusion Senate, 1895...

8.2 Two-Dimensional Representation of the Fusion Senate, 1897...

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my appreciation to the many people who supported me in the preparation of this book. Gerhard Lenski, at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, gave personal encouragement and made numerous suggestions that have contributed much to the final product. Lester Salamon gave valuable comments, and his analysis of Mississippi as a developing society provided a chief exemplar for my research. Had I not discovered Salamons work, my own would have had far less coherence. Robert Gallman, John Reed, and Everett Wilson, all at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, were most helpful.

I want to thank my family for their years of love and encouragement and also many friends and colleagues whose human support and intellectual contributions during this writing have been invaluable. These include Brian Anderson, Doug Arnett, Lars Bjorn, Larry Busch, Dan Chirot, Ron Eller, Robert Goldman, Jack Hoadley, Floyd Hunter, Al Imershein, Charles Ragin, Gregg Sampson, Rachael Tayar, and Dave Walls. Three of these deserve special mention. Dan Chirot introduced me to historical sociology and political economy. Bob Goldman and Rachael Tayar were constant sources of ideas and support. I also wish to thank the staffs of the North Carolina Collection and the Southern Historical Collection of the Louis Round Wilson Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, as well as the Danforth Fellowship program. Finally, Marlene Pettit did a cheerful and skilled job typing the manuscript.

Planters and the Making of a New South

1. Introduction

The history of the American South provides many challenges to the sociologist studying social classes and social change. Although the regions commercial agriculture developed as part of the modern world market system, slavery is reputed to have produced a society in the South whose aristocratic tendencies and economic interests were at odds with the rest of American society. Slaveholding conflicted with the dynamic, expansionist, middle-class capitalism of the North. The political expression of this conflict was the Civil War, a bloody fight to determine which pattern of social relations would be dominant on the American continent.

Historians have been fascinated by the effects of the war on southern society. C. Vann Woodward in Origins of the New South is an example of one who claims that no other class in our history fell so rapidly or so completely as the Souths planter aristocracy after the Civil War. A number of French aristocrats who never lived to see the nineteenth century or Russian aristocrats who did not see much of the twentieth century might argue the point were they here to do so. Nevertheless, apart from its accuracy, which I shall discuss later, this prevalent view dramatizes the extent of social change in the South: a rich agricultural South based on the labor of African slaves; a wartorn South first conquered by northern troops and then by northern railroads; and, finally, a New South, rich in industry and poor in wages.

This drama creates fascinating problems for sociologists interested in the process of stratification; they could correlate the rise and fall of social classes with the confusing patterns of southern politics. The Souths uneven development poses important problems for students of political and economic development. Why have some formerly backward areas of the South, such as the Carolina Piedmont, industrialized and others, such as the Delta region, seem never to change? I shall try to make sense of the patterns of social stratification and social change in the South by analyzing the economic and political development in the state of North Carolina after the Civil War.

In 1860, North Carolina was the poorest southern state. Compared with the grandeur of its neighbors, Virginia and South Carolina, North Carolina appeared humble. Its eastern counties supported a patrician class of slaveholders who dominated the state politically, but its vast western territories housed a huge population of yeomen and subsistence farmers whose life styles, in comparison, must have seemed frontierlike. Despite its comparative backwardness, however, by 1900, North Carolina was becoming the industrial leader of the New South. If we could return to the North Carolina of 1880, at the midpoint of this transition, it would not be clear at all how such a remarkable transformation could be possible.

In 1880 the effects of Civil War were still highly visible in North Carolina. The last of the federal troops had been withdrawn from the South only three years earlier. Roughly forty thousand North Carolinians (the greatest number in any Southern state) died in a war many had opposed. Approximately 350,000 slaves had been emancipated, but proprietary control was restored with the development of the sharecropping system. Much of the land was still in ruins. Because slaves and land had been the Souths capital, there was little money for rebuilding. The ruinous costs of war were further compounded by chronic agricultural depression. There were more white than black sharecroppers because yeomen fell increasingly into debt and were forced into the tenancy system. By 1880 one-third of the states farms were operated by tenants.