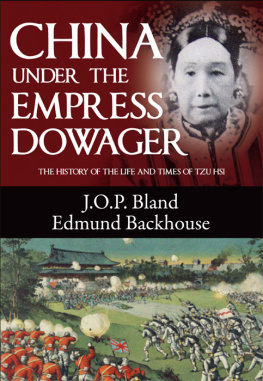

The Power Game in Byzantium

Antonina and the Empress Theodora

James Allan Evans

Continuum International Publishing Group

The Tower Building 11 York Road London SE1 7NX | 80 Maiden Lane Suite 704 New York NY 10038 |

www.continuumbooks.com

James Allan Evans 2011

Photographs Jonathan Bardill

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

James Allan Evans has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4411-7252-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

For Eleanor

List of Illustrations

Page 2. Great Palace, Constantinople.

Page 8. Mosaic from the Great Palace, Constantinople, showing a wild beast hunt.

Page 10. Constantinople in the Justinianic Period.

Page 51: Mosaic of Justinian from S. Vitale, Ravenna. Mosaic of Theodora from S. Vitale, Ravenna.

Page 53. Church of Hagia Sophia.

Page 74. Church of Hagia Eirene.

Page 94: Map. The Empire of Justinian, 550 CE.

Page 106. Interior, SS. Sergius and Bacchus church.

Preface

Why in the world do we need another book on the empress Theodora? A querulous portion of the reading public will ask that question and some reviewers as well and reasonably enough. The simple answer is that we dont, though if only books that were necessary were written, library stacks would be half empty. Authors write books on well-worn subjects either because they imagine that they can shift the focus, and present a familiar picture with new background lighting, or because they are self-important enough to think that somewhere, there exist readers for their publication. Often both motives are at work. In my defence, however, I would argue that this is not simply a book about Theodora, or even about the imperial couple, like Robert Brownings superb Justinian and Theodora , which combines an unparalleled grasp of history with a splendid literary style. It is about two women who knew how to use political power to advance their interests, lead lives outside contemporary social norms and influence the workings of the government. They lived in a period when most women lived lives circumscribed by social convention, and their example shows that women even if they were born into the lowest ranks of society could play the power game as well as men. They were also outsiders in a new age of intolerance.

Labelling the reigns of Justin I and Justinian a new age of intolerance is a harsh judgement, but it can be justified. The Late Roman Empire had evolved into the Christian state of Romania, Yet, from 482 until the accession of the old soldier, Justin I, Justinians adoptive father, the religious policy of the eastern Roman Empire was regulated by the Henotikon , a Unity Creed formulated in the emperor Zenos reign by the patriarch of Constantinople, Acacius, and his strategy for dealing with the bitter quarrel about the nature of the Trinity was to anoint it with the healing oil of imprecision. The Henotikon , which Acacius crafted, was a masterpiece of artful vagueness, with the result that it satisfied no one, which was an impossible goal anyway, but it did allow the peaceful co-existence of those Christians who believed in the Chalcedonian Creed and those who could not stomach it. It represented official willingness to separate church and state just far enough to allow freedom to choose. Yet it was a compromise; and for Rome, and the Latin bishoprics of what was once the western Roman Empire, there could be no compromise with ultimate truth, which only Rome had the mandate to pronounce.

The Henotikon would not do. In 484, the pope in Rome excommunicated Acacius, thus beginning the Acacian Schism, which lasted until the emperor Anastasius died and his successor, Justin I, egged on by his wife, a convinced Chalcedonian like himself, surrendered to Romes demands. Pope Hormisdas in Rome insisted that opposition to the decision of Chalcedon must be suppressed. The view of old Anastasius, who was no Chalcedonian himself, had been that it was not worth spilling blood to enforce what Rome considered orthodoxy. Justin and his nephew Justinian thought otherwise.

This was the Indian summer of the classical world, when the Greek classics were still the foundation of a cultivated mans education. Constantinople, founded by Constantine in 324, was the new Rome, and the language of law was still Latin, but the language of communication and culture was Greek. The Byzantines saw themselves as citizens of Romania, and though they might speak Greek, they called themselves Romans, not Graikoi , which had connotations of spinelessness. Nor did they call themselves Hellenes, for Hellene now meant pagan. Hellenism was a culture that endangered the Christian soul.

Yet paganism was by no means dead, though it was outlawed, and sacrifices had been forbidden for two centuries. An anti-pagan pogrom in Constantinople in 5456 swept up a great number of the citys educated elite, who were assembled in churches to be taught the truth of Christianity, Paganism had become a bootleg religion, surviving underground among the educated upper crust as nostalgia for the intellectual traditions of the past and, on the popular level, as sorcery and superstition and inherited awe for the ancient holy sites where the gods of Greece and Rome were once worshipped. Neoplatonic philosophy was still taught in the schools of Alexandria and Athens and, in Athens at least, where Justinian terminated the school, it made no compromise with Christian thought. Classical culture that was the mark of an educated person had been purely pagan and historians of the Late Empire, who wrote their histories in self-conscious classical Greek and took Herodotus and Thucydides as their models, seem like dual citizens, acknowledging their allegiance to the pagan past almost as much as to the Christian present-day world. Paganism still had room to breathe under Anastasius. In his reign, the pagan apologist Zosimus could still produce a history of Rome that drew a connection between Romes decline and its adoption of Christianity. Freedom to express publicly views like that disappeared when Justinians uncle, Justin, appropriated the imperial throne and, once Justinian himself became emperor, he re-enacted the old laws outlawing paganism and initiated his first pagan witch-hunt. More of them would follow.

The intolerance extended to the anti-Chalcedonians. Monophysite, the label generally applied to them, came into popular usage as a pejorative term only in the eighth century, long after Justinian was dead, though the Monophysites themselves were already using its antonym diphysite or diaphysite for their rivals. But Monophysite has become an umbrella term for all Christians who believe that Christs humanity was subsumed by his divine nature, and I shall go along with the same convenient anachronism. Monophysite in this book means simply anti-Chalcedonian. In the reign of Anastasius, who was a Monophysite himself, it would have been inappropriate to call Monophysitism a heresy. Whatever the Church of Rome thought, in the eastern provinces, most Christians but not all considered Monophysitism the correct faith and for them Justinians wife, the Monophysite empress Theodora, would be the believing queen, defender of true orthodoxy. Yet, once Justin I took hold of the imperial throne and a new regime began, Monophysitism became officially a heresy that was to be suppressed by force if necessary. A line was drawn in the sand if we may make an analogy between theological controversy and sand. Chalcedonian Catholicism became the authorized religion, the imperial faith of Romania, and Monophysitism became the other. In the east, the Chalcedonians were labelled melkites, the emperors men melkite was derived from the Syriac word for king, in Greek, basileus . It would be Melkite churchmen who coined the label Monophysite for the anti-Chalcedonians. The Monophysites were not disloyal to the emperor, nor to the idea of the Roman Empire, but there were limits to their loyalty. With a helping hand from the empress Theodora they would develop into a separate denomination with its own priests and bishops and, whether or not its founders intended it, Monophysitism became a separatist movement.