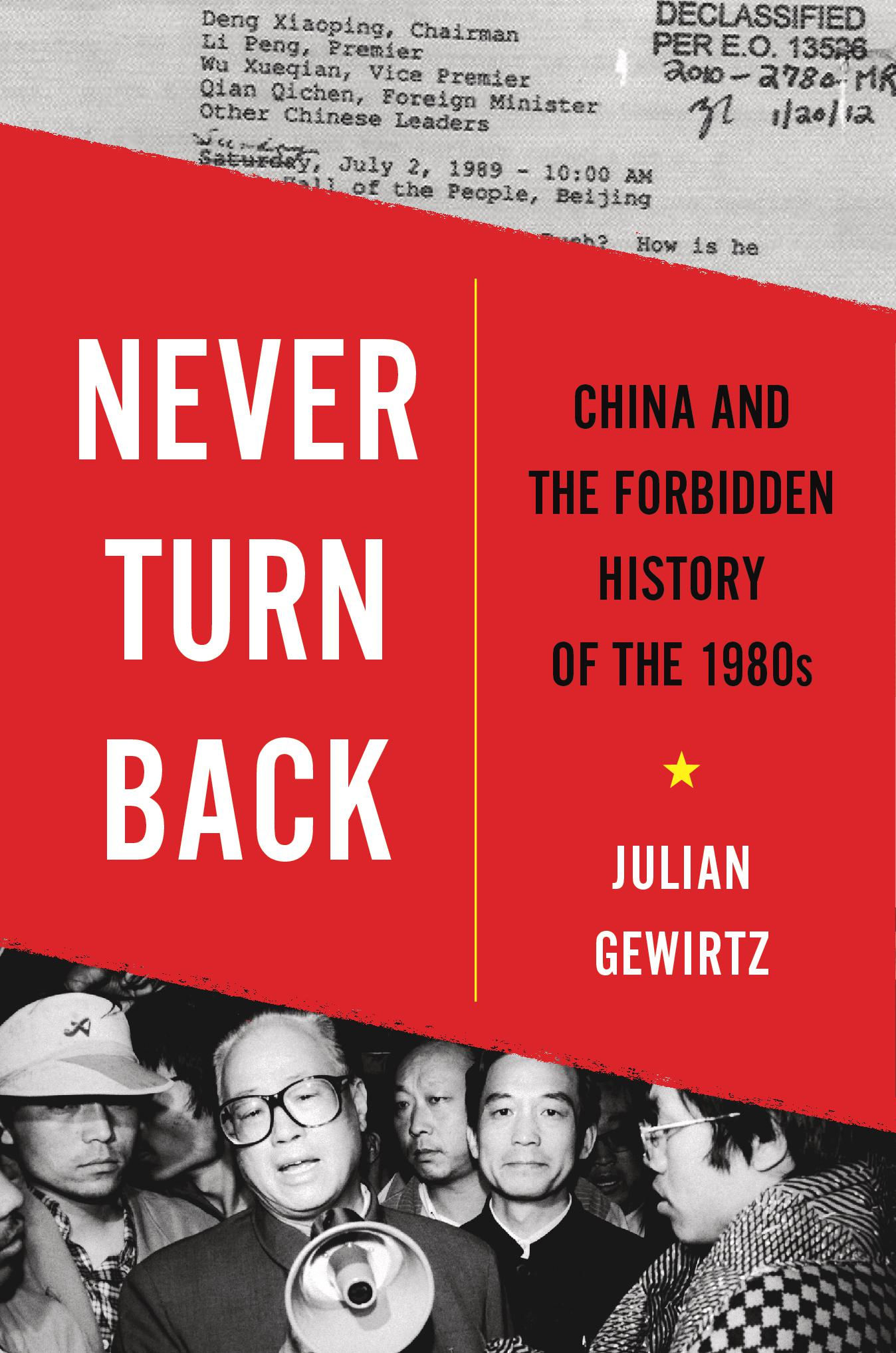

NEVER TURN BACK

CHINA AND THE FORBIDDEN HISTORY OF THE 1980

JULIAN GEWIRTZ

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts|London, England

2022

Copyright 2022 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

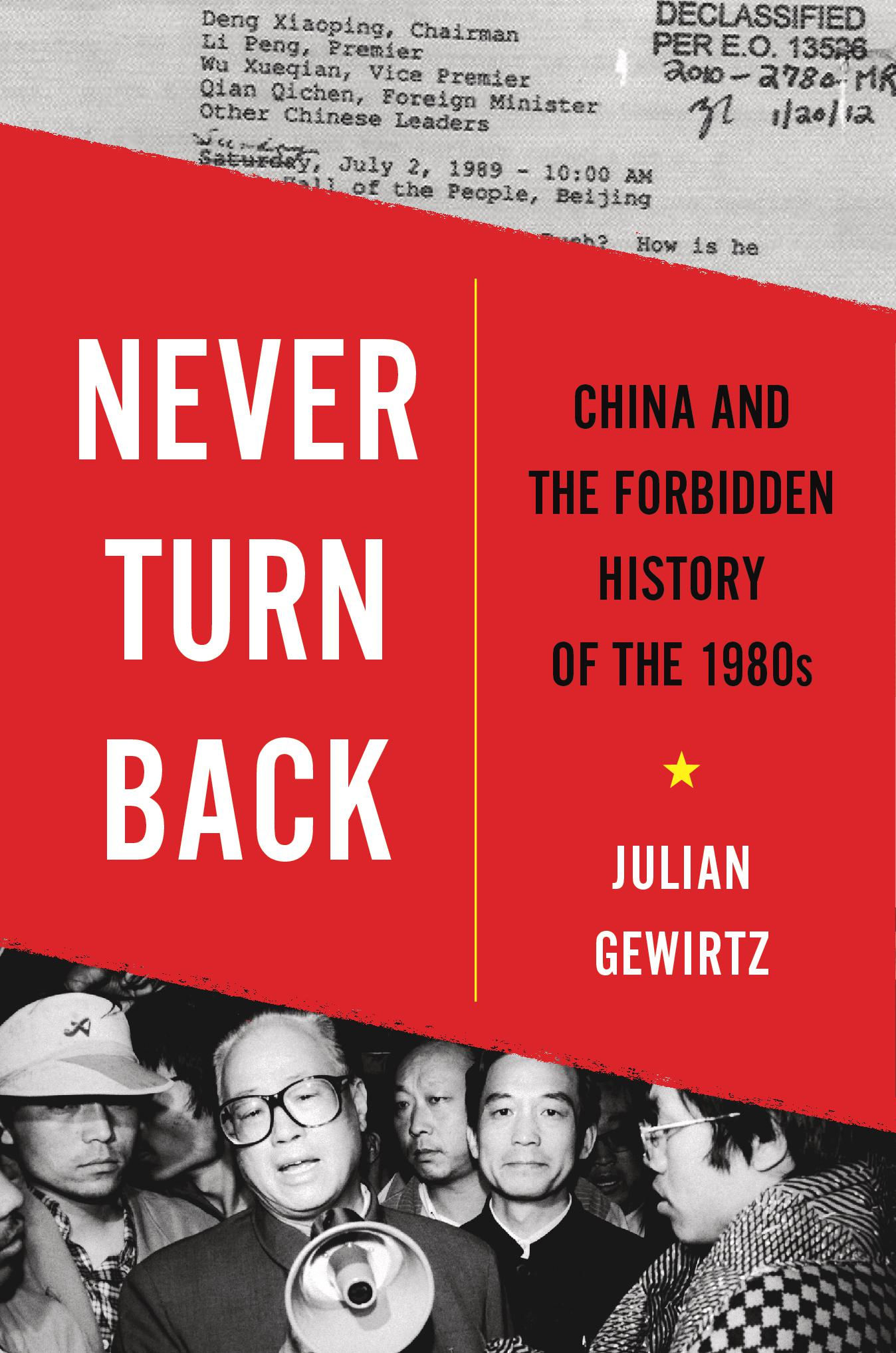

Jacket design: Brianna Harden

Jacket photograph (bottom): Chip Hires | Getty Images/AFP

978-0-674-24184-8 (cloth)

978-0-674-28738-9 (EPUB)

978-0-674-28737-2 (PDF)

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Gewirtz, Julian B., 1989 author.

Title: Never turn back : China and the forbidden history of the 1980s / Julian Gewirtz.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022001879

Subjects: LCSH: HistoriographyChina20th century. | Political cultureChina. | ChinaPolitics and government19762002. | ChinaHistory19762002. | ChinaHistoryTiananmen Square Incident, 1989. | ChinaEconomic policy19762000.

Classification: LCC DS779.26 .G49 2022 | DDC 951.05/8dc23/eng/20220427

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001879

CONTENTS

On January 18, 2005, tucked away on page four of the official Peoples Daily, just below an article on post-tsunami inspections and above a weather report, a three-line notice reported the death of an eighty-five-year-old man: Comrade Zhao Ziyang suffered from long-term diseases of the respiratory system and the cardiovascular system and had been hospitalized multiple times, and following the recent deterioration of his condition, he was unable to be rescued and died on January 17 in Beijing at the age of 85.

A casual reader of the newspaper would certainly be forgiven for not noticing the item. The obituary was notable mainly for its brevity and omissions: it did not mention that Zhao had held Chinas top two leadership posts as premier of the State Council and then as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Nor did it acknowledge that he had made any contributions to Chinas reform and opening, the agenda of economic development and openness to the world China pursued soon after the death of Mao Zedong. Reform and opening remained as a centerpiece of official policy, mentioned nearly a dozen times in that days newspaper, but Zhaos central role in shaping it had already been systematically erased from official accounts of the history of this period. Indeed, well before Zhaos death, the CCP had rewritten the entire history of Chinas 1980sa tumultuous, transformational decadeand subjected it to far-reaching distortion, even though it was one of the most consequential periods in the countrys history.

In popular accounts around the worldas well as in the official narrative told by Chinas rulersthe 1980s in China are typically treated as a time of linear change, moving smoothly from Deng Xiaopings rise to power in 1978 and the leap into reform and opening to new heights of wealth and modernization. In this telling, the decade whizzes by; the crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen protests is at most a harsh interruption before the linear narrative begins again in 1992 with Deng pushing for faster reform on his Southern Tour.

This story is a myth. It exists in large part because the CCP has suppressed sources and created a powerful and widely repeated official narrative about China in the 1980s that erases key figures, blots out policies and debates, covers up acts of violence, and forbids public discussion of alternative paths. In contrast to that narrative, the 1980s in China were a period of extraordinary open-ended debate, contestation, and imagination. Chinese elites argued fiercely about the future, and official ideology, economic policy, technological transformation, and political reforms all expanded in bold new directions.

These years of tumult, searching, and struggle transformed China, but by the time protesters filled Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989, the leadership had not reached agreement on how China ought to modernize. Following the crackdownwhich included both the massacre of civilians and the purge of top officialsa new consensus emerged, and Chinas remaining leaders offered a newly consolidated vision of the Chinese system as well as a refashioning of the events of the 1980s designed to serve this post-Tiananmen agenda. Among many other changes, they built up the cult of Deng Xiaoping while erasing Zhao Ziyang and fellow top leader Hu Yaobang, reinterpreted the pursuit of rapid economic growth, and argued for the absolute necessity of fusing the party and the state. They abandoned or left unfinished many of the political reforms pursued during the 1980s. Before even replacing the tank-scarred stones of Tiananmen Square, they had pushed out their new narrative and staked the partys fortunes on it.

What is today called the China modelextraordinarily rapid economic growth paired with enduring authoritarian political controlwas not the only vision of the future Chinas leaders pursued in the decades following Mao Zedongs death in 1976. They imagined and experimented with many possible China models in the 1980s. Yet Chinas rulers have worked hard to conceal this fuller story and the pivotal choices that determined Chinas development. Bringing this forbidden history back into focus is vital. One of the most momentous transformations of the twentieth century has been the subject of immense historical distortion to bolster the legitimacy of the Communist Partys chosen path.

The fundamental question of the 1980s was one that had motivated Chinese officials and intellectuals for a century: how can China become modern? Deng Xiaoping declared in January 1980 that modernization was the essential condition for solving both our domestic and our external problems, and the 1980s would be a decade of great importanceindeed, a crucial decadeto Chinas development.

For Chinese officials and intellectuals, the challenge was to find a Chinese path to modernization that did not copy or import wholesale a foreign conception of modernity. To be sure, some thinkers embraced the West with few reservations, praising Americanization and Westernization. But those views were unusual. The more important predicament was how to define modernization anew in Chinadrawing on ideas and innovations from around the world but on Chinese terms.

To Deng Xiaoping, economic development was the essential element of modernization, and to achieve this goal, he was willing to permit markets to multiply and international trade to expand. But becoming richer on its own was not enough. Deng and other senior officials devoted significant attention to other domains that constituted Chinas modernization, including official ideology, advanced technology for both economic and military purposes, and the political system. They projected confidence, despite daunting challenges. On a hike up Luosanmei hill in Guangdong Province in January 1984, Deng Xiaoping was warned that the path ahead was steep and treacherousand in a moment made for propaganda, Deng replied sportingly, Never turn back. The line soon was widely publicized as a mantra for the leaderships resolve to forge ahead with reforms no matter the difficulty, though it belied the fierce contestation raging over Chinas future.

The Chinese leadership in the 1970s had embraced a set of objectives, proposed by Zhou Enlai, known as the Four Modernizationsdeveloping modern agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology (S&T). However, the Four Modernizations were only one piece of a much larger agenda.

Next page