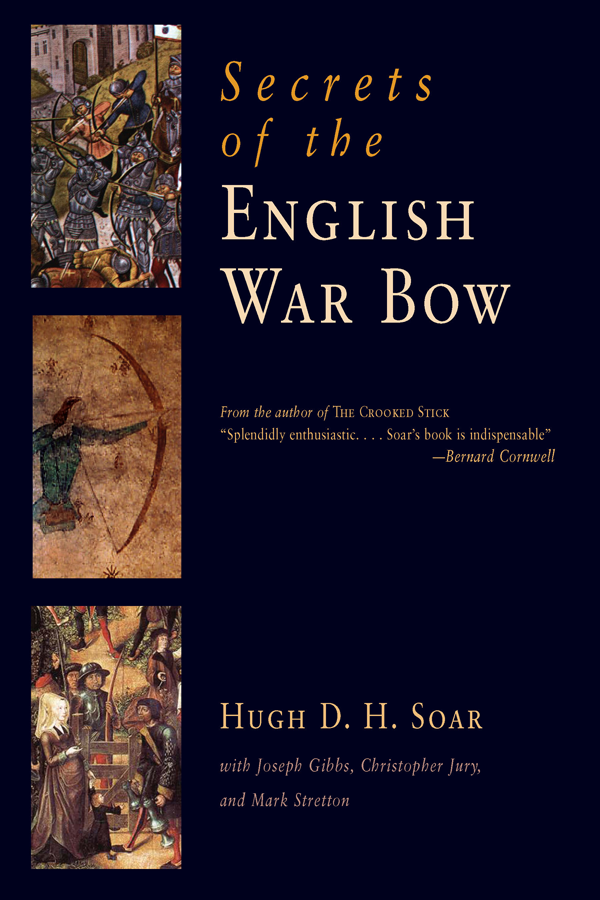

Copyright 2006 Hugh D. H. Soar except the following:

Chapters and accompanying illustrations copyright 2006 Mark Stretton

Illustrations credited to Joseph Gibbs copyright 2006 Joseph Gibbs

Illustrations credited to Christopher Jury copyright 2006 Christopher Jury

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

Preface

Our English archers shot their shafts,

As thick as hayle in skye,

Ad many a foeman on the feelde,

That happy day did dye

A ballad of Agincourt, 1415 (anon.)

In The Crooked Stick: A History of the Longbow, a companion volume to this book, the slowly unfolding story of the weapon appearedits development was traced from a Stone Age origin lost in time, through prehistory and early recorded history, first as the hunting weapon that gave humans mastery of their environment, then as a successful tool in warfare, and more recently to its use as an instrument for pleasure and recreation. With this knowledge at our backs, in this new book we will examine both in text and photographic detail the ins and outs of this most effective and charismatic of war weapons, its creation, and that of its companion arrow and its string.

From a master arrowsmith come some fascinating details of how replica arrowheads are hand forged today and of their awesome penetrative power when shot from a heavy draw-weight bow at both static and moving targets.

From a modern maker of war bows are illustrations of his processes as he crafts a yew bow, and through the skills of a master fletcher we are shown, by photograph and text, the skilful creation of a medieval arrow from a beginning as an unshaped stave of wood to a fully fletched conclusion.

To complement the work of these craftsmen, we will look at the English bowman who used and trained with thesepotent weapons andin his heydaythe tactical use to which his military commanders put him. Of the many battles that drew upon his courage and tenacity of purpose we will examine four from the French wars, and from their outcome we may judge both the skills and the shortcomings of charismatic leaders.

Irrelevant to battle it has become, but the longbow retains a hold on the minds of Englishmen and others, quite disproportionate to the simplicity of its purpose. Those who kept faith with the war bow turned to it later for recreation and pleasure, and it is proper that we should look closely and carefully at its use, easing from it and its associated arrow those secrets so familiar to our bowman forebears.

Read on and enjoy.

Chapter One

THE ENGLISH WAR BOW

The might of England standyth upon her archers

Sir John Fortescue (d. 1478)

There can have been no more awesome sight for those who sought to challenge the might of England upon the battlefield than to be faced by rank upon rank of stolid longbowmen. Cold-eyed professional fighters, arrogant and xenophobic to a man, they stood in silence, confident of their ability, deadly shafts notched on taut bowstrings, anticipating the sound of battle horn and drum, ready to loose their fearsome arrow storm to maim and kill all in its path, for the arrow is blind and no respecter of degree: lowly foot-slogging peasant or high-born man-at-arms, neither escaped its murderous point.

It was the task of these bowmen to dull the opposition. Disciplined at village butt on holy days to shoot strongly and to effect, they knew their worth, these free-born Englishmen and their Welsh companions, and they did their work well.

Of the many battles in which the longbow and those who used it were prominent, none has been so thoroughly described as Agincourtfought on a late October day in 1415a day dedicated to saints Crispin and Crispinian. While the lowly bowmen are given credithow could it be otherwiseunderstandably,perhaps, official English accounts, of which there are many, emphasize the activities of the men-at-arms.

Then the French came pricking down as if to over-ride our men, but God and our archers made them stumble. Our archers shot no arrows off target; all caused death and brought to the ground both men and horses. For they were shooting that day for a wager. Our stakes made them fall over, each on top of the other so that they lay in heaps two spears length in height. Our king with his company and men at arms always fought on for he battled with his own hands. When the archers ran out of arrows they laid on with stakes.

Another source states:

The warlike bands of archers with their strong and numerous volleys darkened the air, shedding as a cloud laden with a shower, an intolerable multitude of piercing arrows, and inflicting wounds on the horses, either caused the French horsemen [who were intent upon overriding them and fighting the English from the rear] to fall to the ground, or forced them to retreat, and so defeated their dreadful purpose.

With archery thus dismissed, the author reserves the more purple of his prose for a gory description of the battlefield.

O, deadly war, dreadful slaughter, mortal disaster, hunger for death, insatiable thirst for blood, insane attack, impetuous frenzy, violent insanity, cruel conflict, merciless vengeance, immense clash of lances, prating [aimlessness] of arrows, clashing of axes, brandishing of swords, breaking of arms, infliction of wounds, letting of blood, bringing on of death, hacking up of bodies, killing of nobles! The air thunders with dreadful crashes, clouds rain missiles, the earth absorbs blood, breath flies from bodies, half dead bodies roll in their own blood, the surface of the earth is covered with the corpses of the dead, this man

While English accounts of Agincourt adequately describe the ebb and flow of the days events, it is to the French accounts that we turn for graphic illustration, in particular, the dress and explicit activity of the archers. Most of these men, we are told, were without armor, dressed in their doublets, their hose loose around their knees, having axes or swords and hatchets hanging from their belts. Many had bare heads and were without headgear although some had hunettes or cappelines of boiled leather and some of osier on which were bands of iron. It was also noted that some archers went barefoot.