MONGOLIAN NOMADIC SOCIETYNORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES

Recent Monographs

67. I SLAM AND P OLITICS IN A FGHANISTAN

Asta Olesen

68. E XEMPLARY C ENTRE , A DMINISTRATIVE P ERIPHERY

Hans Antlv

69. F ISHING V ILLAGES IN T OKUGAWA J APAN

Arne Kalland

70. T HE H ONG M ERCHANTS OF C ANTON

Weng Eang Cheong

71. A SIAN E NTREPRENEURIAL M INORITIES

Christine Dobbin

72. O RGANISING W OMENS P ROTEST

Eldrid Mageli

73. T HE O RAL T RADITION OF Y ANGZHOU S TORYTELLING

Vibeke Brdahl

74. A CCEPTING P OPULATION C ONTROL

Cecilia Nathansen Milwertz

75. M ANAGING M ARITAL D ISPUTES IN M ALAYSIA

Sharifah Zaleha Syed Hassan and Sven Cederroth

76. S UBUD AND THE J AVANESE M YSTICAL T RADITION

Antoon Geels

77. F OLK T ALES FROM K AMMU VI: A S TORY -T ELLERS L AST T ALES

Kristina Lindell, Jan-jvind Swahn and Damrong Tayanin

78. K INSHIP , H ONOUR AND M ONEY IN R URAL P AKISTAN

Alain Lefebvre

79. T HAILAND AND THE S OUTHEAST A SIAN N ETWORKS OF THE V IETNAMESE R EVOLUTION , 18851954

Christopher E. Goscha

80. I NDIAN A RT W ORLDS IN C ONTENTION

Helle Bundgaard

81. C ONSTRUCTING THE C OLONIAL E NCOUNTER

Niels Brimnes

82. R ELIGIOUS V IOLENCE IN C ONTEMPORARY J APAN

Ian Reader

83. M ONGOLIAN N OMADIC S OCIETY

Bat-Ochir Bold

84. I NDIGENOUS P EOPLES AND E THNIC M INORITIES OF P AKISTAN

Shaheen Sardar Ali and Javaid Rehman

85. L EE K UAN Y EW : T HE B ELIEFS B EHIND THE M AN

Michael D. Barr

MONGOLIAN NOMADIC SOCIETY

A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE MEDIEVAL HISTORY OF MONGOLIA

Bat-Ochir Bold

CURZON

Nordic Institute of Asian Studies

Monograph Series, No. 83

First published in 2001

by Curzon Press

Richmond, Surrey

Bat-Ochir Bold 2001

All illustrations and maps are copyright of the author and may not be reproduced without his express permission.

British Library Catalogue in Publication Data

Bold, Bat-Ochir

Mongolian nomadic society : a reconstruction of the medieval history of Mongolia. - (NIAS monographs ; no. 83)

1.Nomads - Mongolia - History 2.Mongolia - History

I.Title

951.7

ISBN 0-7007-1158-9

To my parents

Prof. L. Bat-Ochir and Kh. Cendjav

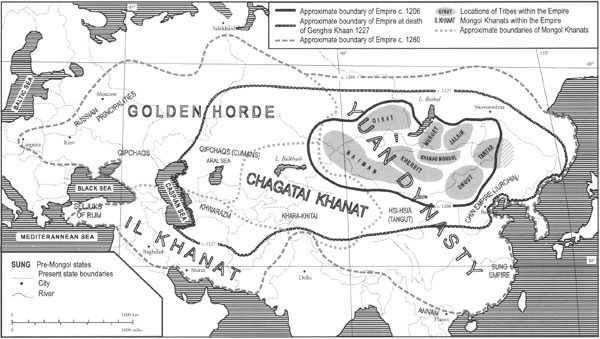

M APS

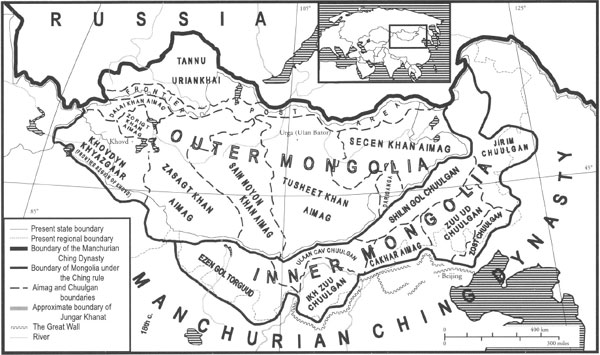

1 The Mongol empire in the 13th century

2 Mongolia about 1800

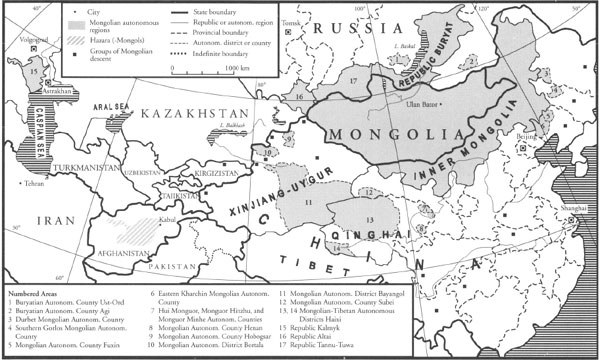

3 The Mongols in Asia today

F IGURES

T ABLES

This work is the result of many years of research which I began while studying the philosophy of history at the University of Ulaanbaatar. I was able to continue this research as a DAAD grant awardee at the Humboldt University in Berlin from 1990, and complete it within the framework of post-doctoral studies via the HEP (Hochschule-rneuerungsprogramm University Renewal Programme) at the Free University in Berlin. Throughout these years I learnt a good deal in my professional life. In particular, the fall of the Berlin Wall in the transition period 198990, the consequent collapse of socialism, and the radical change in its ideologised way of thinking opened up new perspectives for me personally. When, as an eyewitness from the faraway country of the nomads, I experienced how people knocked the Berlin Wall down with all their strength and resources, I was convinced that the same could be done in the future to Mongolian historiography, which has been petrified and cemented by decades of communist ideology.

I would like to take this opportunity to express my thanks to my German friends and colleagues for their immeasurable help and encouragement in my research work in general, and for their guidance and cooperation. I would also like to thank my colleagues at NIAS for their encouragement in the continuation of my research in Scandinavia, especially Leena Hskuldsson and Gerald Jackson for their friendly and professional help in this works publication. I thank also my friend John Duggan for his help with preparation of this work in English. And finally, my heartfelt thanks go to my wife for without her unique support and tolerance this work would never have been completed.

Bat-Ochir Bold

Reykjavik 2000

There is no satisfactory solution to the problem of transliteration when one is dealing with words from many languages and scripts. In this work I attempt to transliterate Mongolian, Tibetan, Manchurian, Chinese and Arabic words, names and titles according to the popular transliteration system of the respective languages. I have preferred to transcribe most Mongolian terms in accordance with modern Mongolian. But for some well-known Mongolian names (e.g. Genghis Khaan) I have used the spelling conventionally followed by European Orientalists today. Chinese names and terms are transcribed using the pinyin transliteration system. Terms appearing in citations and in book titles, however, are preserved as they appear in the original work. For this reason some terms may appear in various transliteration forms.

Until the collapse of the socialist system in Mongolia in 1990 and the consequent decline of the Soviet Unions influence upon all areas of Mongolian society, Mongolian social sciences had been fundamentally schematised in accordance with the prevailing political ideology of socialism. This situation was especially characteristic of the theoretical treatment of Mongolian historiography after the 1930s. Mongolian historians as well as Russian specialists in Mongolian studies, and historians who conducted historical research on Mongolia, have mostly considered this history as an ideological object, i.e. in the theoretical framework of historical materialism, the theory of socio-economic formation. It is therefore now necessary to analyse critically Mongolian historiography and to free Mongolian history from this ideological scheme. In doing this, however, one should not let ones approach be influenced by the present euphoria of radical change or by short-lived political ideas. Rather, it is necessary to apply cognitive norms of analysis to the real historical facts.

Except for very few treatises, there have been hitherto no investigations into this problem. The present work is an attempt to evaluate the course of Mongolian history over a relatively broad period with regard to the structural and developmental characteristics of Mongolian nomadic society. To achieve this, it is necessary to analyse the subject matter from both a theoretical and an empirical perspective. In order to systematise the course of Mongolian history and the available sources and secondary material, we have considered it appropriate to restrict our attention to the period from the twelfth century to the nineteenth century. The following significant facts have guided us in this decision: (a) it was only at the end of the twelfth century that an independent and stable Mongolian social system developed, and (b) with the Manchurian conquest and the growth of Buddhism, the spontaneous development of Mongolia ceased some time about the eighteenth century to evolve according to the predominantly internal dynamics of traditional nomadic society; the long chain of traditional, spontaneously developing nomadic societies thereby ended.