A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

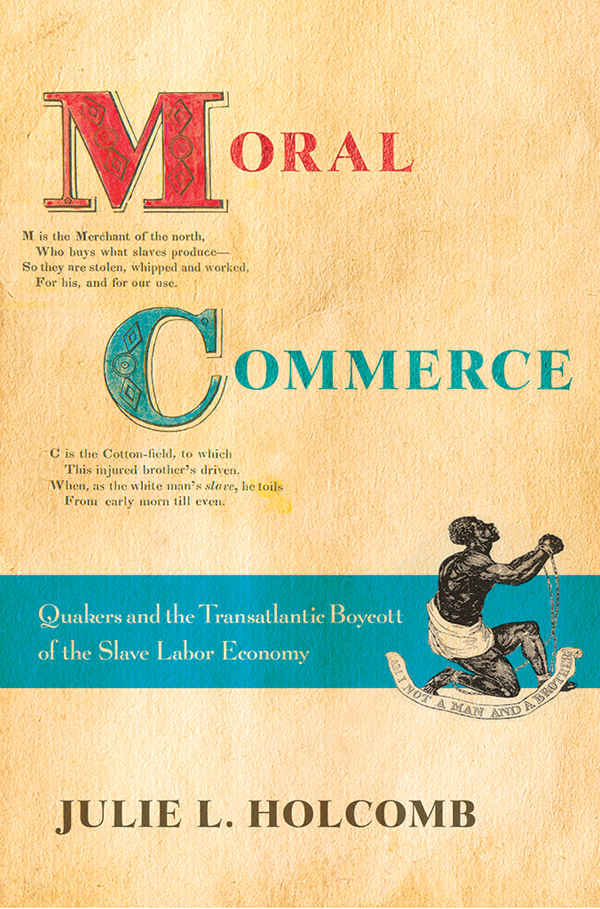

As a history major at Pacific University, I anticipated a career that would combine my interests in public and academic history with a desire to study American labor history, particularly the activism of women like the Progressive Era labor reformer Florence Kelley. Although my intellectual interests have changed in the last fifteen years, I have, in many ways, come full circle because it was in writing about Kelley, the niece of Quaker free-produce activist and abolitionist Sarah Pugh, that I first encountered the American free-produce movement. Pugh and the other activists who boycotted slave-labor goods have engaged my deepest intellectual interests for more than ten years. In researching and writing the story of the boycott of slave labor, I have had the opportunity to work with many individuals and institutions. It is a pleasure to acknowledge the many ways in which they have supported and shaped this work.

This book began as a research project under the direction of Sam W. Haynes at the University of Texas at Arlington. He along with Stephanie Cole helped shepherd me through both the exam and the dissertation process. Their generous feedback and their critical reading of my research helped clarify my ideas, and their influence remains although the book bears little resemblance to that research. I also benefited from the knowledge and advice of several other historians at UTA, including Robert Fairbanks, Stephen Maizlish, Christopher Morris, and Steven Reinhardt.

At Cornell University Press, Michael McGandy worked hard to help me to transform an academic document into a book. I appreciate his support and his patience as well as the assistance of the various editors, especially my copy editor, and staff members who helped bring this project through to publication. I also thank Richard Huzzey and Beth Salerno for their incisive comments on various drafts of the manuscript. Their suggestions, comments, and questions have made this a much better work.

I appreciate the many scholars who have commented on conference papers and chapter drafts, including Winifred Connerton, A. Glenn Crothers, Seymour Drescher, Carol Faulkner, Lynne Getz, Natalie Joy, Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz, Bruce Laurie, Seth Offenbach, Stacey Robertson, Srividhya Swaminathan, Julie Turner, and Michael Woods. I also thank Caleb McDaniel, Edward Rugemer, and Beverly Tomek.

For the past eight years, Baylor University has been my academic home. In the department of museum studies and in the larger university community I have found a supportive, collegial group of colleagues, including Eric Ames, Ellie Caston, Trey Crumpton, Kenneth Hafertepe, Heidi Hornick, T. Michael Parrish, Stephen Sloan, Gary Smith, Joy Summar-Smith, Stephanie Turnham, and Lenore Wright. Lisa Rieger, administrative associate for the department of museum studies, has assisted in ways both large and small as has the amazing staff of the Mayborn Museum Complex. I am indeed quite fortunate to work with such a generous and talented group of people.

The knowledge, skills, and guidance of numerous archivists and librarians were invaluable to this project. I relied in particular on the amazing Quaker collections at Swarthmore and Haverford Colleges. At Swarthmore, Christopher Densmore, director of the Friends Historical Library, along with Patricia ODonnell and Susanna Morikawa, provided valuable assistance and advice. At Haverford, I thank Sarah Horowitz, head of special collections, as well as past staff members, Diana Franzusoff Peterson and Ann Upton. I am grateful to the staff members of the Chester County Historical Society and the Boston Public Library. At Baylor University and at the University of Texas at Arlington, the staff members of the interlibrary loan departments were remarkably intrepid, tracking down even the most obscure of sources.

The Office of the Vice Provost for Research at Baylor University supported this project with grants from the University Research Committee and the Arts and Humanities Research Program. Financial support came also from the American Historical Association in the form of an Albert J. Beveridge grant. As a doctoral student, I received funding from the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in Texas, Ft. Worth Town Chapter; the Trudy and Ben Termini Graduate Student Research Grant fund; and the history department, University of Texas at Arlington.

No project of this magnitude happens without the support of friends and family. For more than fifteen years, my life has been enriched by the friendship of Sarah Canby Jackson. I also thank Mary Hayes, Michael and Alice Mattick, Rosalie Meier, Amanda Morrison, Sue Sanders, and Hugh and Bonnie Reynolds. At St. Joseph Catholic Church, I have found a warm, welcoming community of friends who have sustained me. Their friendship and their faith is a much needed reprieve from teaching, research, and writing. I know that I could not have finished this project without the support of my extended family: Mark Holcomb and Sara Eckel, David Holcomb, Steven and Debra Holcomb, as well as my son-in-law Eric Sfetku and his parents Bob and Joyce Sfetku. My daughter Jennifer Holcomb Sfetku has been an amazing force for good in my life. She continues to inspire me. My grandchildren Noah and Paige remind me that my most important title, my most important role is to be their Grams. I hope Noah will not be too disappointed that the cover does not say Grams Holcomb.

More than anyone, my husband Stan Holcomb has felt the stress of this particular project, which has occupied me for a full one-third of our time as husband and wife. For more than thirty years, his unwavering, unconditional love has kept me centered. Words cannot sufficiently express my appreciation for his laughter, his faith, his patience, and his reassurance throughout this process. Only he can understand what I mean when I say this book is, like its author, his.

Introduction

A Principle Both Moral and Commercial

To live means to buy, to buy means to have power, to have power means to have responsibility.

Florence Kelley, Founder, National Consumers League, c. 1914

In May 1840, New York businessmen Thomas McClintock and Richard P. Hunt presented American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison with four yards of olive wool suiting that had been manufactured at Hunts Waterloo woolen mill. The gift to the publisher of the Liberator was intended to publicize the free-produce cause. McClintock and Hunt were antislavery Quakers who boycotted the products of slave labor: McClintock helped establish the Free Produce Society of Pennsylvania, while Hunt chose to manufacture free-labor wool rather than slave-grown cotton.

Like many abolitionists in the 1820s and 1830s, Garrison supported free produce, describing it as the most comprehensive mode that can be adopted to destroy the growth of slavery. Although he did not believe the boycott should be the sole weapon in the fight against slavery, Garrison did call for the multiplication of free produce societies.

Throughout the late 1830s and 1840s, McClintock, Hunt, and other supporters of the boycott tried in vain to change Garrisons mind. Among those supporters was Sarah Pugh, a Philadelphia Quaker and an officer of the American Free Produce Association (AFPA). A petite woman, she was characterized as conscience incarnate by her niece, the Progressive Era labor reformer Florence Kelley. Pugh joined the abolitionist movement in 1835, after hearing a speech by British abolitionist George Thompson. A member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) as well as the AFPA, Pugh represented both organizations at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840. She lamented abolitionists apathy toward the boycott of slave labor: The great mass of abolitionists need an abstinence baptism. In a direct reference to Garrisons dismissal of free produce, she claimed many abolitionists had sacrificed political party and religious sect for the cause of freedom, yet the taint of slavery still clings to them, and they need to be pointed to the stain that dims their otherwise consistent testimony. Pugh emphasized both the economic principle and the moral commitment of free produce. Although she recognized the practical limits of the boycott of slave labor, she still believed it possible for abolitionists to cease from